PETERBOROUGH CATHEDRAL

CAMBRIDGESHIRE ENGLAND

PAUL SCOTT

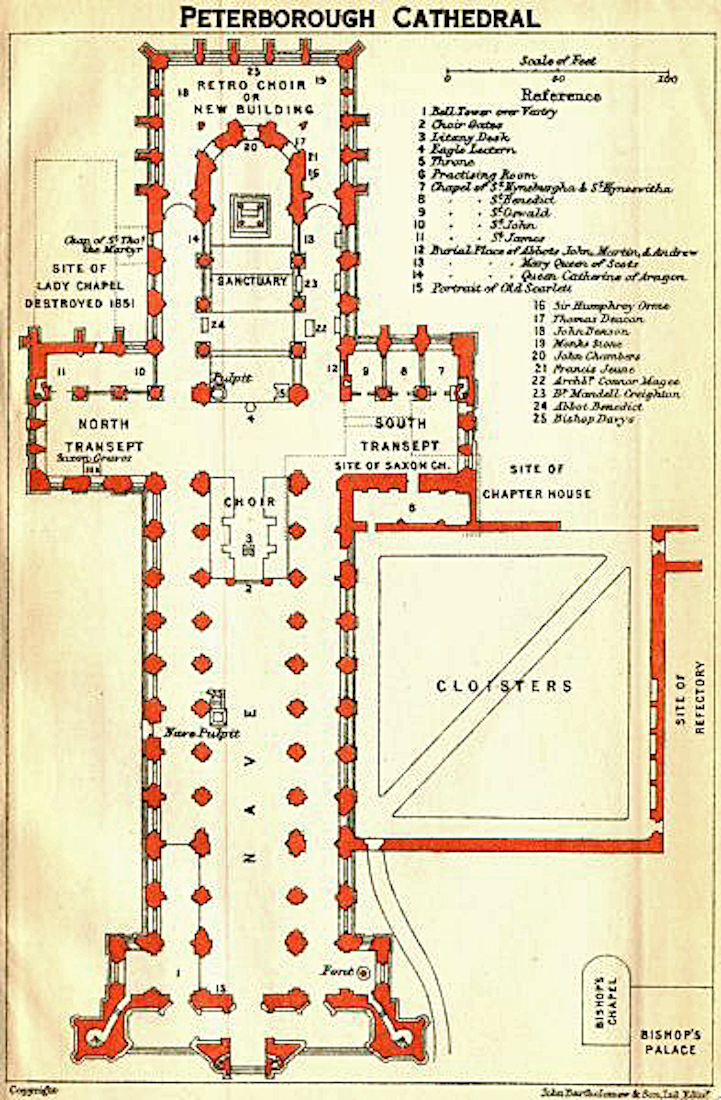

Peterborough Cathedral is cruciform in shape with a large cloister area abutting the nave on the South side. The plan as shown is rotated anticlockwise through exactly 90° from the Cathedral’s actual position, as indicated by the North and South transepts.

The nave is very long, and includes the choir area on the nave side of the crossing. Chapels are found at bottom right, and also along the East wall of the South transept. The Cathedral treasury lies along the East wall of the North transept. The sanctuary forms a higher part of the Cathedral, surrounded by the side aisles and the New Building at the East (upper) end.

A brief history of the Cathedral is given below. However if you want to begin your tour of the Cathedral immediately, tap /click on START .

Intermediate points of the tour can be accessed by clicking / tapping on the links below.

NOTE ON MAGNIFYING IMAGES

With this website format the images are large enough for most purposes. If there is a need for greater magnification of an image, go to the identical photo on

https://www.flickr.com/photos/paulscottinfo/albums

and use Command - + (Mac) or Windows - + (Windows).

HISTORY

[Wikipedia]

Anglo-Saxon origins

The original church, known as ‘Medeshamstede’, was founded in the reign of the Anglo-Saxon King Peada of the Middle Angles in about 655 AD, as one of the first centres of Christianity in central England. The monastic settlement with which the church was associated lasted at least until 870, when it was supposedly destroyed by Vikings. In an alcove of the New Building, an extension of the Eastern end, lies an ancient stone carving: the Hedda Stone. This medieval carving of twelve monks, six on each side, commemorates the destruction of the Monastery and the death of the Abbot and Monks when the area was sacked by the Vikings in 864. The Hedda Stone was likely carved sometime after the raid, when the monastery slipped into decline.

In the mid-10th century monastic revival (in which churches at Ely and Ramsey were also refounded) a Benedictine Abbey was created and endowed in 966, principally by Athelwold, Bishop of Winchester, from what remained of the earlier church, with ‘a basilica [church] there furbished with suitable structures of halls, and enriched with surrounding lands’ and more extensive buildings which saw the aisle built out to the west with a second tower added. The original central tower was, however, retained. It was dedicated to St Peter and surrounded by a palisade, called a burgh, hence the town surrounding the abbey was eventually named Peter-burgh. The community was further revived in 972 by Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury.

This newer church had as its major focal point a substantial Western tower with a ‘Rhenish helm’ and was largely constructed of ashlars. Only a small section of the foundations of the Anglo-Saxon church remain beneath the South transept but there are several significant artefacts, including Anglo-Saxon carvings such as the Hedda Stone, from the earlier building.

In 2008, Anglo-Saxon grave markers were reported to have been found by workmen repairing a wall in the cathedral precincts. The grave markers are said to date to the 11th century, and probably belonged to ‘townsfolk’.

Norman and medieval architectural evolution

Although damaged during the struggle between the Norman invaders and local folk-hero, Hereward the Wake, it was repaired and continued to thrive until destroyed by an accidental fire in 1116. This event necessitated the building of a new church in the Norman style, begun by Abbot John de Sais on 8 March 1118. By 1193, the building was completed to the Western end of the nave, including the central tower and the decorated wooden ceiling of the nave. The ceiling, completed between 1230 and 1250, still survives. It is unique in Britain and one of only four such ceilings in the whole of Europe. It has been over-painted twice, once in 1745, then in 1834, but still retains the character and style of the original. (The painted nave ceiling of Ely Cathedral, by contrast, is entirely a Victorian creation.)

The church was largely built of Barnack limestone from quarries on its own land, and it was paid annually for access to these quarries by the builders of Ely Cathedral and Ramsey Abbey in thousands of eels (e.g. 4,000 each year by Ramsey). Cathedral historians believe that part of the placing of the church in the location it is in is due to the easy ability to transfer quarried stones by river and then to the existing site allowing it to grow without being relocated.

Then, after completing the Western transept and adding the Great West Front Portico in 1237, the medieval masons switched over to the new Gothic style. Apart from changes to the windows, the insertion of a porch to support the free-standing pillars of the portico and the addition of a ‘new’ building at the East end around the beginning of the 16th century, the structure of the building remains essentially as it was on completion almost 800 years ago. The completed building was consecrated in 1238 by Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, within whose diocese it then fell.

The trio of arches forming the Great West Front, the defining image of Peterborough Cathedral, is unrivalled in medieval architecture. The line of spires behind it, topping an unprecedented four towers, evolved for more practical reasons. Chief amongst them was the wish to retain the earlier Norman towers, which became obsolete when the Gothic front was added. Instead of being demolished and replaced with new stretches of wall, these old towers were retained and embellished with cornices and other gothic decor, while two new towers were added to create a continuous frontage.

The Norman tower was rebuilt in the Decorated Gothic style in about 1350–1380 (its main beams and roof bosses survive) with two tiers of Romanesque windows combined into a single set of Gothic windows, with the turreted cap and pinnacles removed and replaced by battlements. Between 1496 and 1508, the Presbytery roof was replaced and the ‘New Building’, a rectangular building built around the end of the Norman eastern apse, with Perpendicular fan vaulting (probably designed by John Wastell, the architect of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge and the Bell Harry Tower at Canterbury Cathedral), was added.

Monastic life

The existing mid-12th-century records of Hugh Candidus, a monk, list the Abbey’s reliquaries as including two pieces of swaddling clothes which wrapped the baby Jesus, pieces of Jesus’ manger, a part of the five loaves which fed the 5,000, a piece of the raiment of Mary the mother of Jesus, a piece of Aaron’s rod, and relics of St Peter, St Paul and St Andrew – to whom the church is dedicated.

The supposed arm of Oswald of Northumbria disappeared from its chapel, probably during the Reformation, despite a watch-tower having been built for monks to guard its reliquary. Various contact relics of Thomas Becket were brought from Canterbury in a special reliquary by its Prior Benedict (who had witnessed Becket’s assassination), when he was ‘promoted’ to Abbot of Peterborough.

These items underpinned the importance of what is today Peterborough Cathedral. At the zenith of its wealth just before the Reformation it had the sixth-largest monastic income in England, and had 120 monks, an almoner, an infirmarian, a sacristan and a cellarer.

Tudor

In 1541, following Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, the relics were lost. The church survived by being selected as the Cathedral of the Anglican Diocese of Peterborough. Henry’s former wife, Catherine of Aragon, had been buried there in 1536. Her grave can still be seen and is still honoured by visitors who decorate it with flowers and pomegranates (her symbol). It carries the legend ‘Katharine Queen of England’, a title she was denied at the time of her death.

In 1587, the body of Mary, Queen of Scots was initially buried here after her execution at nearby Fotheringhay Castle, but it was later removed to Westminster Abbey on the orders of her son, King James I of England.

Civil War to present

The Cathedral was vandalised during the English Civil War in 1643 by Parliamentarian troops. As was common at the time, almost all the stained glass and the medieval choir stalls were destroyed, and the high altar and reredos were demolished, as were the cloisters and Lady Chapel. All the monuments and memorials of the Cathedral were also damaged or destroyed.

Some of the damage was repaired during the 17th and 18th centuries. Extensive restoration work began in 1883, which was initiated after large cracks appeared in the supporting pillars and arches of the main tower. These works included rebuilding of the central tower and its foundations, interior pillars, the choir and re-enforcements of the West front under the supervision of John Loughborough Pearson. New hand-carved choir stalls, cathedra (bishop’s throne), choir pulpit and the marble pavement and high altar were added. A stepped level of battlements was removed from the central tower, reducing its height slightly.

The Cathedral was hit by a fire on the early evening of 22 November 2001; it is thought to have been started deliberately amongst plastic chairs stored in the North Choir Aisle. Fortunately the fire was spotted by one of the vergers allowing a swift response by emergency services. The timing was particularly unfortunate, for a complete restoration of the painted wooden ceiling was nearing completion. The oily smoke given off by the plastic chairs was particularly damaging, coating much of the building with a sticky black layer. The seat of the fire was close to the organ and the combination of direct damage from the fire, and the water used to extinguish necessitated a full-scale rebuild of the instrument, putting it out of action for several years.

An extensive programme of repairs to the West front began in July 2006 and has cost in excess of half a million pounds. This work is concentrated around the statues located in niches which have been so badly affected by years of pollution and weathering that, in some cases, they have only stayed intact thanks to iron bars inserted through them from the head to the body. The programme of work has sought donors to ‘adopt a stone’.

The sculptor Alan Durst was responsible for some of the work on the statues on the West Front.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peterborough_Cathedral