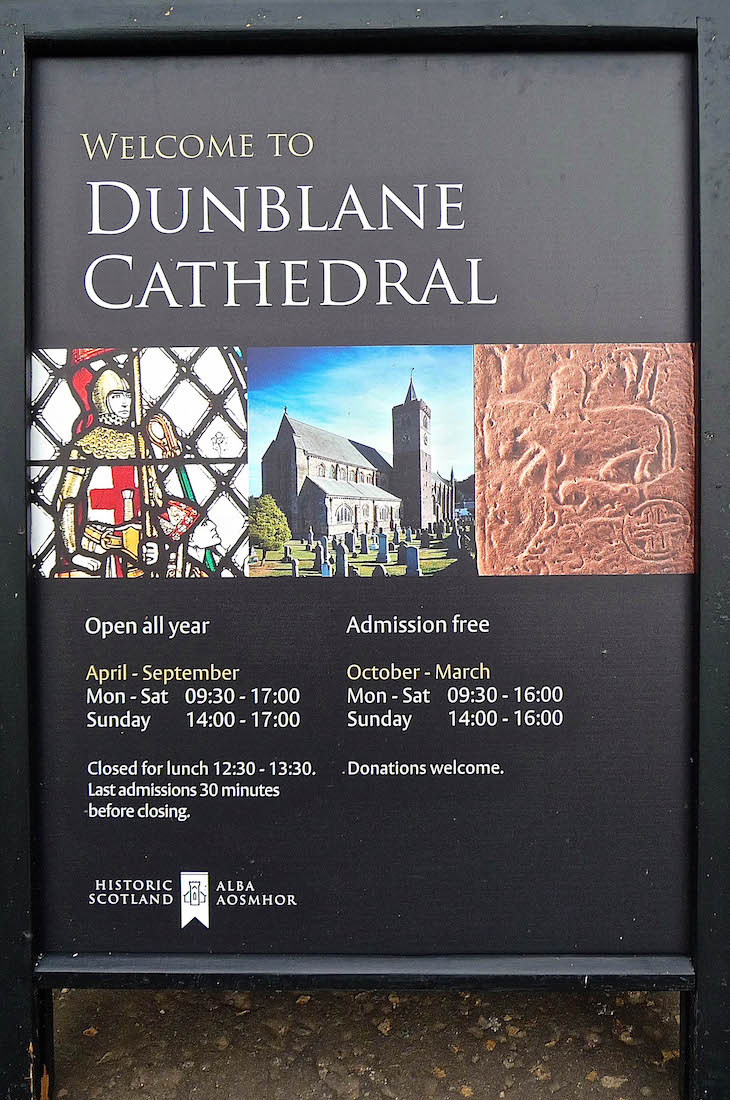

From the Dunblane township we walk up High Street and along The Cross, and here we are! The grand old Dunblane Cathedral with its leaning tower ... . The name Dunblane (meadow of Blane) probably comes from the site’s use by monks from St Blane’s on the Isle of Bute. They may have fled the Isle of Bute with their saint’s relics to escape Viking raids.

2. SOUTHEAST VIEW GA

In our usual way, we shall begin our exploration by walking around the outside of the Cathedral. It is clear that the tower intrudes into the Southern nave aisle. On this side of the tower is a main entrance, and next to it an attempt at creating a South transept? And at right, six large stained glass windows in the Choir.

3. TOWER GA

It is clear that the tower has been added to, with different building materials for the top two stories, and a change to Gothic style in the windows. The additions were made about 1500 –- on the parapet are the arms of Bishop Chisholm. The tower houses nine change-ringing bells. The largest is E-flat and weighs 24 hundred-weight. The clock chimes the Alleluia quarters.

4. CHOIR WALL JG

The East end is the choir and sanctuary. The six tall Gothic windows alternate with buttresses which terminate with small pinnacles at the roof line.

5. EAST WALL GA

From the East, the striking East window is flanked by two little capped towers, and above is a cross which has seen better days!

6. HEADSTONES JG

All around the Cathedral is a green lawned churchyard with many headstones. There are two war graves here, including that of William Stirling, a gunner in the Royal Marine Artillery during World War I.

7. NORTH WALL GA

Most cathedrals seem to have a ‘good’ side which is much photographed, and a less interesting side. This is the North wall as seen from Haining (Street). At left is the chapter house with five sets of main windows, and is that a chimney? Another mini-transept marks the transition to the nave. Although the Cathedral was built over a long period, there is a pleasing uniformity in the window styling and use of building materials.

8. NORTHWEST VIEW GA

Perhaps we spoke too soon! Moving to the West end we notice a sudden change in the lower nave window styling. As well, there is now a variation in the style of the upper clerestory windows. Hiding behind the shrubbery here is a door through to the North aisle.

9. NORTH AISLE DOOR GA

This door is obviously not much used. The top stonework looks as though it may have been part of some larger structure.

10. WEST WALL AND DOOR GA

So to the West wall. The West door sits within nested Gothic arches, and there is an old empty niche on either side. The yellow freestone from which the Cathedral is built has attractive traces of colour.

11. SOUTHWEST VIEW W:NA

We observe that the high window in the gable of this wall is not circular, but rather more of a ‘pointed ellipse’ or mandorla. It is not visible from inside the Cathedral. [Credit: CCL Wikimedia : Neil Aitkenhead]

12. SOUTH WALL GA

We return to our starting point. Time now to enter the Cathedral ... .

14. ENTRY DOOR JG

... but not for long! We make our way inside, and walk back to the West wall of the nave.

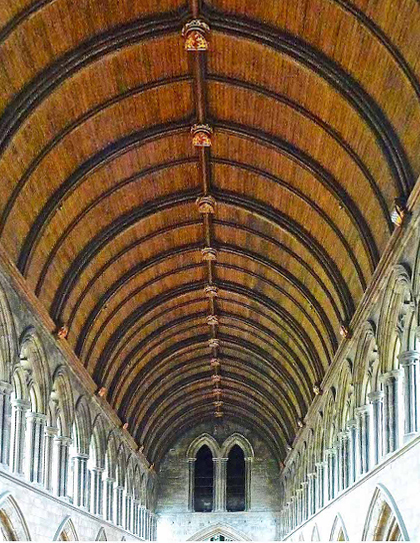

15. NAVE JG GA

I always enjoy this view of a church or cathedral. To the sides the multi-straw Gothic columns march down towards the choir screen. Pulpit, lectern and organ are visible in the distance. And in the foreground we may be able to see some decoration on the top of the pew ends. • Above us is an unusual barrel roof. The bosses show the coats of arms of the feudal patrons of the Cathedral, and also reflect the Cathedral’s history. And hidden away, just visible, at the end of the nave above the two little Gothic arches, are the arms of Queen Victoria.

16. NAVE SEATING, COLUMN AND PEW END JG JG SC

We can obtain an elevated view of the nave by climbing the spiral stairs to the walkway in front of the West window. The nave is quite long. In fact it measures internally 129 feet (39.3m) in length by 57 feet (17.4m) in width (including the aisles), and is divided into eight bays. And the pew ends are indeed beautifully decorated.

17. NAVE LOOKING WEST GA

Looking back towards the West wall of the nave, we can see the West window with a small gallery below, and at floor level, two historic sets of choir stalls, one on each side of the entry porch. The clerestory windows above the arches give good lighting to the Cathedral.

18. GREAT WEST WINDOW GA

The Great West Window portrays the tree of Jesse. It was executed by Clayton and Bell of London in 1906, a gift of Sir Robert Younger (later Lord Blanesburgh) as a tribute to his parents. The Tree of Jesse, a favourite theme in medieval art, is a reminder of the incarnation, that the Son of God actually became man, the Son of David. Jesse reclines at the bottom left of the central light at the root of a tree growing upwards through David and Solomon and many others.

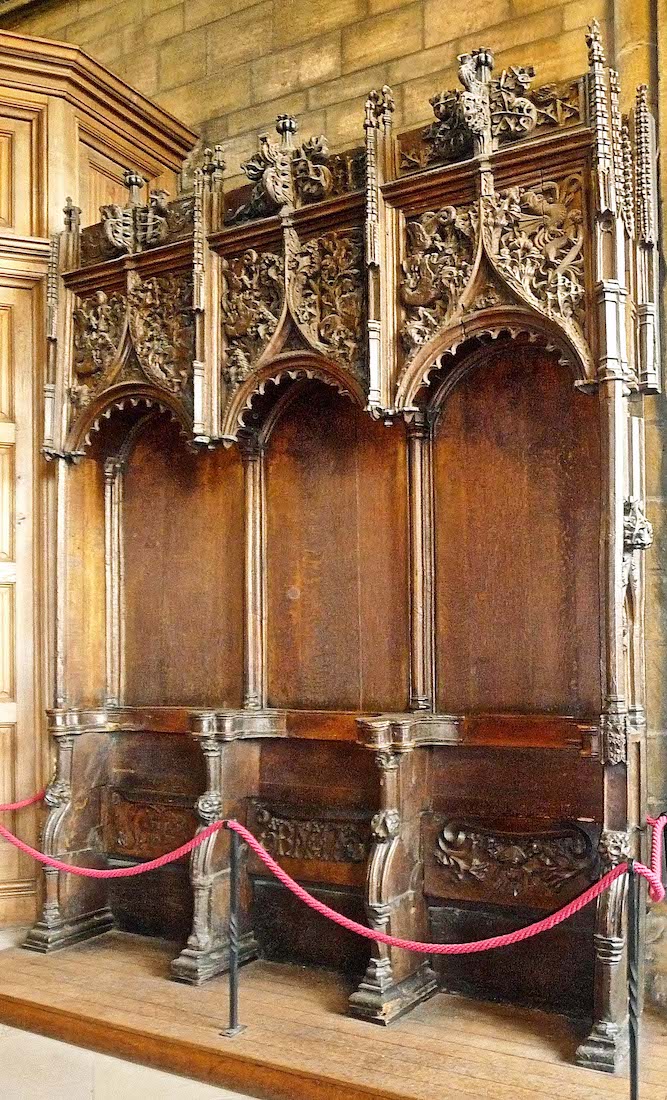

19. WESTERN STALLS GA GA

These ornate stalls come from the Cathedral choir. In Scotland, 15th-century stalls of this kind are very rare, as many were removed during the Protestant Reformation

20. CANOPIES AND MISERICORDS GA

The stalls haveGothic style canopies with carved floral and fruit motifs. There are also carved misericords under the seats. These are small structures that offer support to a person standing or kneeling in prayer. One of the seats has a carving of a bishop’s mitre. You can find some details of these misericords here.