York Minster stands to the immediate northwest of the City of York. It is cruciform in shape with an attached chapter house at top right. It is oriented with its sanctuary almost exactly geographically east, so liturgical and geographical directions coincide here. There is a large central tower, and two smaller towers at the Western end. PLAN

2. NORTHWESTERN TOWER

We follow our usual practice and walk around the Cathedral in a clockwise direction. • The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, commonly known as York Minster, is the cathedral of York, England, and is one of the largest of its kind in Northern Europe.

3. NORTH NAVE

There is a pleasant lawned area to the North of the Cathedral. Also the inevitable signs of renovation work! The Minster has a very wide Decorated Gothic nave. • It is the seat of the Archbishop of York, the second-highest office of the Church of England, and is the mother church for the Diocese of York and the Province of York.

4. CENTRAL TOWER

The central tower serves as a lantern tower, allowing some light in over the crossing. • York Minster is run by a dean and chapter. The title ‘minster’ is attributed to churches established in the Anglo-Saxon period as missionary teaching churches, and serves now as an honorific title.

5. NORTH TRANSEPT

The North transept has an unusual set of lancet windows known as ‘the Five Sisters’. Each lancet of this window is over 52 feet (16 m) high. The upper windows are also visible from inside the Cathedral. • Services in the Minster are sometimes regarded as at the High Church or Anglo-Catholic end of the Anglican continuum.

6. NORTHEAST VIEW

As we have seen, a link branches from the Eastern corner of the North transept, leading to the chapter house. This view looks back past the link to the Western towers. • York has had a verifiable Christian presence from the 4th century. However, there is circumstantial evidence pointing to much earlier Christian involvement.

7. TOWARDS THE CHAPTER HOUSE

In 741 the Church of the time was destroyed in a fire. It was rebuilt as a more impressive structure containing thirty altars. The Church and the entire area then passed through the hands of numerous invaders, and its history is obscure until the 10th century.

8. THE NORTHEASTERN CORNER

We leave the pleasant grassy sward of Dean’s Park and walk along the Minster Yard access road past the chapter house. • Continuing the Cathedral history, there was a series of Benedictine archbishops, including Saint Oswald of Worcester, Wulfstan, and Ealdred who travelled to Westminster to crown William in 1066. Ealdred died in 1069 and was buried in the Church.

9. NORTH QUIRE AISLE

From across the access road we obtain a nice view of the Quire and East End, and chapter house. • The Church was damaged in 1069 during William the Conqueror’s harrying of the North, but the first Norman archbishop, Thomas of Bayeux, arriving in 1070, organised repairs. The Danes destroyed the Church in 1075, but it was again rebuilt in Norman style from 1080.

10. CHAPTER HOUSE

The chapter house is built in Gothic style. Like the chapter houses of Salisbury and Wells Cathedrals it is octagonal in shape. • The new Church was 111 m (364 ft) long and rendered in white and red lines. It was damaged by fire in 1137 but was soon repaired. The quire and crypt were remodelled in 1154, and a new chapel was built, all in the Norman style.

11. EAST END

The Great East Window was finished in 1408, and is the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the world. There are many empty niches in this wall where sculpted figures might have been placed. • The Gothic style in cathedrals had arrived in the mid 12th century. Walter de Gray was made archbishop in 1215 and ordered the construction of a Gothic structure to compare to Canterbury; building began in 1220.

12. EAST WALL FEATURES

Sculpted figures peer out from the otherwise empty niches level with the sill of the East window. Two of these are shown here. • The North and South transepts were the first new structures; completed in the 1250s, both were built in the Early English Gothic style but had markedly different wall elevations. A substantial central tower was also completed, with a wooden spire. Building continued into the 15th century.

13. STRIP OF HEADS

A further strip of heads can be seen below the East window, showing varying degrees of weathering. • The chapter house was begun in the 1260s and was completed before 1296. The wide nave was constructed from the 1280s on the Norman foundations. The outer roof was completed in the 1330s, but the vaulting was not finished until 1360.

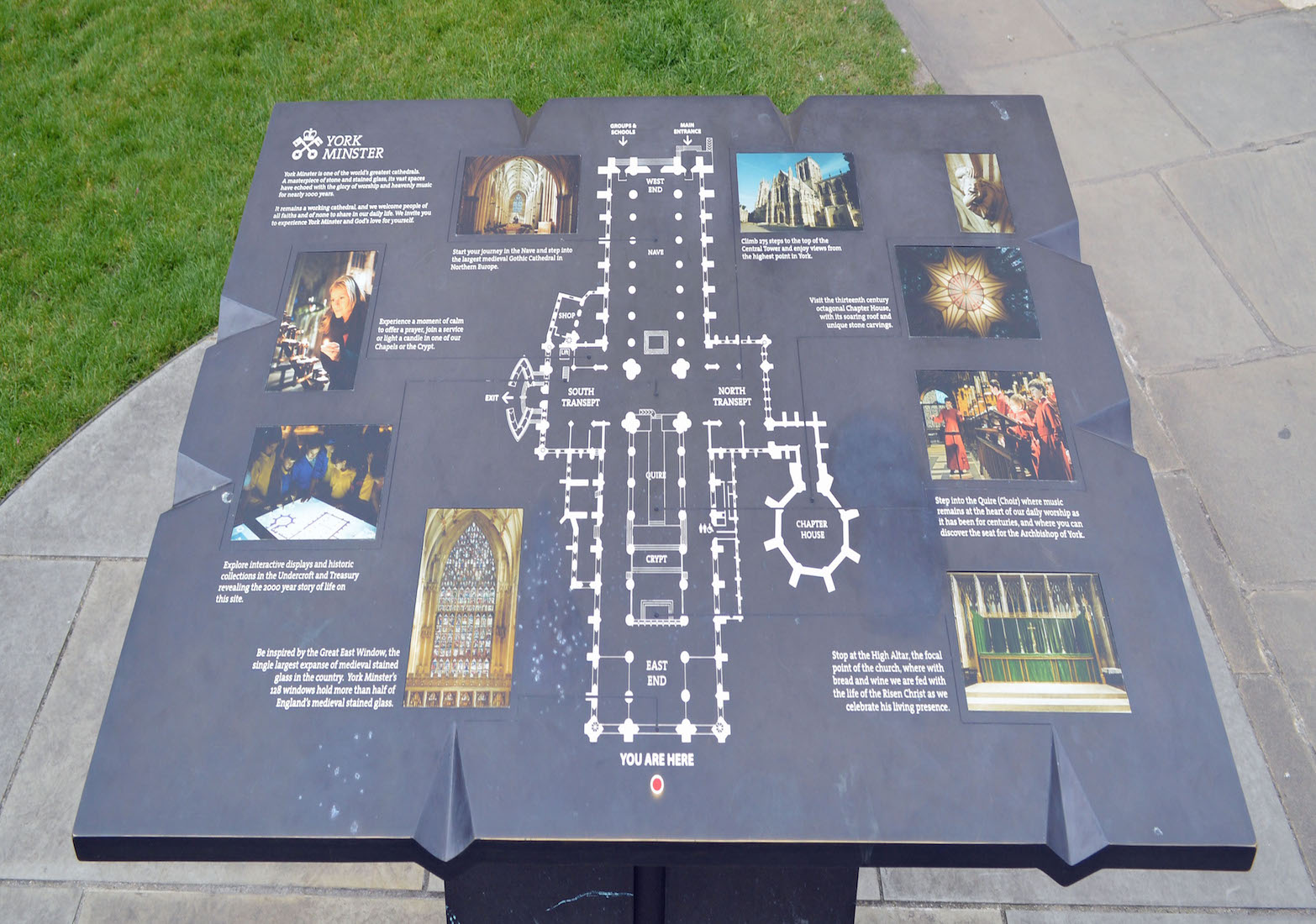

14. CATHEDRAL PLAN

Near the East end is an attractive Minster plan with photographs. As cathedrals go, the York plan is fairly straightforward. • After 1360, construction moved on to the Eastern arm and chapels, with the last Norman structure, the quire, being demolished in the 1390s. Work here finished around 1405.

15. NORTHEAST CORNER

The buttresses along the wall here are capped by large heavy pinnacles, designed to redirect the outward forces on the walls down the buttresses. • In 1407 the central tower collapsed; the piers were then reinforced, and a new tower was built from 1420. The Western towers were added between 1433 and 1472. The Cathedral was declared complete and consecrated in 1472.

16. WORKSHOP

A stone masons’ workshop is tucked into the side of the Cathedral here. I watched as two men carefully shaped Cathedral blocks, reflecting how good it is that the old skills are still being used. Then I thought about the million weathering stones in the Minster ... !

17. SOUTH TRANSEPT AND CENTRAL TOWER

In 1967 a survey revealed the building, and in particular the central tower, was close to collapse. £2,000,000 was raised and spent by 1972 to reinforce and strengthen the building foundations and roof. During the excavations that were carried out, remains of the North corner of the Roman Principia (headquarters of the Roman fort, Eboracum) were found under the South transept.

18. SOUTH TRANSEPT

On 9 July 1984, a fire believed to have been caused by a lightning strike destroyed the roof in the south transept. Huge amounts of water were needed to provide jets to play on the roof timbers and protect the rose window. Around £2.5 million was spent on repairs. The glass in the rose window dates from about 1500 and commemorates the union of the royal houses of York and Lancaster.

19. ROSE WINDOW

Peter Gibson reports that after the 1984 fire, the glass in the rose window was cracked into something like 40,000 pieces. To stop the cracked glass falling apart as the window panels were removed, clear plastic was stuck onto the outside. So over three weeks, as the team removed the 73 panels, all the glass was secure.

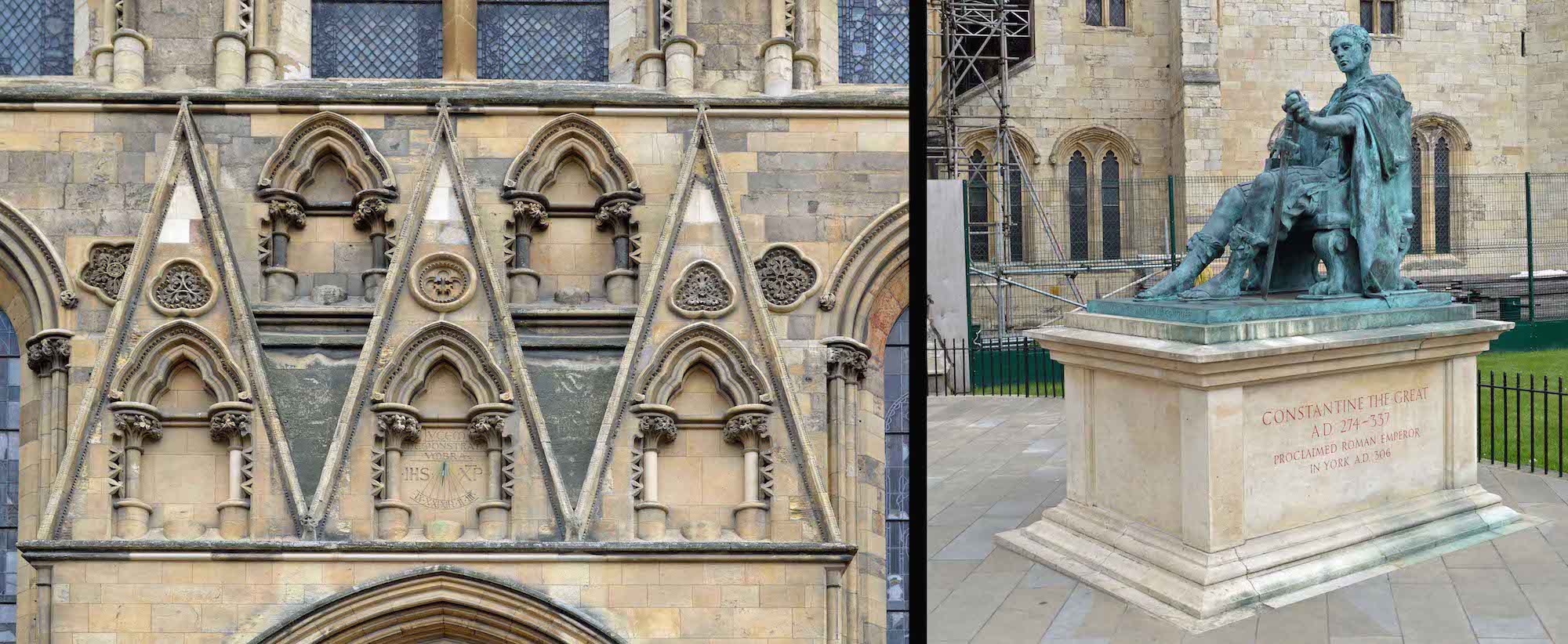

20. TRANSEPT DETAIL AND CONSTANTINE THE GREAT

The statue of Constantine the Great is outside the South transept. Constantine came to Britain in 305, and soldiers in York immediately proclaimed him their leader. After nearly 80 years of political fragmentation, Constantine united the whole of the Roman Empire under one ruler. By 324 he was sole emperor, restoring stability and security to the Roman world.