Wells Cathedral, the Cathedral Church of Saint Andrew, is an Anglican cathedral in Wells, Somerset. The Cathedral is the seat of the Bishop of Bath and Wells. It was built between 1175 and 1490, replacing an earlier Saxon church built on the same site in 705. With its broad West front and large central tower, it is the dominant feature of its small cathedral city and a landmark in the Somerset countryside. Wells has been described as ‘unquestionably one of the most beautiful’ and as ‘the most poetic’ of English cathedrals. PLAN

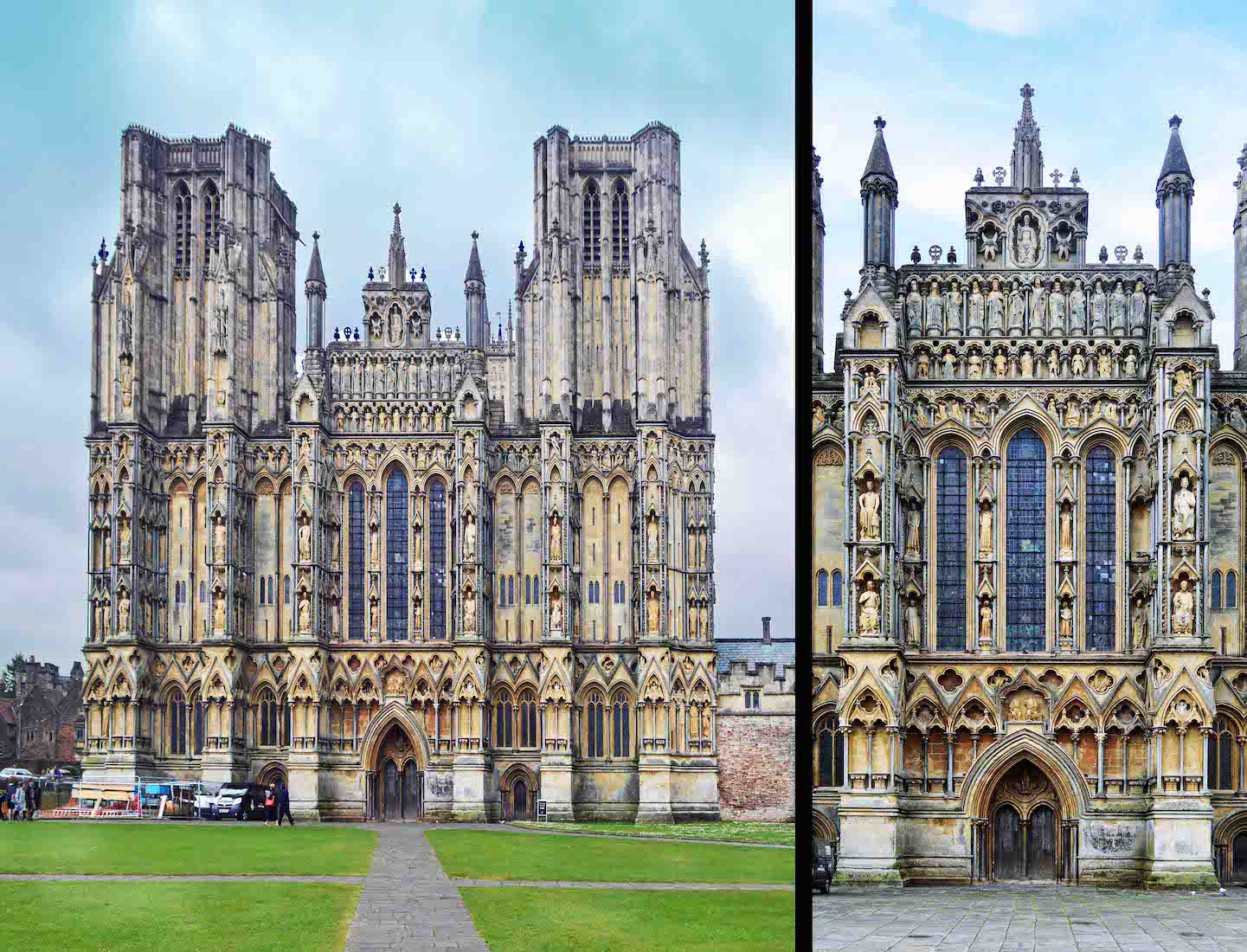

2. WEST WALL

The Early English West front was commenced around 1230 by Thomas Norreys, with building and sculpture continuing for thirty years. Its Southwest tower was begun 100 years later and constructed between 1365 and 1395, and the Northwest tower between 1425 and 1435, both in the Perpendicular Gothic style to the design of William Wynford, who also filled many of the Cathedral’s early English lancet windows with delicate tracery.

3. WEST WALL DETAIL

The West front has three distinct horizontal layers, and six strongly projecting vertical buttresses defining the cross-sectional divisions of nave, aisles and towers. Above the basement the two storeys are ornamented with quatrefoils and niches originally holding about four hundred statues, with three hundred surviving until the mid-20th century. Since then, some have been restored or replaced, including the figure of the risen Christ in the gable. Below are the figures of the twelve disciples.

4. NORTHWEST DETAIL AND WEST DOOR

The West doorway is surprisingly modest for a grand cathedral. A figure of the Madonna and Child sits in the gable above. I always try to circumnavigate around the outside of a cathedral, so we move in a clockwise direction to the base of the Northwest tower. There is detailed carving here and many statues, unfortunately damaged by the weather. The use of the corner niches is interesting.

5. VIEW EAST ALONG THE NORTH WALL

In this view, the central tower is seen at right, and the North transept. Closer at right is an entry to the nave. Ahead we can see the top of the chapter house, accessed by a staircase which also leads to the link across the roadway to the Vicars’ Close. • The Cathedral’s architecture presents a harmonious whole which is entirely Gothic and mostly in the Early English style of the late 12th and early 13th centuries. In this respect Wells differs from most other English medieval cathedrals, which have parts in the earlier Romanesque style introduced to Britain by the Normans in the 11th century.

6. TRANSEPT CLOCK AND NORTH DOOR

There is no entry to the nave through this multi-arched doorway. The arch has a small emblem on either side, and the stones lining the pathway are of interest. Later we shall discover a very interesting astronomical clock within the North transept. This dial mounted on the outside wall is driven from the same mechanism. The clock was first installed in the 14th or 15th centuries, but has been restored a number of times.

7. CHAPTER HOUSE AND LINK

The chapter house is the only octagonal chapter house to be built as a first storey on top of an undercroft, which was the ‘strong room’ of the Cathedral. A crypt would not have been practical because of underground water. The undercroft itself, with its rugged supporting pillars, was certainly constructed by 1266, just after the completion of the West Front, but work, first on the staircase (1265-1280) and then on the chapter house itself (1286-1306), proceeded slowly. The link walkway is accessed from the top of the staircase.

8. VICARS’ CLOSE

Vicars’ Close is claimed to be the oldest purely residential street with original buildings surviving intact in Europe. John Julius Norwich calls it ‘that rarest of survivals, a planned street of the mid-14th century’. It comprises numerous Grade I listed buildings, comprising 27 residences (originally 44), built for Bishop Ralph of Shrewsbury, a chapel and library at the North end, and a hall at the South end, over an arched gate. It is connected at its Southern end to the cathedral by way of a walkway over Chain Gate.

9. CHAPTER HOUSE

Walking through Chain Gate we get a good view of the chapter house. • The Cathedral is thought to have been conceived and commenced in about 1175 by Bishop Reginald Fitz Jocelin, who died in 1191. From its size it is clear that from the outset, the original Church was planned to be the Cathedral of the diocese. However, the seat of the bishop moved between Wells and the abbeys of Glastonbury and Bath, before settling at Wells.

10. EAST END

Our circum-navigation of the Cathedral is starting to look doubtful! In this view, the chapter house is on our right. Ahead is the retroquire, leading to the Corpus Christi Chapel facing us, and the Lady Chapel behind the tree. • Adam Locke was master mason from about 1192 until 1230. The Church was designed in the new style with pointed arches, later known as Gothic. Work was halted between 1209 and 1213 when King John was excommunicated and Bishop Jocelin was in exile, but the main parts of the Church were complete by the time of the dedication by Bishop Jocelin in 1239.

11. END OF THE ROAD

Our exploration now leads us to this parking lot at the East end of the Cathedral, but with a couple of views of the East end. Of course, on reflection, our path around the Cathedral is going to be blocked by the Palace Gardens: we shall have to attempt a new strategy ... .

12. WEST CLOISTER

We retrace our steps to find the main Cathedral entrance near the High Street. This brings us through to the West Cloister. If we follow North as shown here we shall come to the Cathedral, but for now, we exit by the doorway on the right into the cloister garden. • In 1661, after Charles II was restored to the throne, Robert Creighton, the king's chaplain in exile, was appointed dean and was bishop for two years before his death in 1672. Following Creighton's appointment as bishop, the post of dean went to Ralph Bathurst, who had been chaplain to the king, president of Trinity College, Oxford, and FRS.

13. CLOISTER GARDEN I

The cloister ‘garden’ is mostly lawn with the occasional tree, and some graves. However, from here we do get a view of the Southwest tower and the South nave. • During Bathurst’s long tenure the cathedral was restored, but in the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685, Puritan soldiers damaged the West front, tore lead from the roof to make bullets, broke the windows, smashed the organ and furnishings, and for a time stabled their horses in the nave.

14. CLOISTER GARDEN II

The early cloisters were in place before the chapter house was complete but very little, apart from the lowest section of the outer walls remains, particularly in the East and West cloisters. All three cloisters were substantially remodelled in the 15th century. Bishop Bubwith (1407-24) left money in his will to build an impressive library above the east cloister, which was widened and strengthened to take the extra storey. This medieval library is thought to be the longest in England.

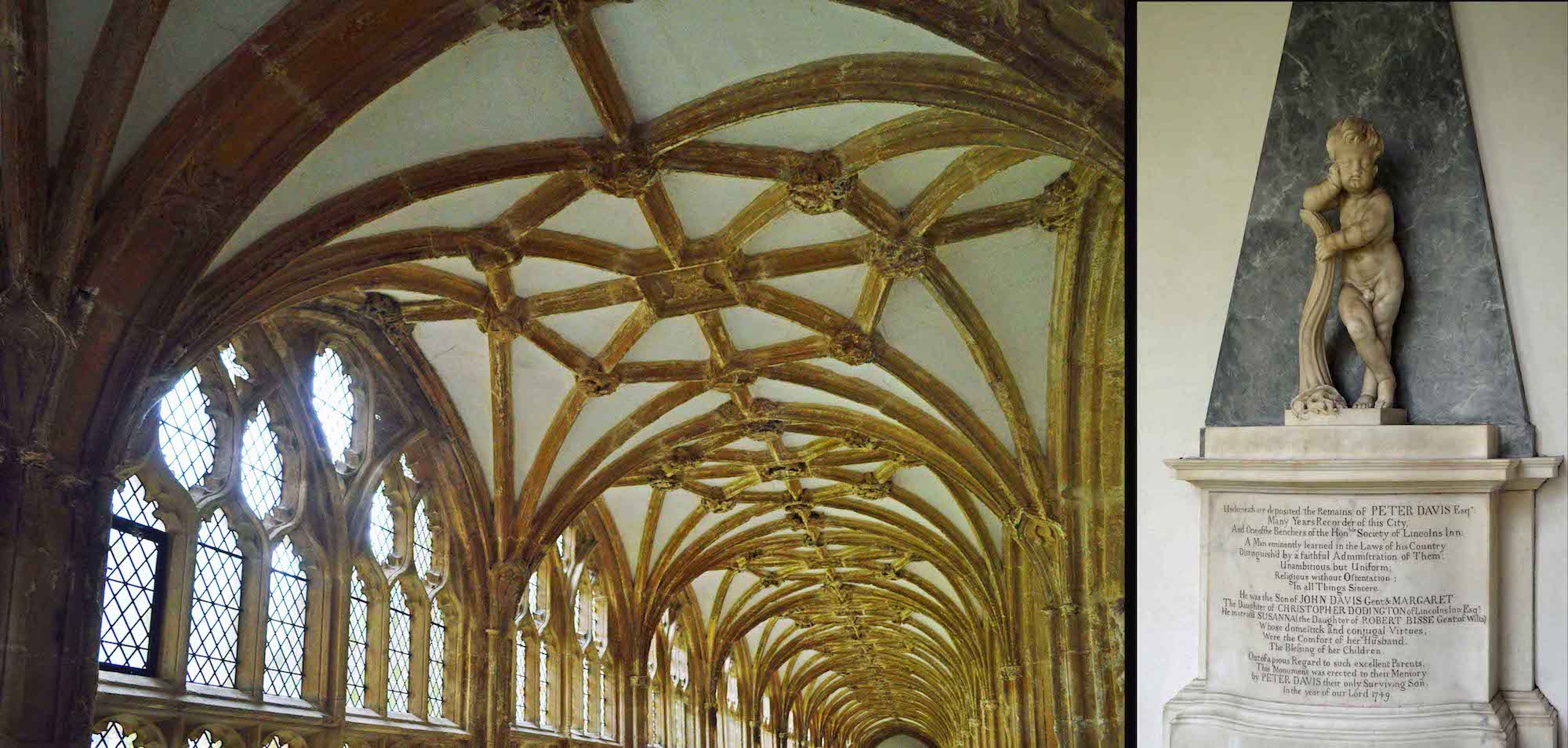

15. WEST CLOISTER – AGAIN!

We return to the West cloister, and walk back in a Southerly direction. The wall on our right is lined with plaques and memorial tablets, and there is a large monument on the wall ahead of us. This remembers George Hooper. George Hooper (1640 – 1727) was a learned and influential English High church cleric of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. He served as bishop of the Welsh diocese, St Asaph, and later for the diocese of Bath and Wells, as well as chaplain to members of the royal family.

16. SOUTH CLOISTER

So along the South cloister ... . The windows are plain lattice in style, and the wall to our right again has various monuments. These were removed from the Cathedral in the mid-nineteenth century by Dean Goodenough and placed here.

17. SOUTH CLOISTER VAULTING

The cloisters are simple in their decoration, but the vaulting is interesting with a linked series of octagons. • After the 1665 destruction, restoration of the Cathedral began again twenty years later under Bishop Thomas Ken. There has been continuous maintenance since. In 1933 the Friends of Wells Cathedral were formed to support the Cathedral’s chapter in the maintenance of the fabric, life and work of the cathedral. The late 20th century saw an extensive restoration programme, particularly of the West front, stained glass, and Jesse Tree window.

18. EAST CLOISTER

We arrive at the Southeast corner of the cloisters. The old door shown at left, guarded by St Andrew, once led to the Bishop’s Palace. The central view looks along the cloister towards this door. We are about to escape through the open door at left. The final view shows the cloister, looking North from the South end.

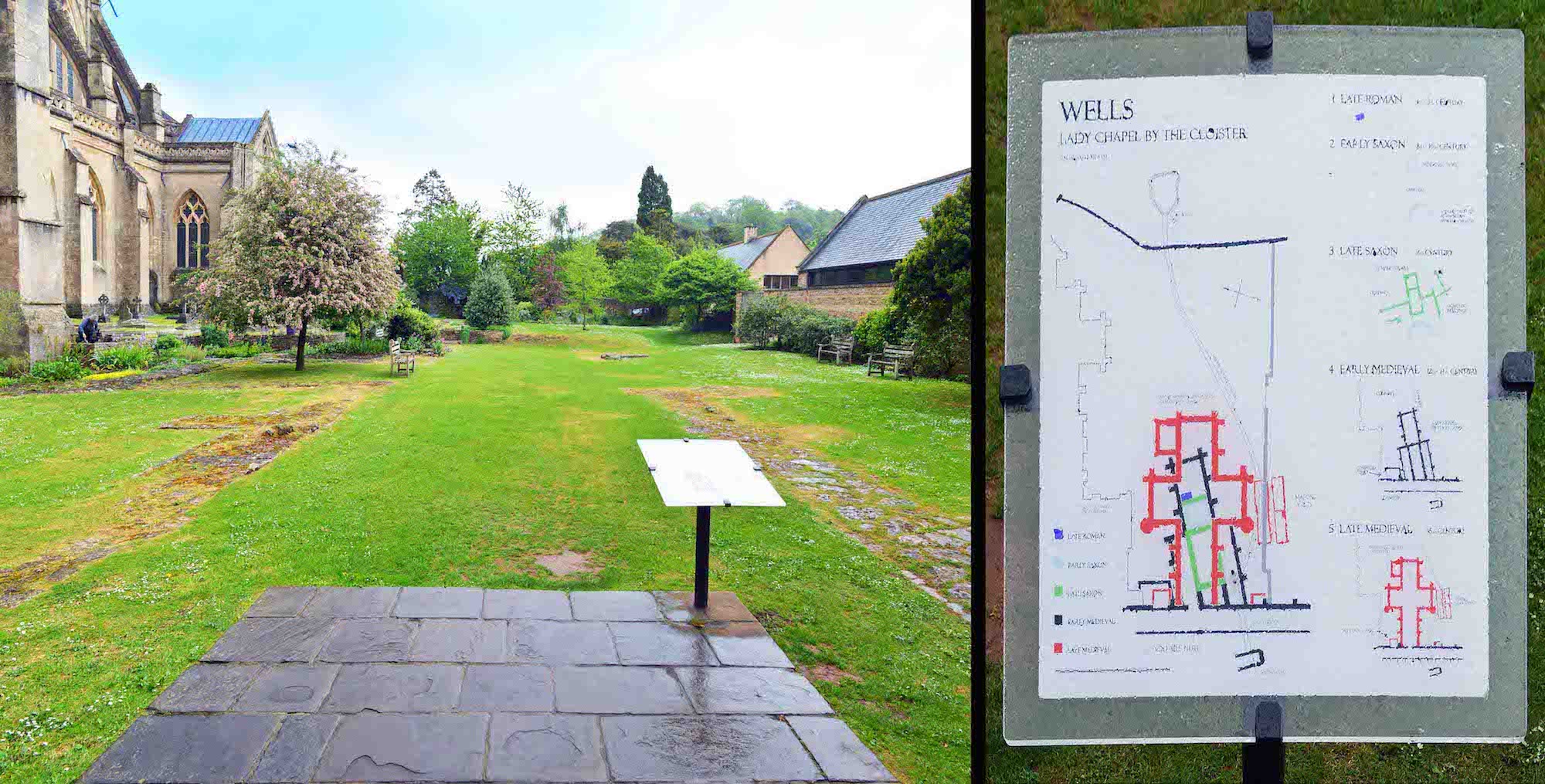

19. OLD LADY CHAPEL

Leaving the cloisters, we step out into the Camery Garden – an expansive area of lawn with the Cathedral on our left. Old foundations are visible in the lawned area. The plaque shows that several versions of a Lady Chapel were built here, before the present Lady Chapel was built at the East end of the Cathedral.

20. SOUTHERN VIEW

From the Camery lawned area we get great views of the central tower, South transept, quire, retroquire, and Lady Chapel. While there is one obvious join in the construction, the Cathedral has a pleasing uniformity of style, often not found in other cathedrals.