Chaucer and the astrolabe (I)

Chaucer and the astrolabe (I)

Geoffrey Chaucer (c1340 – 1400) was England’s major medieval poet and, as one of the most illustrious figures in English literature, well deserves his prior place in Poet’s Corner. Best known for his Canterbury Tales, Chaucer also wrote the scientific text Treatise on the Astrolabe, and (possibly) a book of astronomical tables, Equatorie of the Planetis. The Treatise, though partly translated from an earlier Latin version of an Arabic text, is a model of clarity. It is easily understood even today, despite a few factual errors of detail.

The astrolabe was the most important scientific instrument for astronomers, astrologers and surveyors until the late 17th century. It was probably developed in ancient Alexandria by the astronomer Hipparchus around 150 B.C., and is a very versatile device. It can be used to find stellar and solar time, times of sunrise and sunset, the positions of the sun, moon, stars and planets, and the heights of objects. Chaucer’s Treatise on the astrolabe became a standard source for astronomers and surveyors in the English speaking world. Thus Chaucer made a small but significant contribution to the world of mathematics.

Project Find out how to construct and use an astrolabe. See, e.g., ‘The Astrolabe’, by J.D. North in Scientific American, Jan. 1974, 96 – 106.

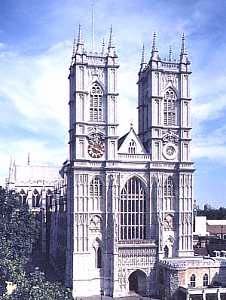

Poets’ corner

Poets’ corner Chaucer and the astrolabe (I)

Chaucer and the astrolabe (I) Chaucer and mathematics

Chaucer and mathematics The Poets’ salute to Newton and other mathematicians

The Poets’ salute to Newton and other mathematicians :

: