It is worth spending a little time in the cloister. This is the Eastern walkway with the chapter house on our right, and leading to the Prior’s Door. This doorway was constructed in the late 12th century by Hugh Le Puiset, who added a similar one in Durham Castle. Notice too the colourful shields and bosses in the roof. PLAN

82. CATHEDRAL SHOP

A doorway leads from the Southwest corner of the cloister to the Cathedral’s very attractive and extensive shop. There is a great deal of material here relating to the Christian faith and to the Cathedral and its long history. The restaurant is behind us. Time for a coffee!

83. CHAPTER HOUSE

We return to look at the chapter house. This is, to a large extent, a reconstruction of the original, and dates from 1895. The original chapter house was partially demolished in 1796 because its large scale and high ceiling made it difficult to heat, and the 18th century clergy did not like it! The first Norman bishops are buried underneath the chapter house floor.

84. CHAPTER HOUSE WINDOWS

The main part of the chapter house has seven windows. These are modern and very interesting. Each window shows monks contemplating a heavenly ‘vision’. From left: Adam and Eve in the Garden, the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, Writing of the Gospels (St John : The Word became Flesh), the New Heaven and the New Earth.

85. FURTHER WINDOWS

There are four small windows in the chapter house facing the cloister. These are composite windows. The panel at left depicts the crucifixion, but the remaining windows are harder to interpret.

86. GALILEE CHAPEL

We return to the nave, and down some steps through the west wall to the Galilee Chapel. This chapel contains the tomb of the Venerable Bede (died 735 AD). Originally interred in Jarrow, his remains were stolen and brought here in 1022 in order to enhance Durham's collection of relics and, of course, attract more visitors!

87. CENTRAL ALTAR

The name Galilee was often used to designate the space at the Western end of a church, from which processions start their entry into the building, recalling Christ’s entry into Jerusalem from Galilee. There are three altars in this chapel. The central altar has a screen with a Crucifixion scene on it: this has been attributed to the Flemish painter Van Orley.

88. NORTHERN ALTAR

The Northermost altar in the Galilee Chapel has a plain wooden Cross behind it. Of particular interest are the fragments of wall painting above and behind it. The Galilee Chapel is one of the only places in the Cathedral where such murals remain. Much of the Cathedral would have been painted in this way – but the building was white-washed during the Reformation, and when the whitewash was removed during the Victorian era most of the murals were inadvertently scraped away as well.

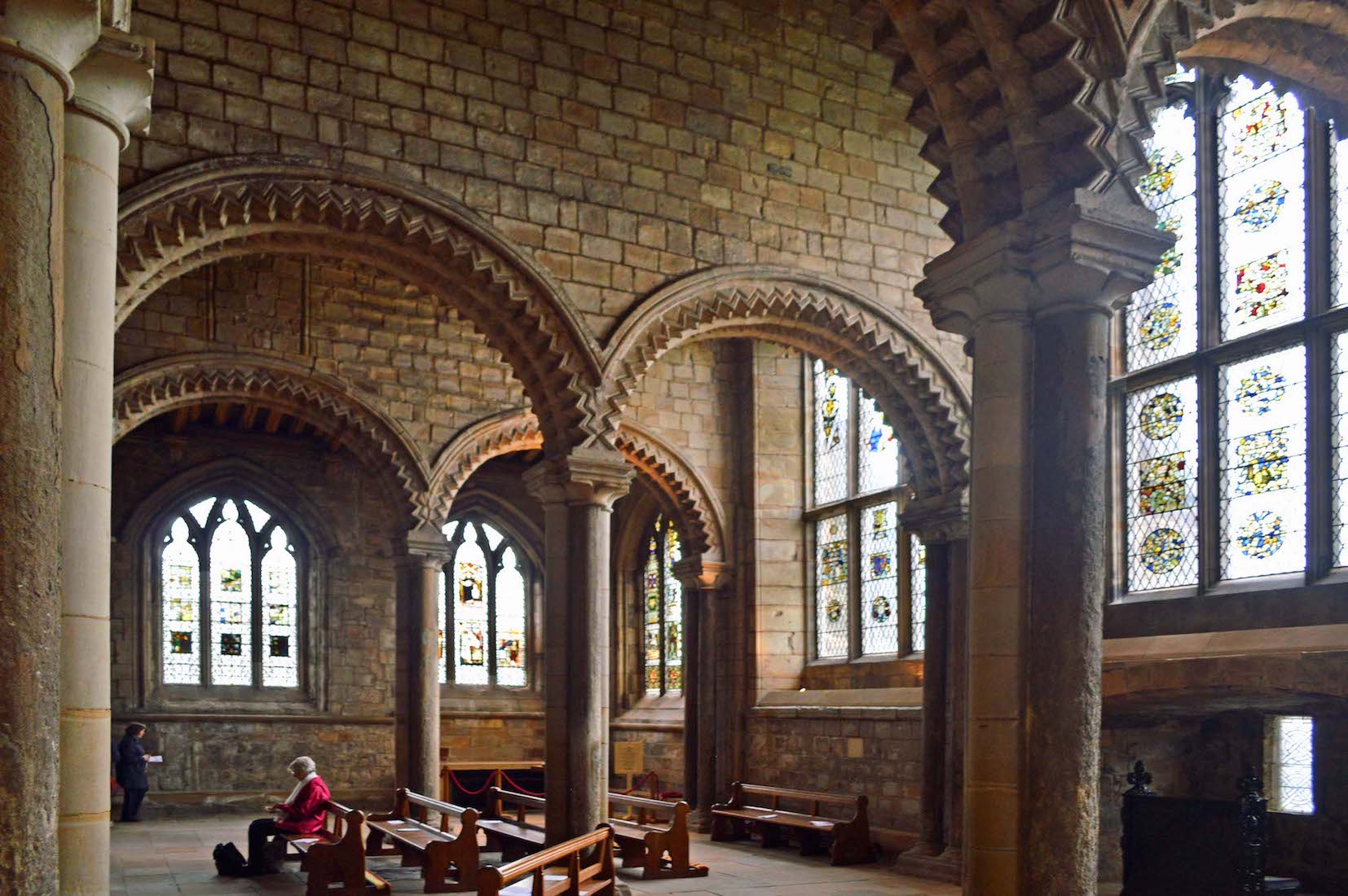

89. CHAPEL ARCHITECTURE

The graceful columns and arches of this Late Romanesque-Norman masterpiece are reminiscent of Moorish architecture, and the 12th century paintings on the east wall depict Saints Cuthbert and Oswald.

90. CHAPEL VIEW

This view looks to the Southwest of the Galilee Chapel. We particularly notice the windows and their placing for future reference. But also, there is a roped-off area in the corner ... where there is a primitive looking table.

91. LAST SUPPER TABLE

This sculpture was created 17 years ago during the time the sculptor was Artist in Residence at the Cathedral. It is made mostly from 500-year-old oak removed from the Cathedral tower during restoration work. When the table opens, you can see places set for the 12 disciples. The artist pictured Christ as the bottle of wine which sits in the centre of the table. The corners depict Matthew the lamb (?), Mark the lion, Luke the ox and John the eagle.

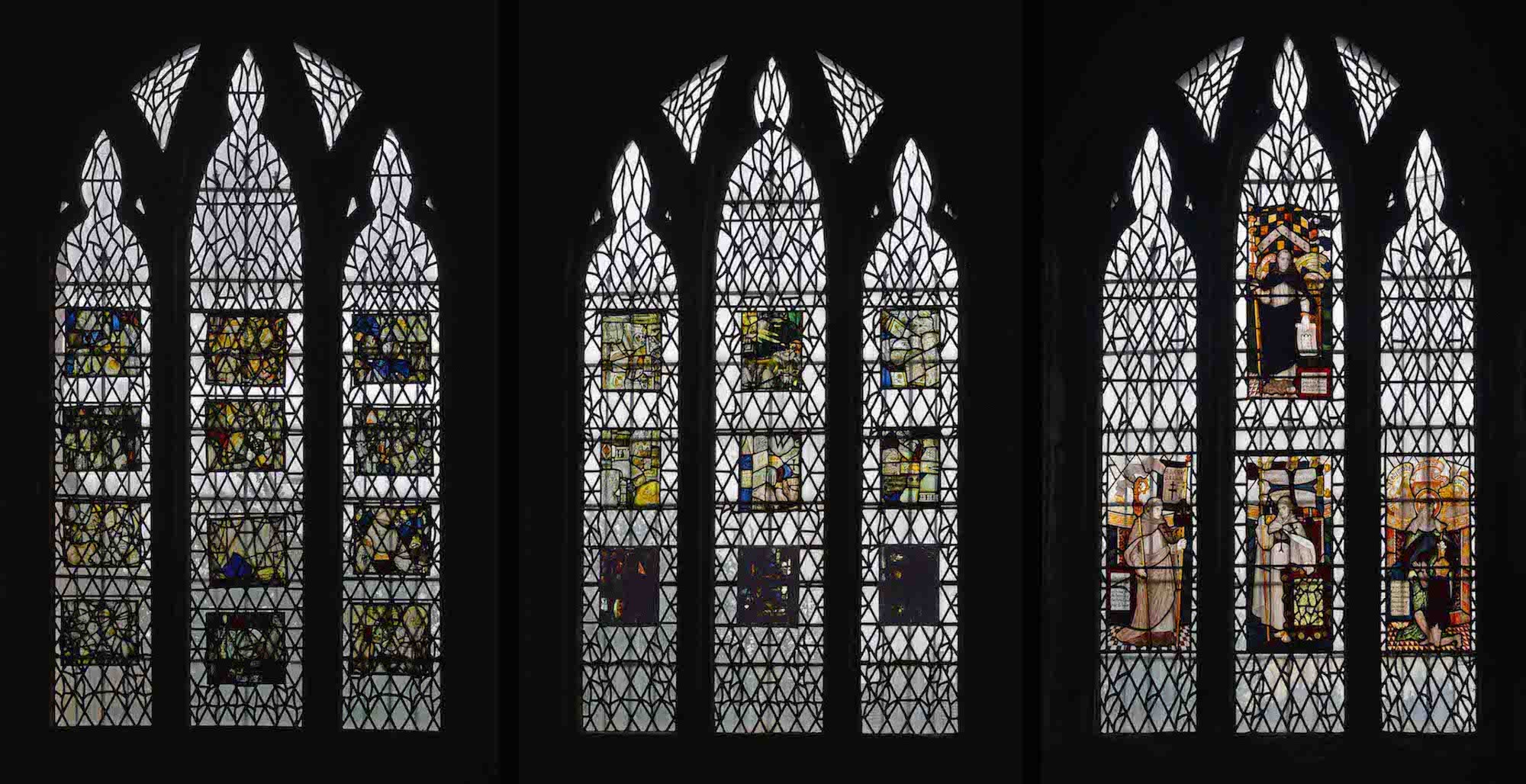

92. GALILEE WINDOWS: SOUTH WALL

The windows in the Galilee Chapel are composite, with old stained glass panels incorporated into clear-glass lattice windows. It is possible to identify certain figures and fragments, but more difficult to give any meaning.

93. GALILEE WINDOWS: WEST WALL

These five windows line the West wall of the chapel.

94. GALILEE WINDOWS: NORTH WALL

These three windows are found in the North wall of the chapel. The window at right is the Saints window. The two windows at left are modern. • We enjoyed a small service in the Galilee Chapel, but sadly I have to report that the Venerable Bede slept right though it!

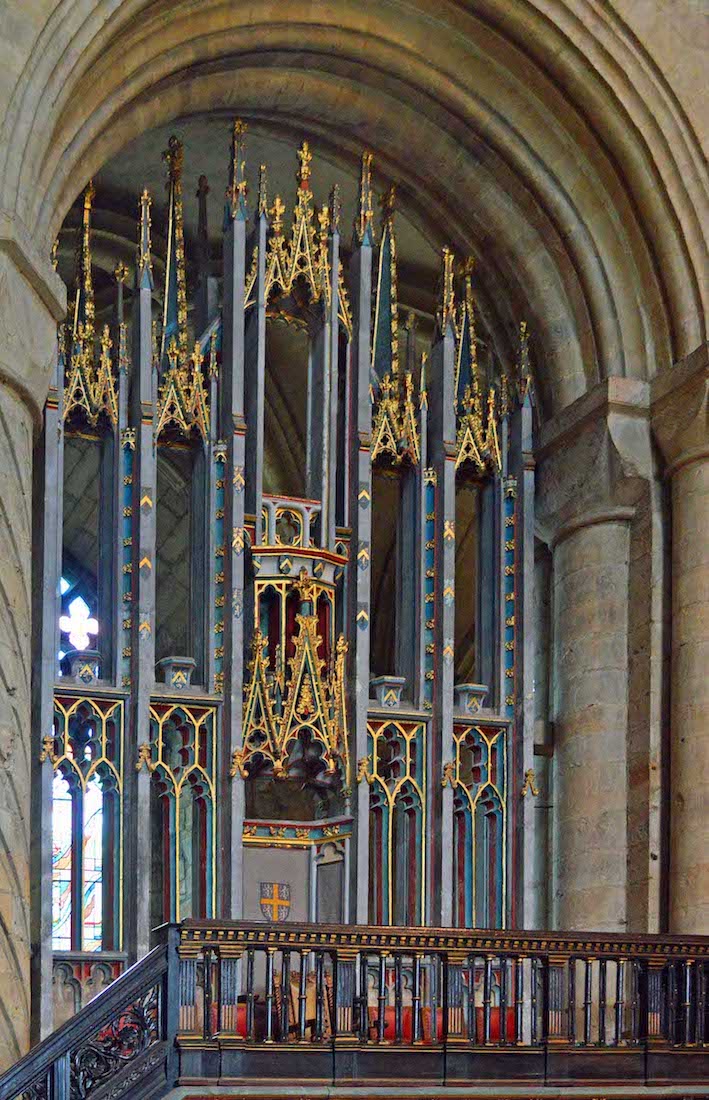

95. TO THE QUIRE

We leave the Venerable Bede and the Galilee Chapel, and return to the crossing, and then through the arch in the choir screen. The central choir aisle has some interesting circular paving – it dates from the nineteenth century, and is the work of Sir George Gilbert Scott, whose inspiration probably came from Byzantine churches.

96. WEST FROM THE QUIRE

From the central quire aisle we can look back through the arch and down the nave aisle. We notice the bell ropes hanging down at right. Again I am reminded of words like permanence, solidity, a faith ‘built on the rock’, ... . The quire is the heart of the Cathedral. Here worship has been offered to God every day for over 900 years.

97. QUIRE STALLS

The beautifully carved dark wooden choir stalls with elaborate ends and poppyheads date from the 1660s and were part of the Bishop Cosin renovations after the Restoration. When Cosin became bishop he inherited a Cathedral badly damaged by the Civil War, and bereft of much of its woodwork. Stalls at the back have misericords and are set under tall crocketted and pinnacled canopies with the names of the canon occupying each painted on the back.

98. QUIRE PAVING

As we move up towards the sanctuary, the central aisle widens and the paving becomes more elaborate – and impressively beautiful.

99. BISHOP HATFIELD CHANTRY

On the South side we arrive back at the Bishop Hatfield chantry: we viewed the back of this previously. Thomas Hatfield (c. 1310–81) rose to become a valued royal servant under King Edward III. Clerical careers in royal administration could lead to ecclesiastical office through royal patronage, and Hatfield’s qualities marked him for early promotion. In 1345 he was elected Bishop of Durham, an office he held until his death.

100. CATHEDRA

The 14th century Bishop’s Throne, ‘the highest in Christendom’, is ensconced above the memorial and tomb of Bishop Hatfield, founder of Durham and Trinity Colleges, Oxford. It is this throne – ‘cathedra’ in Latin – which marks this Durham Church as a cathedral.