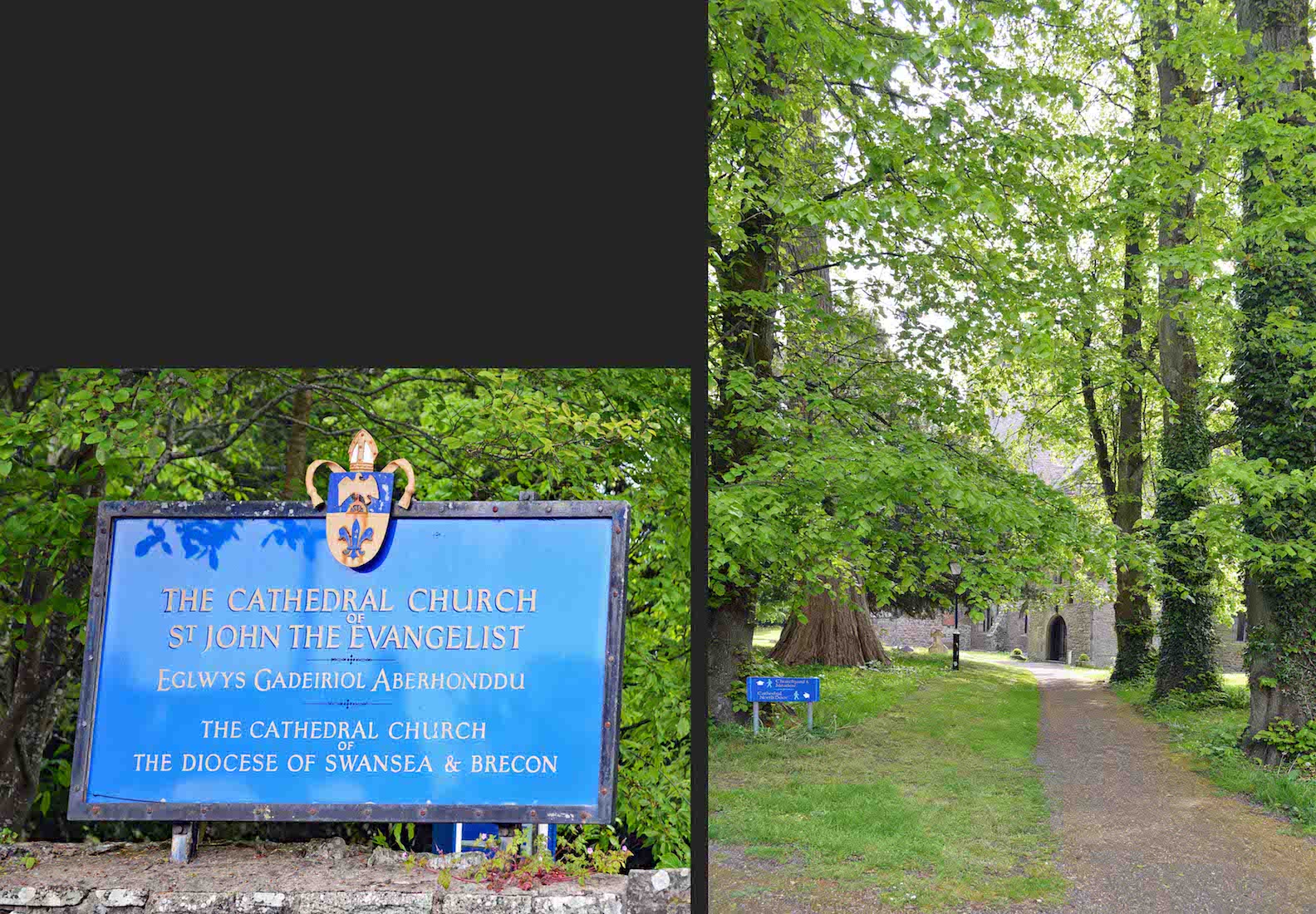

Brecon in Powys is a market town, some one hour’s drive north of Cardiff. The name is associated with Brecon Beacon’s National Park, but Brecon is also the location of Brecon Cathedral, the Cathedral Church of St John the Evangelist. This is the cathedral of the Diocese of Swansea and Brecon in the Church in Wales and seat of the Bishop of Swansea and Brecon. ••• We walk up the hill from the town, coming to this attractive lychgate.

2. TO THE NORTH DOOR

Previously the church of Brecon Priory and then the Parish Church of St John the Evangelist, it became Brecon Cathedral following the disestablishment of the Church in Wales in 1920 and the creation of the diocese in 1923. ••• Passing the Welcome sign, there is a path to the right leading to the North Porch. However, we continue straight ahead to achieve our goal of walking right around the Cathedral.

3. CHURCHYARD

The Cathedral is set in beautiful green parkland, and to our left is the churchyard with many graves. Charles Lumley (1824–1858), awarded the Victoria Cross during the Crimean War, was buried here. ••• Because of the characteristic round shape of its grounds, the Cathedral is thought to be on the site of an earlier Celtic church, of which no trace remains.

4. GLIMPSE OF THE CATHEDRAL

A well formed path leads us alongside the North wall of the Cathedral. ••• In 1093 a new church, dedicated to St. John, was built on the orders of Bernard de Neufmarché, the Norman knight who conquered the kingdom of Brycheiniog. He gave the church to one of his followers, Roger, a monk from Battle Abbey, who founded a priory on the site as a daughter house of Battle.

5. HAVARD CHAPEL

At the East end of the Cathedral is this substantial chapel – the Havard Chapel. ••• The first prior at Brecon was Walter, another monk from Battle. Bernard de Neufmarché also endowed the priory with lands, rights and tithes from the surrounding area, and, after his death, it passed to the Earls of Hereford, so giving it greater prosperity.

6. EAST WALL AND TOWER

We now find that our path leads us away from the Cathedral with a large hedge blocking access. ••• The church was rebuilt and extended in the Gothic style in about 1215, during the reign of King John. In the Middle Ages, the church was known as the church of Holy Rood or Holy Cross, because it owned a great ‘golden rood’ which was an object of pilgrimage and veneration until it was destroyed in the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century.

7. AROUND PAST THE TEA ROOMS

We retrace our steps to the paved area back beyond the lychgate, and follow this path to the right (our left) around the West end of the Cathedral. ••• In 1538 the Prior was pensioned off, and the priory church became the parish church. Some of the surrounding buildings were adapted for secular use; and others, such as the cloisters, were left to decay and were later demolished.

8. SOUTH SIDE

In recent years, some of the buildings in the cathedral close have been converted into a diocesan centre, a heritage centre and exhibition, as well as a shop and “Pilgrims’ Tea Rooms”. Following the path past this café and around these buildings, we come to a pleasant lawned area fronting the South side of the Cathedral.

In recent years, some of the buildings in the cathedral close have been converted into a diocesan centre, a heritage centre and exhibition, as well as a shop and “Pilgrims’ Tea Rooms”. Following the path past this café and around these buildings, we come to a pleasant lawned area fronting the South side of the Cathedral.

9. SOUTHEAST CORNER

There is a wonderful tree at the Southeast corner of the Cathedral, although it has been sadly lopped. ••• By the 19th century, the church was in poor repair and only the nave was in use. Some restoration took place in 1836, but major renovation of the church did not start until the 1860s. The tower was strengthened in 1914. The cathedral is a Grade I listed building.

10. EAST WALL AGAIN

We have now come back to the East wall, and have viewed all sides of the Cathedral. ••• In summary, Brecon Cathedral has been a site of Christian worship for nearly a thousand years. It became a cathedral in 1923, becoming the Cathedral Church of the newly formed Diocese of Swansea and Brecon. The Cathedral is set in a walled close, unique in Wales..

11. FOUNDATION STONE

Before we leave this area, we observe a foundation stone marked IHS 1929. This commemorates the rebuilding of the St Lawrence Chapel in 1929. ••• Brecon Cathedral has been described by Richard Haslam in the Pevsner Architectural Guide for Powys as ‘pre-eminently the most splendid and dignified Church in mid-Wales’. Definitely splendid and dignified!

12. TEA ROOMS OUTLOOK

Time now to enter into the Cathedral – there is an entrance at the Southwest corner opposite the tea rooms. Perhaps we should stop for a coffee first!

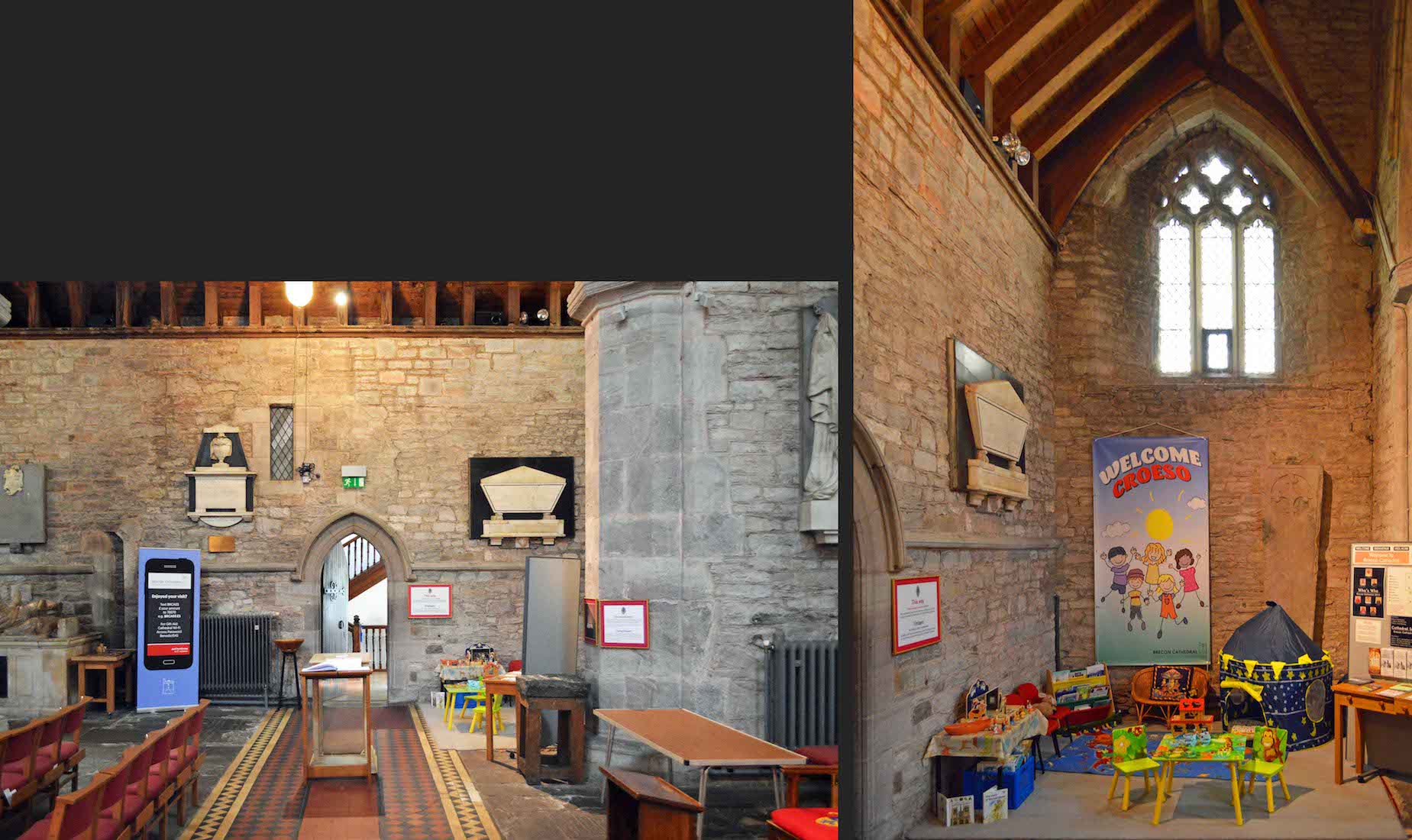

13. NAVE

My favourite view when coming to a new cathedral! The arches separate off the side aisles, and march towards the sanctuary. Here a chapel has been partitioned off at front left. All that survives of the original Norman Church is the font and some of the stonework in the walls at the east end of the nave. That Church was rebuilt in two different phases. Notice the different arches and windows on the North and South sides of the nave, or people’s part of the church. This part of the building was rebuilt about 1301 and the side chapels added by 1400.

14. NAVE ROOF

We look up to admire the fine timber roof of the nave which dates from the restoration by Sir Gilbert Scott in 1874-5. It reminds us of the upturned hull of a ship. The Latin word for ship is ‘navis’ and from that word derives our word ‘nave’ – the church building is like a ship, carrying the people of God.

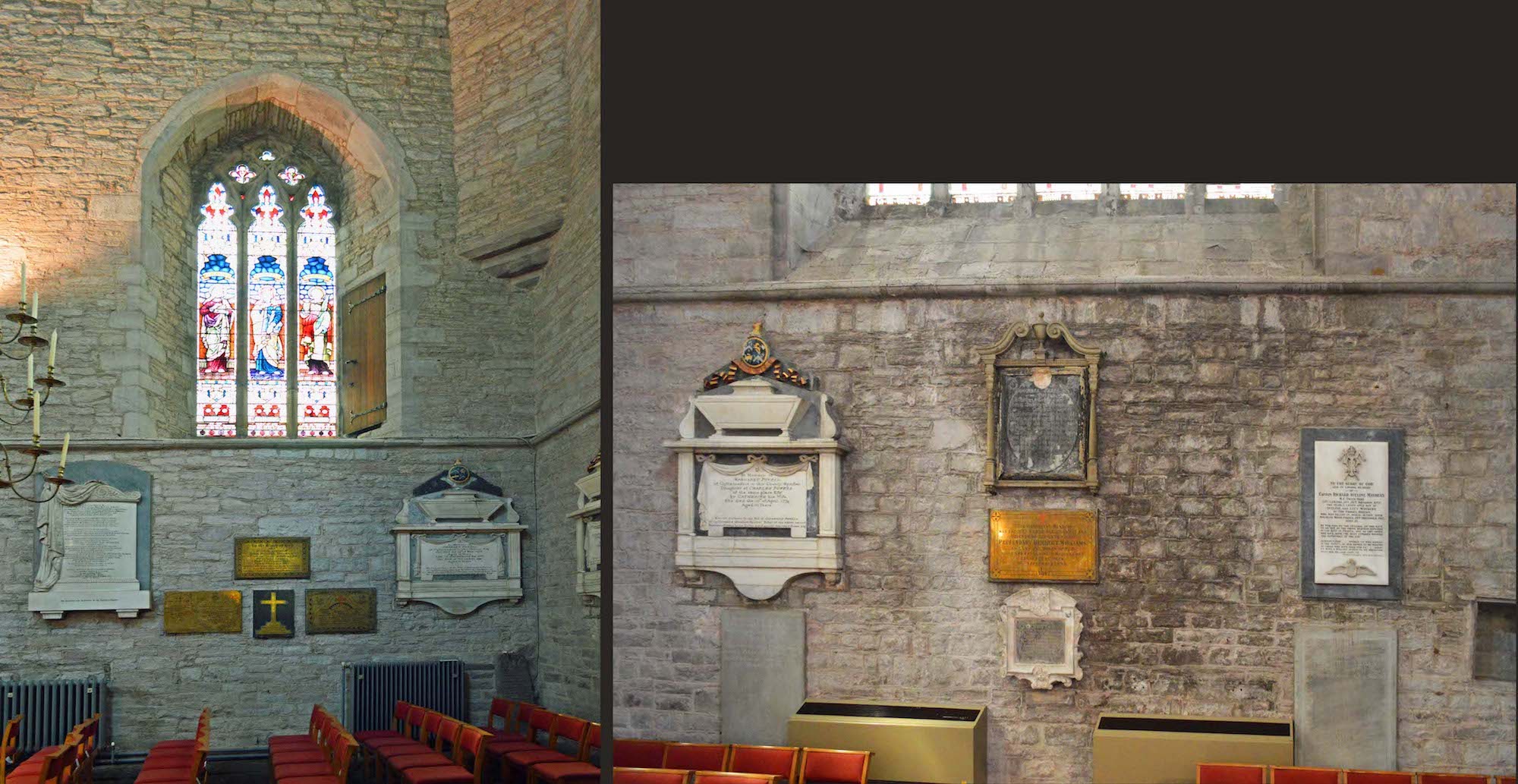

15. WEST NAVE

Looking closely at the West nave, we see that the central section is recessed back further than the end of the South (left) side aisle. This allows for two walls of plaques in the recess (South and West), and also a South facing window (the recess is just visible). In front of the Great West window is the baptismal font.

16. SOUTHWEST NAVE

We begin by looking at the Southwest corner. There is an entrance here – in fact leading from the Pilgrims’ Tea Rooms. To the right of this we obviously have an area set aside for children! The window is filled with clear lattice diamonds. Of more interest is the solid structure standing at the end of the partitioning wall.

17. CRESSET STONE

This remarkable cresset stone was found many years ago lying neglected in a garden in Pendre, Brecon, and was returned to the Priory Church at Brecon after restoration. There is evidence to show that it formerly belonged to the Priory Church, from where it was removed some sixty years ago. A ‘cresset stone’ was a flat stone with cup-shaped hollows, each being used to hold a quantity of tallow and a wick, which was burned to produce light. These were lit in the Church at midnight, when the monks came to mattins. This was a common method of lighting churches in medieval times. Although there are some thirteen cresset stones remaining in various parts of England, the Brecon cresset stone is the only one so far known in Wales, and is the finest yet discovered. It is rectangular in form, measures 23.5 inches x 21 inches, and is 6 inches thick. It has thirty cups arranged in five parallel rows, with six cups in each row.

18. THE CENTRAL WEST NAVE

Standing in the West recess, we view the two walls of memorials, and can see the South window with its very curious adjacent door (leading to ... ?). The gold plate tells that the West window was given by parishioners and friends of the late Prebendary Herbert Williams in 1898.

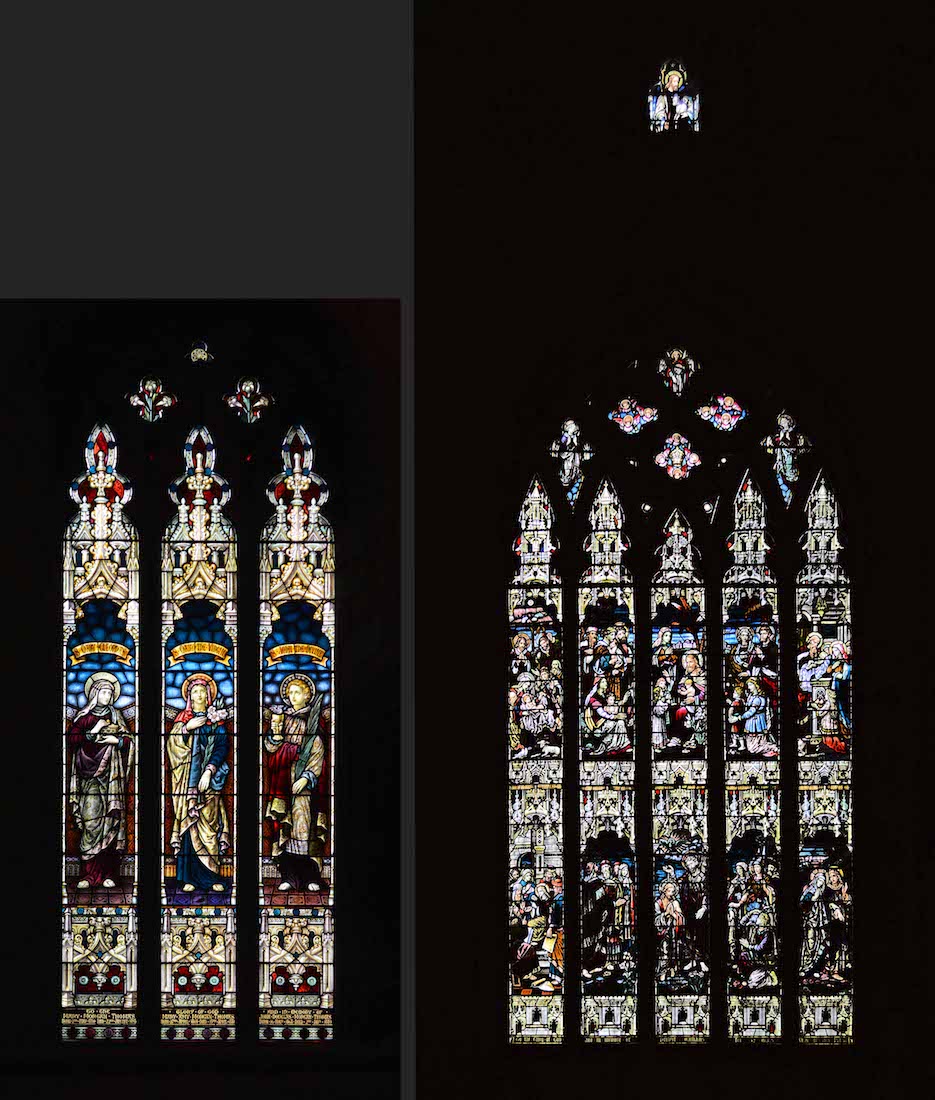

19. WEST WINDOWS

The side window at left shows St Mary Cleopas (Clopas), St Mary the Virgin, and St John the Divine. St Mary Clopas was present at the Crucifixion of Christ. The West window shows various scenes from the life of Christ including his dedication by Annas, his Baptism, teaching, and with the children.

20. BAPTISMAL FONT

The font is thought to be the oldest object in the Cathedral and it was probably made and carved for the Norman Church. It is adorned with grotesque marks, with fantastic birds and beasts intertwined. The designs on the bowl of the font deserve some explanation. We can make out a tree or bush, reminding us of the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden. There is a scorpion, a symbol of death, which Jesus conquered in His Resurrection, his rising from death. The eagle is the symbol of St John the Evangelist, Patron Saint of the Cathedral. The fish is one of the earliest Christian symbols, and also a sign of Baptism. Around the top of the bowl are the remnants of a Latin inscription referring to the Baptism of Jesus. From the way it has been carved, it is obvious that the stonemason knew very little good Latin!