A. EXTERIOR

To reach the Cathedral from Edinburgh Waverley Railway Station, we exit the central concourse south to Market Street. Walking west brings us to Cockburn Street on our right, and then a steep climb up the steps of Warriston Close brings us out at St Giles. We begin our exploration at the west end of the Cathedral where there is a large open square, and a prominent statue of Walter Francis Scott (not the famous author). Car parking is available a little way to the east of the Cathedral, but it is probably not a good idea! INDEX

A2. WEST WALL GA

Some of the most decorative external features of the Cathedral are the central tower and crown, and the various ornate porticoes around the entrances. However, there are other pleasing features such as the little oriel window seen here to the right.

A3. ORIEL WINDOW TWB GA

We shall look more closely at the oriel window from inside shortly, but the window was erected by the High Constables and Guard of Honour of Holyroodhouse in 1883. We can see here the outline of a unicorn, symbol of Scotland.

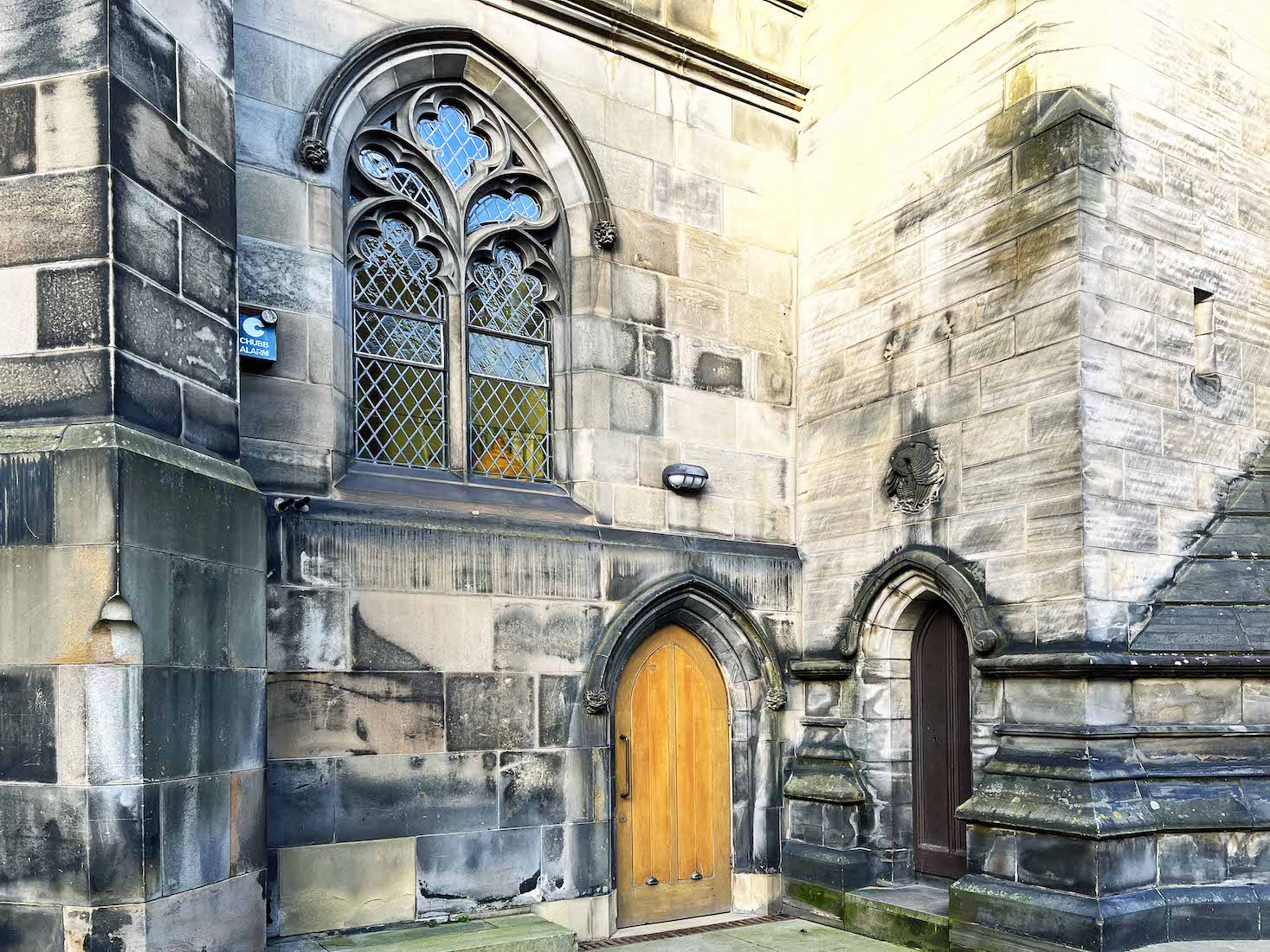

A4. SOUTHWEST CORNER TWB TWB

Following around the South side of the Cathedral we come to various small doors and windows. The locally quarried stone has beautiful gradations of colour. There is a private access through to the interior Moray Aisle through this door.

A5. CHARLES II STATUE GM

Near the South transept, this life-sized statue of Charles II was erected in 1685, the year of the king’s death. It’s believed to be the oldest lead equestrian statue in the United Kingdom, and is the oldest statue in Edinburgh. Charles II is depicted donning Roman military garb, wielding a baton meant to symbolize Imperial authority. [Photo Credit: Street View]

A6. CROWN GA

St Giles' crown steeple is one of Edinburgh's most famous and distinctive landmarks. Cameron Lees wrote of the steeple: ‘Edinburgh would not be Edinburgh without it.’ The crown steeple has been dated to between 1460 and 1467. The steeple is one of two surviving medieval crown steeples in Scotland: the other is at King's College, Aberdeen and dates from after 1505. The weathercock atop the central pinnacle was created by Alexander Anderson in 1667; it replaced an earlier weathercock of 1567 by Alexander Honeyman.

A7. TOWER AND CROWN GA GA

The tower contains three bells. The Great Bell is believed to have come from Guelderland, a fertile province in The Netherlands. It was cast by John and William Hoehren in 1460. James II was King of Scots at that time, and his Queen, Mary of Gueldres, may well have suggested the commission. However, it had to be re-cast by C. and G. Mears in London in 1846. It used to toll to summon people to services and to mark important occasions, but although it does not now do that, it rings the hours every day. There are also two small bells which ring the quarter hours. One was made in 1706 and the other in 1728, both by Robert Maxwell.

A8. SOUTH SIDE DOORS TWB

We continue our walk around the Cathedral. Just East of the South transept there is a lower extension with two doors leading to non-public spaces. Every cathedral has its secrets!

A9. THISTLE CHAPEL GM

This brings us to the Thistle Chapel – the chapel of the Order of the Thistle. At the foundation of the Order of the Thistle in 1687, James VII ordered Holyrood Abbey be fitted out as a chapel for the Knights. At James’ deposition the following year, a mob destroyed the Chapel’s interior before the Knights ever met there. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, multiple proposals were made either to refurbish Holyrood Abbey for the Order of the Thistle, or to create a chapel within St Giles’ Cathedral. In 1906, after the sons of Ronald Leslie-Melville, 11th Earl of Leven donated £24,000 from their late father's estate, Edward VII ordered a new Chapel to be constructed on the South side of St Giles’. The Chapel was built and opened in 1911. [Photo Credit: Street View]

A10. DETAILS OF THE THISTLE CHAPEL TWB TWB

In the building of the Chapel, there was a great emphasis on fine craftsmanship, and this can be seen both in the interior and exterior fashioning of the Chapel.

A11. EAST ENTRY TWB

Walking around the Thistle Chapel to the East face, we arrive at the East portal. This is less decorated than the West portal, but nevertheless has its share of interesting nationalistic and ecclesiastical carvings. In the strip above the door, the central figure appears to be an angel holding a shield. At left is a shield with the St Andrew's cross, various thistles and a fleur-de-lys. At right is a shield with the cross of St George, more thistles, and two English (Scottish?) roses.

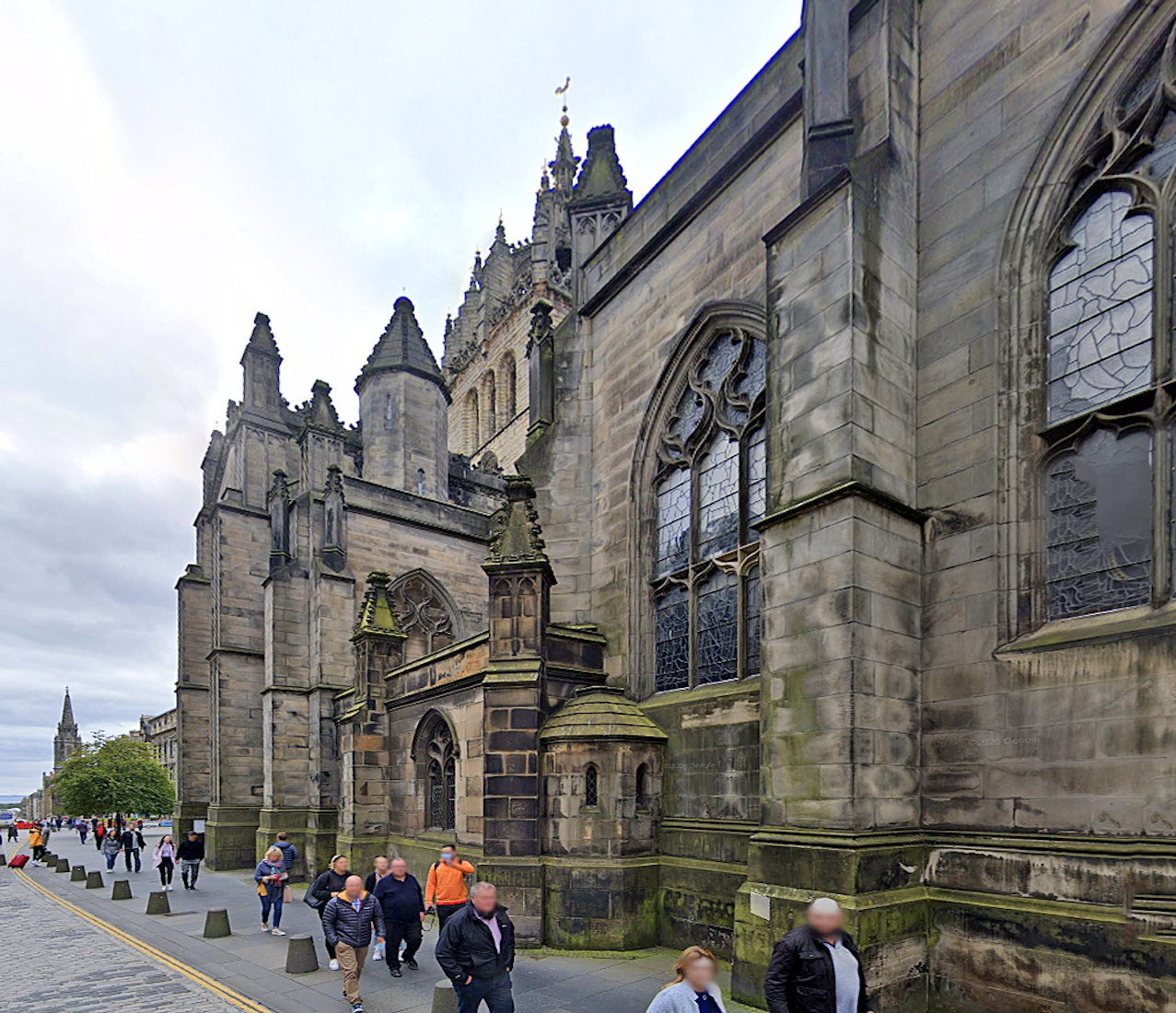

A12. NORTHEAST VIEW Geograph

Further round there are imposing views of the East wall with its three large stained glass windows. In the foreground is a substantial structure, rather strangely called the Mercat Cross. In fact, a mercat cross is the Scots name for the market cross found frequently in Scottish cities, towns and villages where historically the right to hold a regular market or fair was granted by the monarch, a bishop or a baron. [Photo Credit: Geograph – Alan Findlay]

A13. MERCAT(OR) CROSS GA GA

The current mercat cross in Edinburgh is of Victorian origin, but was built close to the site occupied by the original. It has a long involved history! Around the top are various brightly coloured medallions. The central tower supports a unicorn. Using heraldry as a guide we find that the unicorn was first introduced to the royal arms of Scotland around the mid-1500s. Prior to the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the Scottish coat-of-arms was supported by two unicorns. However, when King James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, he replaced one of the unicorns with the national animal of England, the lion, as a display of unity between the two countries. Apparently folklore fans know that lions and unicorns have always been enemies, locked in a battle for the title of ‘king of the beasts’!

A14. SHOP GM

We continue our walk back alongside the North wall of the Cathedral, first passing the shop. [Photo Credit: Street View]

A15. NORTH TRANSEPT GM

Soon the North transept towers above us. We look forward to viewing these large stained glass windows from the inside. [Photo Credit: Street View]

A16. NORTH WALL GM

We observe that there is an entry portal beneath the main window of the North transept. To the right of the transept is another of those intriguing Cathedral side extensions, this one accessible by a (locked) door in the nave. [Photo Credit: Adrian Candela]

A17. CONTINUING OUR CIRCUIT GM

A better view of the North side ... . [Photo Credit: Street View]

A18. NORTHWEST CORNER GM

We notice that the walls are supported by solid vertical buttresses, each topped by a small roofed square tower. A smaller angled roofed square tower in front of each is a nice design feature. [Photo Credit: Guido Galle]

A19. WALTER FRANCIS SCOTT MEMORIAL LM

The regal bronze cast of a standing figure wearing Order of the Garter robe depicts Walter Francis Montagu Douglas Scott, 5th Duke of Buccleuch and 7th Duke of Queensberry. He is no relation to the noted author Sir Walter Scott, who is commemorated by a large monument in Princes Street on the other side of town.

A20. WEST WALL LM

The exterior of the Cathedral, with the exception of the tower, dates almost entirely from William Burn’s restoration of 1829-33 and afterwards. Burn created a symmetrical western façade by replacing the west window of the Albany Aisle at the northwest corner of the church with a double niche and by moving the west window of the inner south nave aisle to repeat this arrangement in the southern half. The elaborate West doorway dates from the Victorian restoration and is by William Hay.