EXTERIOR

Emerging from St Paul’s Underground Station onto Cheapside, I see no sign of the famous cathedral – just rows of apartment buildings. I ask a man sitting waiting for a bus. He laughs and points back over his shoulder. “I’m often asked that,” he says. As directed, I look down Queen’s Head Passage ... and there it is!

XT2. SHEPHERD IN PATERNOSTER SQUARE

Half way along the Passage, a short turn-off to the right brings me to Paternoster Square and this wonderful sculpture of shepherd and sheep. The sculpture is called ‘Paternoster’, also known as ‘Shepherd and Sheep’ or ‘Shepherd with his Flock’, and is an outdoor 1975 bronze sculpture by Elisabeth Frink. It depicts a shepherd herding five sheep. The subject of the statue reflects the former use of Paternoster Row as the site of Newgate Market for the sale of livestock and meat, and may also have theological overtones reflecting its position in the shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral.

XT3. ST PAUL’S FROM THE SQUARE

From the Square there are two main views of the nearby Cathedral: the famous dome, and the twin towers of the Western wall. The name of the Square comes from the medieval street which was on this site: Paternoster Row. After the Great Fire of London wiped out the multitude of shops here, it became the heart of London’s publishing trade before Fleet Street took the title.

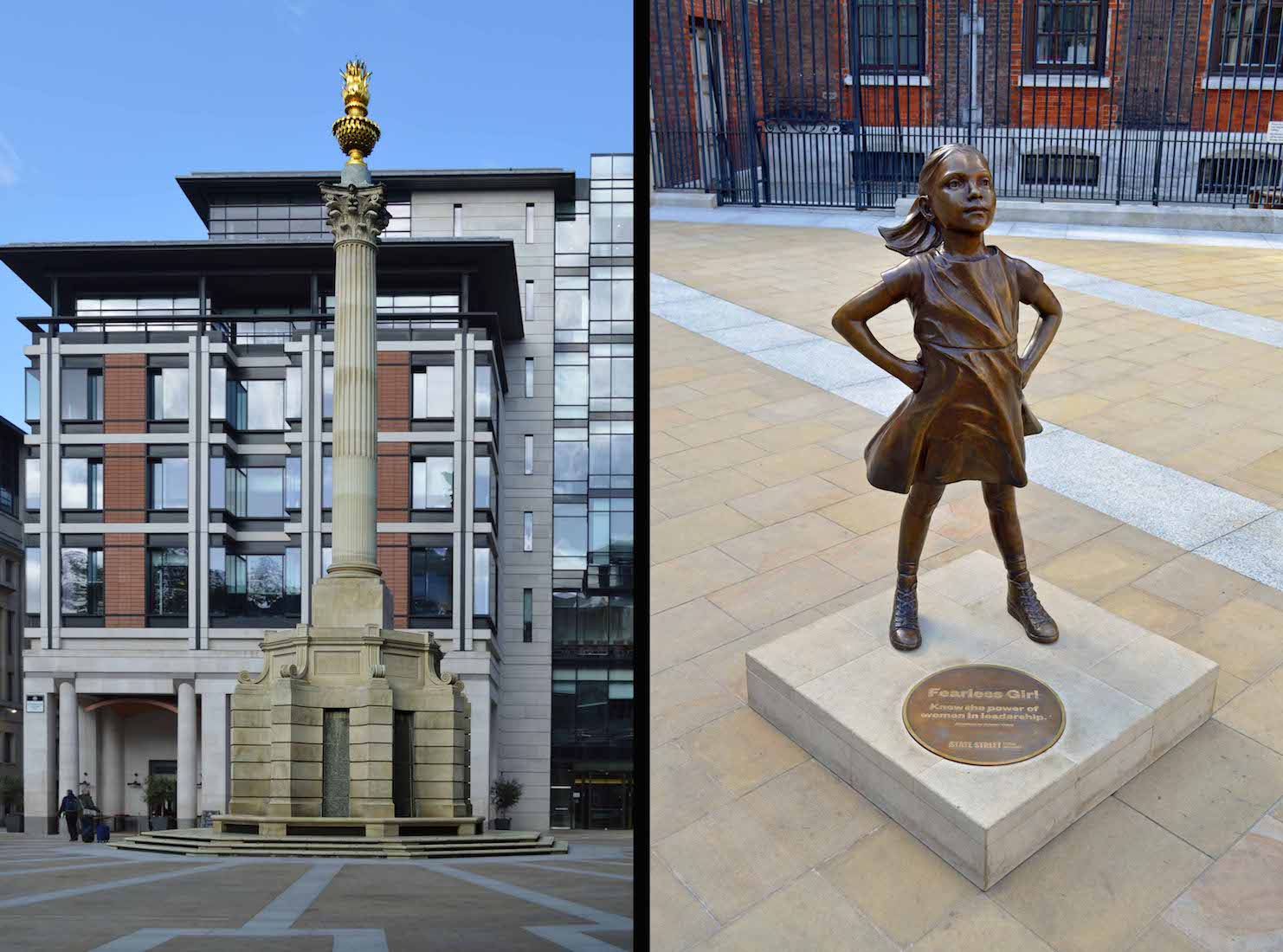

XT4. COLUMN AND FEARLESS GIRL

Before we leave the Square there are two other items to notice. One is a huge column, 23.3m high, and based on Inigo Jones’ Corinthian columns for St Paul’s West Portico, destroyed in favour of the Wren design we see today. There is an urn with flames at the top: this is because the column commemorates both the fires that destroyed this area, in 1666 and 1940. The statue is ‘Fearless Girl’ by Kristen Visbal, a bronze statue of a defiant girl, installed in London’s financial district in March 2019 to highlight the importance of female leaders in business. It is a copy of a statue that became famous for ‘staring down’ Wall Street’s bull after it was unveiled in New York City in 2017. This installation was to be temporary, so the defiant young lady is probably no longer here.

XT5. LOOKING UP TO THE DOME

We return to the Queen’s Head Passage and look up to the impressive dome of St Paul’s Cathedral. This dome, which has long dominated the London skyline, is composed of three shells: an outer dome, a concealed brick cone for structural support, and an inner dome. The cross atop its outer dome stands nearly 366 feet (112 metres) above ground level.

XT6. SOUTHEAST VIEW

We turn left and follow a path amongst the many trees growing just around here. Wherever we go, the dome is the focus of our attention. We quickly come to St Paul’s Cross.

XT7. ST PAUL’S CROSS

St Paul’s Cross was a preaching cross and open-air pulpit in the grounds of Old St Paul’s Cathedral. It was the most important public pulpit in Tudor and early Stuart England, and many of the most important statements on the political and religious changes brought by the Reformation were made public from here. A monument stands in this area of the Cathedral precinct now, but it is not on the exact spot where St Paul’s Cross stood.

XT8. CROSS PLAQUE

At the base of the monument is a copper plaque with the words: ‘On this plot of ground stood of old “Paul’s Cross” whereat amid such scenes of good and evil as make up human affairs, the conscience of church and nation through five centuries found public utterance. The first record of it is in 1191 AD. It was rebuilt by Bishop Kemp in 1449, and was finally removed by the order of the Long Parliament in 1643. This cross was re-erected in its present form under the will of H.C. Richards to recall and renew the ancient memories.’ The pulpit stood from 1449 until 1635, when it was taken down during Inigo Jones’ renovation work.

XT9. SOUTHEAST CORNER AND DECORATION

We continue our exploration around the East end of the Cathedral. The Cathedral is built of Portland Stone. There is some attractive decoration beneath the windows here.

XT10. EASTERN FACE

The Eastern end of the Cathedral houses the quire, sanctuary and high altar. The curved end is an apse, but it is interesting that the upper wall on either side is just that: a wall enclosing an unroofed section, with the much lower (roofed!) quire aisle below.

XT11. CHURCHYARD

The grounds at the East end of the Cathedral are very attractive – grassed with many shrubs and trees. This is the view of the South Churchyard which extends from here to the South transept. We can just see an unusual sculpture in the distance.

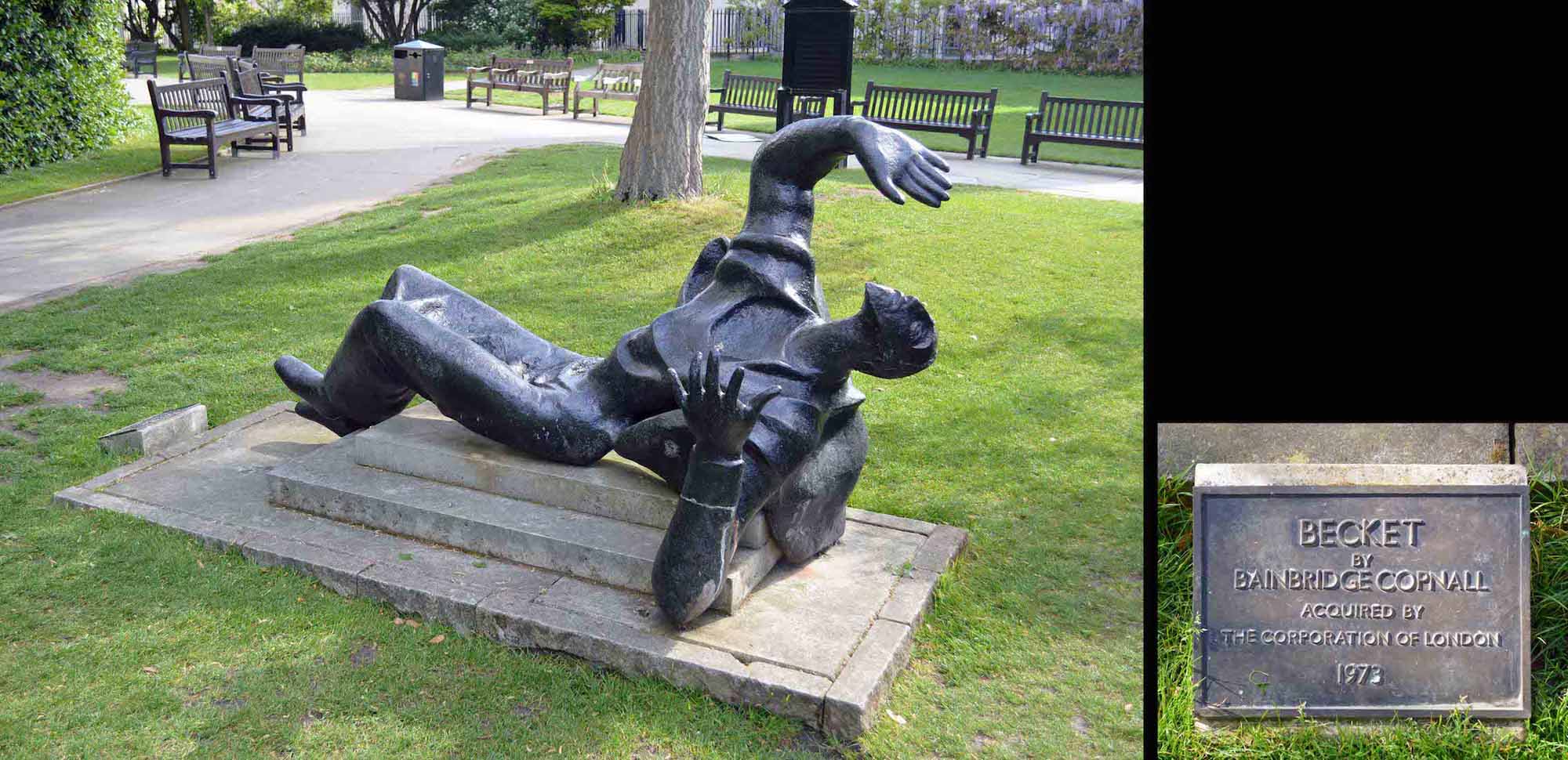

XT12. BECKET SCULPTURE

The Becket (or St Thomas à Becket) sculpture is a fibreglass resin creation made in 1970-71 by E. Bainbridge Copnall, and installed in St Paul’s Cathedral Churchyard in 1973. The figurative sculpture depicts the prostrate figure of St Thomas à Becket at the moment of his martyrdom in the choir of Canterbury Cathedral. The head is thrown back and the hands are extended as if to ward off the blows of his assassins, and the face is vigorously rendered with an elongated chin, pointed nose and lentoid eyes with heavy eyelids. After sustaining damage in the storm of 1987, the sculpture was restored by Copnall’s former student Patrick Crouch and re-mounted on a low plinth. The sculpture was again restored in 2001 after being vandalised and again restored in 2013. In his restoration, Patrick Crouch added a hood to the flowing drapery of the gown, to increase the stability of the sculpture.

XT13. TRANSEPT AND SOUTH WALL

This section of the Churchyard feels quite enclosed with high Cathedral walls on two sides. However it is a pleasant little oasis in busy London.

XT14. VIEW FROM FESTIVAL GARDENS

Leaving Churchyard we move to nearby Festival Gardens for a more distant view of the Cathedral. Always that dome! Redesigned as part of the City’s contribution to the Festival of Britain in 1951, these gardens were originally laid out over a large expanse of bomb-damaged land after the Second World War. The site was formerly that of Old Change, a street dating from 1293. The formal layout consists of a sunken lawn with wall fountain, which was a gift of the Worshipful Company of Gardeners. The west of the garden features the sculpture ‘The Young Lovers’ by Georg Ehrlich which was erected in 1973. The lawn is surrounded by a raised paved terrace with stone parapets and seating, planting in tubs and a number of trees. The garden offers an excellent view of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

XT15. WALKING UP ST PAUL’S CHURCHYARD

Confusingly, ‘St Paul’s Churchyard’ is also the name of the road that passes by this side of the Cathedral. We leave the Festival Gardens, and follow up this road. A large structure is on the footpath ahead of us.

XT16. FOUNTAIN AND SOUTH TRANSEPT

Nearly opposite the Gardens is this St Lawrence and Mary Magdalene Drinking Fountain. The fountain was originally installed in 1866 outside the Church of St Lawrence Jewry next Guildhall, and moved here in 2010. The fountain is impressively large, but not when viewed against St Paul’s.

XT17. CATHEDRAL TOWERS

Our approach to the West façade is signalled by the appearance of the impressive twin Western towers with their sculpted detailing and gold accents.

XT18. WAR SCULPTURE AND VIEW

A little further on we come to the National Firefighters’ Memorial on Peter’s Hill / Sermon Lane. The memorial is composed of three bronze statues depicting firefighters in action at the height of the Blitz. If we followed down Peter’s Hill we would come to the Millenium Bridge – a pedestrian bridge across the Thames from where it is possible to get distant views of St Paul’s dome.

XT19. CATHEDRAL CLOCK

The clock contained in the Southwest tower has a mechanism built in 1893 by Smith of Derby. The design is similar to that used by Edward Dent on the ‘Big Ben’ mechanism in 1895. The clock mechanism is 5.8 metres long and is the most recent of the clocks introduced to St Paul’s Cathedral over the centuries. Since 1969 the clock has been electrically wound with equipment designed and installed by Smith of Derby, relieving the clock custodian of the work of cranking up the heavy drive weights.

XT20. WEST WALL

St. Paul’s is without doubt the grandest building in London. Perhaps the finest view is obtained from the approach by Ludgate Hill. The style is English Renaissance. The West Front was the last part of the Cathedral erected, and therefore bears the stamp of Wren’s matured genius.