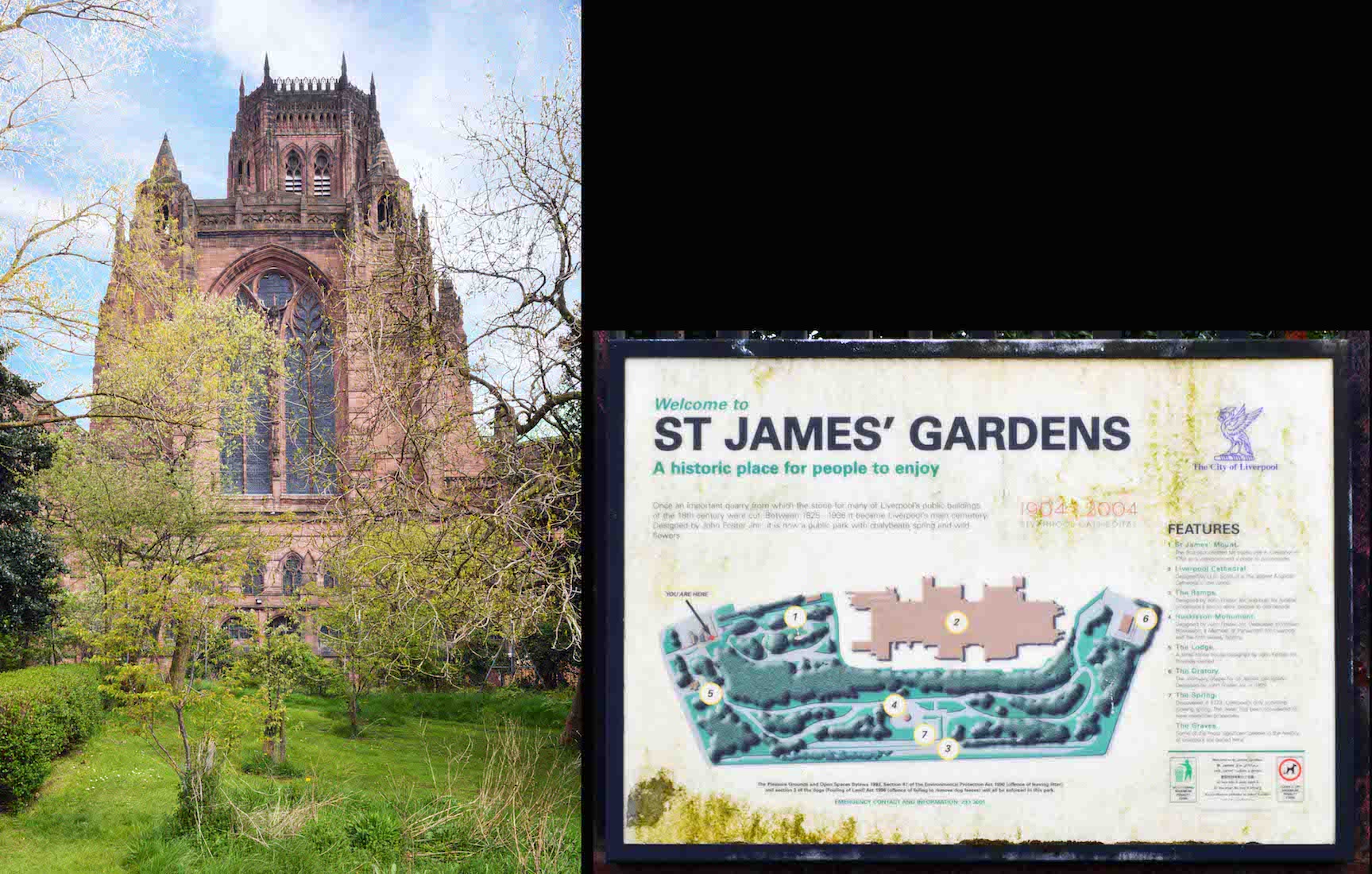

We approach the West end of the Cathedral from Lime Street Station, and immediately make the short descent to St James Park. This is an urban park below ground level that lies behind Liverpool Cathedral. Until 1825, the space was a stone quarry, and until 1936 it was used as the Liverpool city cemetery. It has been designated a Grade I Historic Park by Historic England. PLAN

2. TOWERING ABOVE

The Cathedral occupies most of a rock outcrop above the park known as St James Mount (also known as Quarry Hill or Mount Zion), which in 1771 was established as Liverpool's first public park. It may be referred to as the ‘Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool’ (as recorded in the Document of Consecration) or the ‘Cathedral Church of the Risen Christ’, Liverpool, being dedicated to Christ ‘in especial remembrance of his most glorious Resurrection’. Liverpool Cathedral is the largest cathedral and religious building in Britain.

3. PARK AND TOWER

We shall walk the length of St James’ Park, following around the North side of the Cathedral. The Cathedral is based on a design by Giles Gilbert Scott, and was constructed between 1904 and 1978. The total external length of the building, including the Lady Chapel (dedicated to the Blessed Virgin), is 207 yards (189 m) making it the longest cathedral in the world; its internal length is 160 yards (150 m).

4. NORTH TOWER AND WALL

Looking up from here we can see the tower and the West wall of the Cathedral. It is certainly large! In terms of overall volume, Liverpool Cathedral ranks as the fifth-largest cathedral in the world and contests with the incomplete Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City for the title of largest Anglican church building. With a height of 331 feet (101 m) it is also one of the world’s tallest non-spired church buildings and the third-tallest structure in the city of Liverpool.

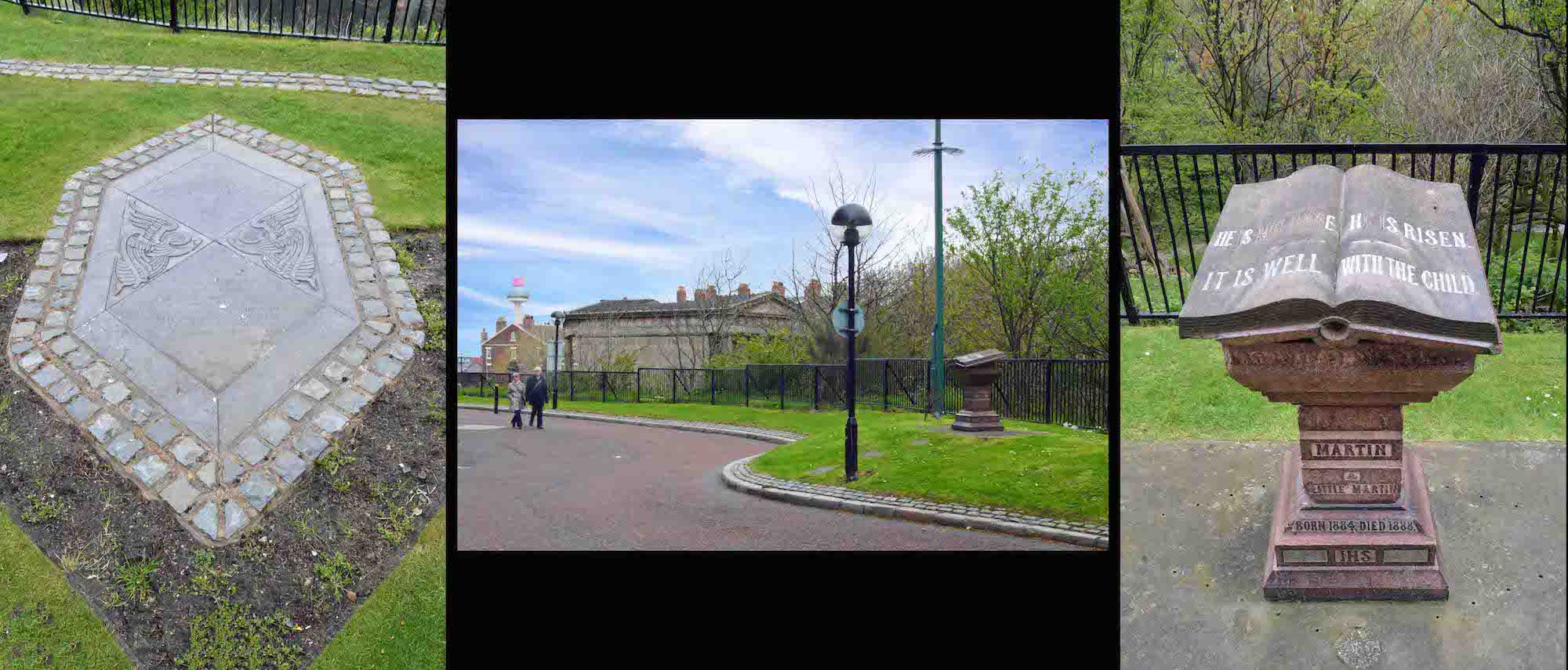

5. PARK REFLECTION

St James Park is a delightful place to take a stroll. In 1773 the quarry workers discovered a running spring, which still flows today, giving us pause for reflection! Ahead of us is the Huskisson Memorial, named for William Huskisson PC (1770 – 1830), a British statesman, financier, and Member of Parliament for several constituencies, including Liverpool. He is commonly known as the world’s first widely reported railway passenger casualty as he was run over and fatally wounded by George Stephenson’s pioneering locomotive engine, Rocket.

6. TOWARDS THE EAST

Continuing, we can view the Northeast transept and wall of the Cathedral. ••• John Charles Ryle was installed as the first Bishop of Liverpool in 1880, but the new diocese had no cathedral. In 1900 Francis Chavasse succeeded Ryle as Bishop, and immediately revived the project to build a cathedral. Chavasse, though himself an Evangelical, regarded the building of a great church as ‘a visible witness to God in the midst of a great city’.

7. EAST END

St James Park curves around to enclose the East end of the Cathedral. ••• In 1903, the assessors recommended a proposed plan submitted by the 22-year-old Giles Gilbert Scott, who was still an articled pupil, and had no existing buildings to his credit. He told the assessors that thus far his only major work had been to design a pipe-rack. The choice of winner was even more contentious with the Cathedral Committee when it was discovered that Scott was a Roman Catholic, but the decision stood. The foundation stone was laid by Edward VII in 1904.

8. A CLOSER VIEW

As we come near the end of St James Park, the East end of the Cathedral rises above us. ••• In 1909 Scott submitted an entirely new design for the main body of the cathedral. His original design had two towers at the West end and a single transept; the revised plan called for a single central tower 85 metres (280 ft) high, topped with a lantern and flanked by twin transepts. The new plans provided more interior space, and replaced much of the Gothic detailing with a more modern monumental style. The Cathedral Committee finally approved the new plans in Novemeber 1910.

9. SOUTHEAST VIEW, LADY CHAPEL

In our circuit of the Cathedral we come up from St James Park to the car park! The Lady Chapel lies immediately before us, and just beyond, an ornamental arch protrudes. ••• The Lady Chapel (originally intended to be called the Morning Chapel), was the first part of the building to be completed. It was consecrated in 1910 by Chavasse in the presence of two Archbishops and 24 other Bishops. The richness of the décor of the Lady Chapel may have dismayed some of Liverpool’s Evangelical clergy, who would have seen it as being designed for Anglo-Catholic worship.

10. SOUTHERN ARCH

The purpose of this arch, apart from delineating the end of the Lady Chapel, is unclear. The Lady Chapel sign indicates that it can be used as an entryway to the Chapel. It is decorated with a number of cherubic and child-like figures, with Christ seated top centre. ••• Work was severely limited during WWI, with a shortage of manpower, materials and donations. By 1920, the workforce had been brought back up to strength and the stone quarries at Woolton, source of the pinkish-red sandstone for most of the building, reopened.

11. CLOSER VIEW

••• The first section of the main body of the cathedral was complete by 1924. It comprised the chancel, an ambulatory, chapter house and vestries. The section was closed off with a temporary wall, and on 19 July 1924, the 20th anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone, the cathedral was consecrated in the presence of George V and Queen Mary, and Bishops and Archbishops from around the globe.

12. AROUND THE EAST END

We retrace our steps and walk around the Lady Chapel to the chapter house at the Northeast corner. ••• After the consecration of the Cathedral, major works ceased for a year while Scott once again revised his plans for the next section of the building: the tower, the under-tower and the central transept. The tower in his final design was higher and narrower than his 1910 conception.

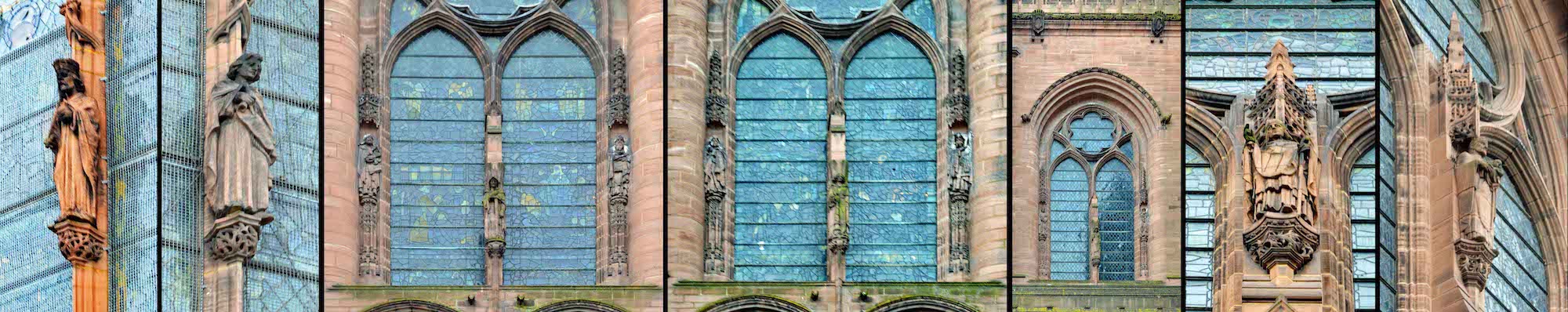

13. NORTH WINDOW FIGURES

The North wall of the Cathedral looks out over St James Park. Along this wall, various religious figures adorn the stone window framework. ••• From July 1925 work continued steadily, and it was hoped to complete the whole section by 1940. The outbreak of WWII in 1939 caused similar problems to those of the earlier war. The workforce dwindled from 266 to 35; moreover, the building was damaged by German bombs. Despite these vicissitudes, the central section was complete enough by July 1941 to be handed over to the Dean and Chapter. Scott laid the last stone of the last pinnacle on the tower on 20 February 1942. No further major works were undertaken during the rest of the war. Scott produced his plans for the nave in 1942, but work on it did not begin until 1948. The bomb damage, particularly to the Lady Chapel, was not fully repaired until 1955.

14. WEST END MEMORIALS

We return to the West end of the Cathedral, near where we began. At left is a memorial stone to Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880–1960), ‘loved father and architect of this Cathedral’, and to his wife. The memorial at right reads: ‘He is not here, he is risen. It is well with the child. Born 1881 – Died 1887. Martin & Little Martin Born 1884 – Died 1888 IHS’. I can find no identifying reference to either Martin.

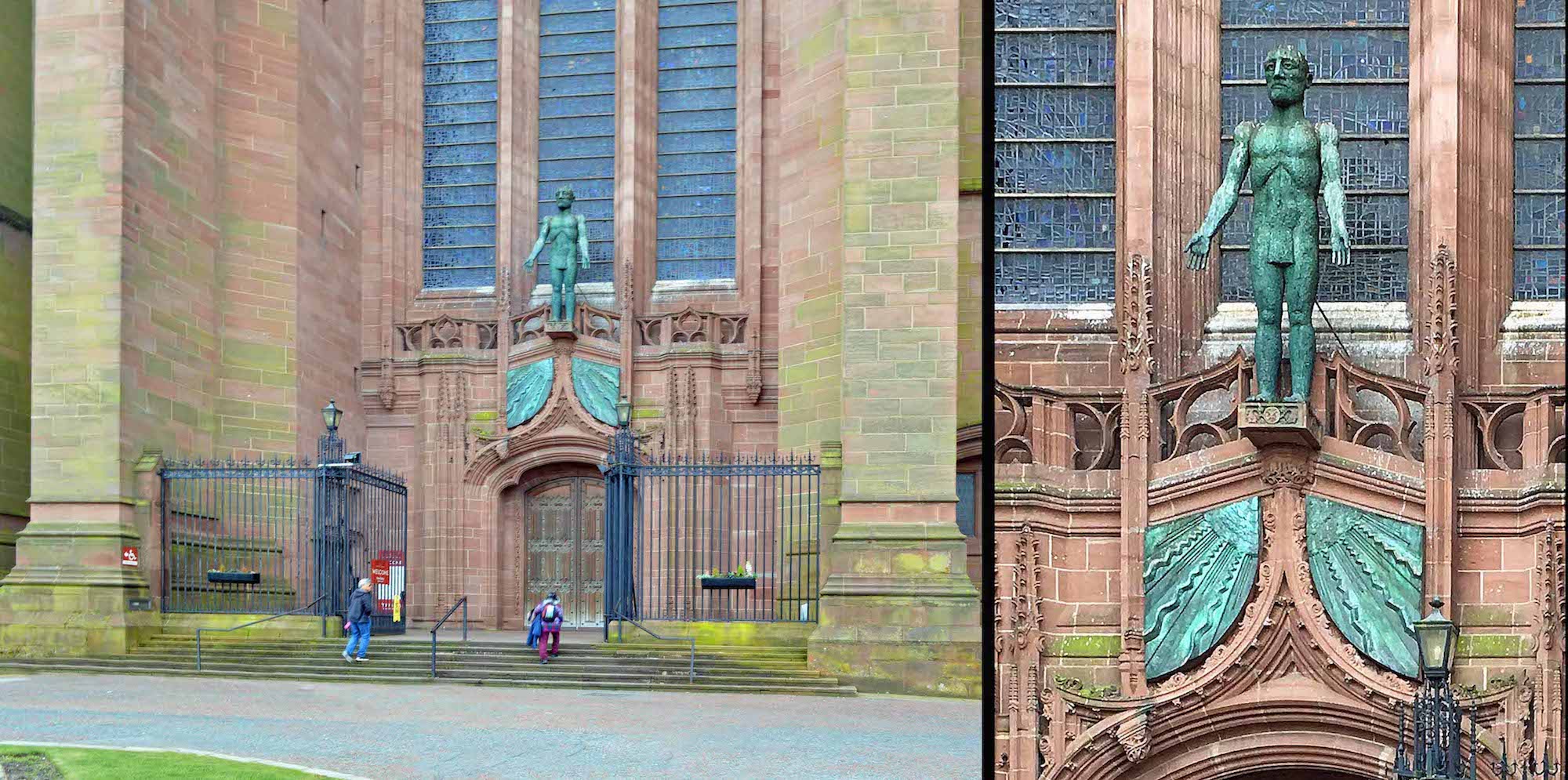

15. WEST DOORWAY

At the West end of the Cathedral we are able to enter next to the West doors. Above the entry is ‘The Welcoming Christ’, a work by Elisabeth Frink. We shall return here shortly to go inside, but there is a little more to see first on the exterior. ••• Giles Gilbert Scott died in 1960. The first bay of the nave was then nearly complete, and was handed over to the Dean and Chapter in April 1961.

16. SOUTH WALL FROM THE SOUTHWEST

To complete our external investigation we need to follow along the South wall to the Lady Chapel. ••• Scott was succeeded as architect by Frederick Thomas. Thomas, who had worked with Scott for many years, drew up a new design for the West front of the cathedral. The Guardian commented, ‘It was an inflation beater, but totally in keeping with the spirit of the earlier work, and its crowning glory is the Benedicite Window designed by Carl Edwards and covering 1,600 sq. ft.’

17. ENTRY TO THE GILES GILBERT SCOTT SUITE

Partway along the south wall is this entrance to the Giles Gilbert Scott Suite. This is a function centre with two oak-panelled rooms, each holding up to 100 guests. ••• The completion of the building was marked by a service of thanksgiving and dedication in October 1978, attended by Queen Elizabeth II. In the spirit of ecumenism that had been fostered in Liverpool, Derek Worlock, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Liverpool, played a major part in the ceremony.

18. RANKIN PORCH

The Rankin Porch, and the matching Welsford Porch on the North side, open out off the large central space of the Cathedral. The doors of the Rankin Porch are generally closed, but the doors of the Welsford Porch can give access to a vaulted vestibule now used as a café.

19. SANCTUARY SOUTH WALL

The Rankin Porchand on this side, the Welsford porch, lie between the two transepts. Here we are Eest of the South (Derby) transept, with the windows of the South chancel above us. To our right is the Southern arch and Lady Chapel we have seen before. This completes our circumnavigation of the Cathedral, but there is one more interesting feature to note.

20. WWII DAMAGE

Closer inspection of a section of this South wall just West of the Rankin Porch reveals a number of indentations in the stone. These were the result of a strafing run by the German airforce during WWII. There was more significant bomb damage to the Lady Chapel in particular; this was not fully repaired until 1955. We now return to the West door and enter the Cathedral.