Hereford Cathedral is the cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Hereford in Hereford, England. Its most famous treasure is Mappa Mundi, a medieval map of the world created around 1300 by Richard of Holdingham. The map is listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. The cathedral is a Grade I listed building. The site of the cathedral became a place of worship in the 8th century or earlier although the oldest part of the current building, the bishop’s chapel, dates to the 11th century. PLAN

2. NORTH SIDE

We begin at the Northwest corner, and make our way around the Cathedral in a clockwise direction. The Cathedral is set in a lovely lawned area, and these are views along the North side. ••• The Cathedral is dedicated to two saints, St Mary the Virgin and St Ethelbert the King. The latter was beheaded by Offa, King of Mercia in the year 794. Offa had consented to give his daughter to Ethelbert in marriage: historians do not know why he changed his mind and deprived him of his head.

3. ELGAR’S VIEW

Sir Edward Elgar pauses to view the Cathedral. Elgar lived in Hereford for several years and was associated with the Cathedral for most of his life through his links with the Three Choirs Festival. Notice the stonecutters’ yard tucked in by the North transept.

4. STONECUTTERS’ YARD

The tools of the modern stonemason have changed very little since the medieval period. Stonemasons from Capps & Capps, who have worked extensively on Hereford Cathedral, still use simple metal chisels, lump-hammers and pairs of compasses to carve the blocks, the only difference today being that often the chisels are tipped with titanium which makes them considerably more robust than those of a medieval mason.

5. FROM THE NORTHEAST

We continue our walk around the Cathedral. ••• The execution, or murder, of King Offa is said to have taken place at Sutton, four miles (6 km) from Hereford, with Ethelbert’s body brought to the site of the modern Cathedral by ‘a pious monk’. He was buried at the site of the Cathedral. At Ethelbert’s tomb miracles were said to have occurred, and in the next century (about 830) Milfrid, a Mercian nobleman, was so moved by the tales of these marvels as to rebuild in stone the little church which stood there, and to dedicate it to the sainted king.

6. EAST WALL

The Cathedral East wall is the East wall of the Lady Chapel. ••• Before 830, Hereford had become the seat of a bishopric. It is said to have been the centre of a diocese as early as the 670s when Theodore of Tarsus, Archbishop of Canterbury, divided the Mercian diocese of Lichfield. The cathedral of stone, which Milfrid raised, stood for some 200 years, and then, in the reign of Edward the Confessor, it was altered. The new church had only a short life, for it was plundered and burnt in 1056 by a combined force of Welsh and Irish under Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, the Welsh prince; it was not, however, destroyed until its custodians had offered vigorous resistance, in which seven of the canons were killed.

7. SOUTHEAST VIEW

Of Interest here is the Audley Chantry, extending from the side of the Lady Chapel. ••• Hereford Cathedral remained in a state of ruin until Robert of Lorraine was consecrated to the see (made a bishop) in 1079 and undertook its reconstruction. His work was carried on by the later Bishop Reynelm, who also reorganised the college of secular canons attached to the Cathedral. Reynelm died in 1115, and it was only under his third successor, Robert de Betun, who was Bishop from 1131 to 1148, that the church was brought to completion.

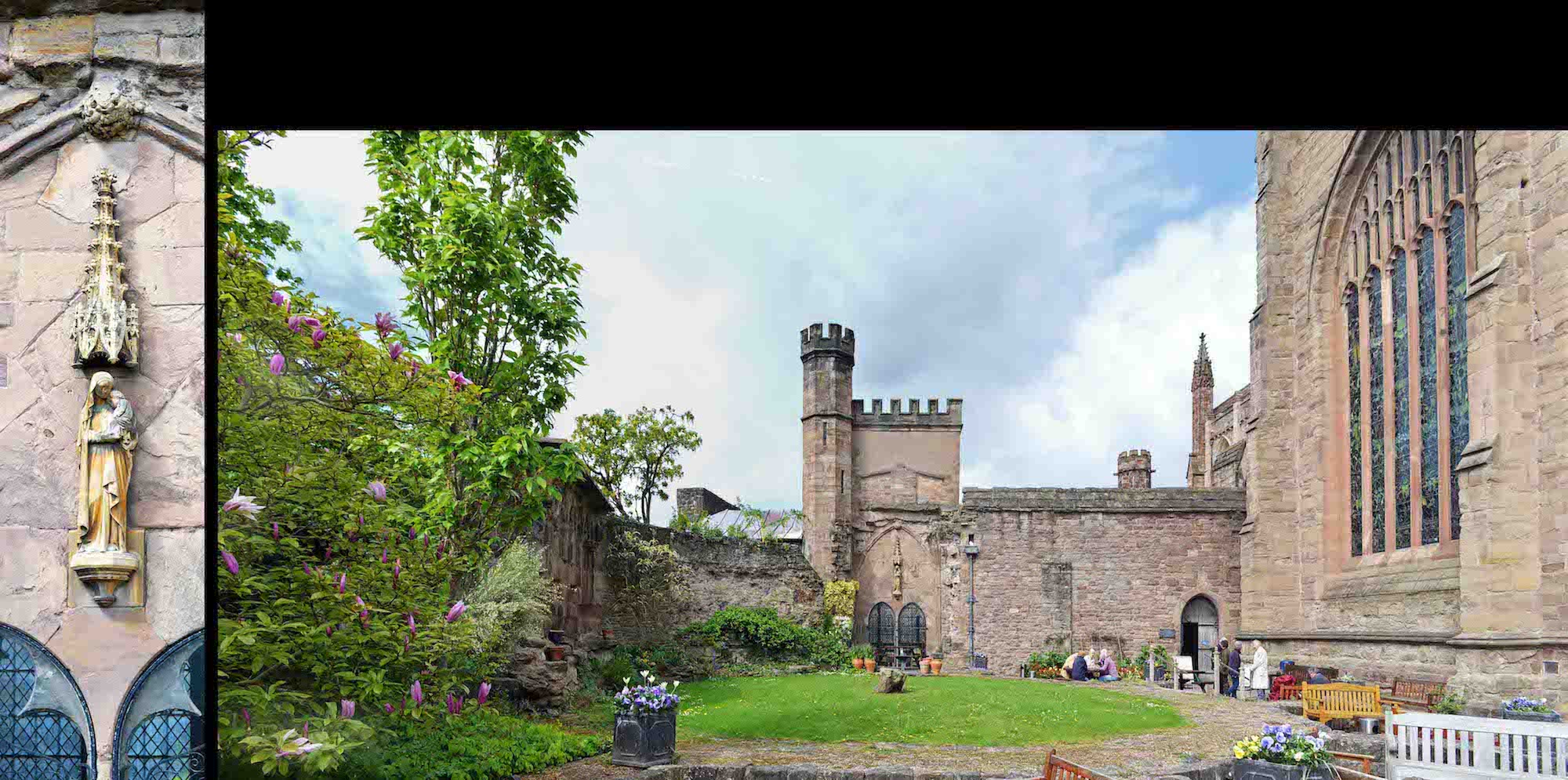

8. TO THE CHAPTER HOUSE GARDEN

Our path is now partially blocked by a covered walkway, St John’s Walk, which leads from an entry to the Southeast transept. Later we shall enter the Cathedral this way. The walkway shields the site of the old chapter house where there is now a very attractive garden. ••• Of the old Norman church, the suriving parts are the nave arcade, part of the choir, the choir aisle, the South transept, and the crossing arches. Scarcely 50 years after its completion William de Vere, who occupied the see 1186 – 1199, altered the East end by constructing a retro-choir or processional path and a Lady Chapel; the latter was rebuilt not long afterwards (1226 – 1246), in the Early English style – with a crypt beneath.

9. IN THE GARDEN

Time for a short relaxation in the garden! Unfortunately for me, it is too early for coffee ... . ••• Around 1250 the clerestory, and probably the vaulting of the choir, were rebuilt, having been damaged by the settling of the central tower. Under Peter of Aigueblanche (bishop 1240–68), one of Henry III’s foreign favourites, the rebuilding of the North transept was begun, being completed later in the same century by Swin(e)field, who also built the aisles of the nave and eastern transept.

10. SOUTH TRANSEPT

The South transept and adjacent Cathedral wall face on to the Chapter House Garden. ••• One of the most notable of the pre-reformation Bishops of Hereford, who left his mark upon the cathedral and the diocese, was Peter of Aigueblanche, also known as Aquablanca, who rebuilt the North transept. Aquablanca was undoubtedly a man of energy and resource;. However, although he lavished money upon the Cathedral and made a handsome bequest to the poor, it cannot be pretended that his qualifications for the office to which Henry III appointed him included piety. He was a nepotist who occasionally practised gross fraud.

11. THROUGH PAST THE SHOP

We resist the temptation to investigate the gift shop and the cafeteria and proceed through into the old Cloister Garden – another very attractive space. ••• When Prince Edward came to Hereford to deal with Llywelyn the Great of Gwynedd, Aquablanca was away in Ireland on a tithe-collecting expedition, and the dean and canons were also absent. Not long after Aquablanca's return, which was probably expedited by the stern rebuke which the King administered, he and all his relatives from Savoy were seized within the Cathedral by a party of barons, who deprived him of the money which he had extorted from the Irish.

12. CLOISTER GARDENS

From the Lady Arbour Cloister Gardens there are good views of the Cathedral tower and the South wall of the nave. Notice the seat with the grey plaque behind. Hereford Cathedral houses 10 bells 140 ft (43 m) high in the tower. The tenor bell weighs 34 cwt (1.7 tonnes). The oldest bell in the Cathedral is the sixth which dates back to the 13th century. The bells are sometimes known as the ‘Grand Old Lady’ as they are a unique ring of bells.

13. SEAT MEMORIAL

The memorial is for eight girls who died in a fire in 1916 while raising funds for the War effort. The nearby pavement slab is in memorial of Allan Leonard Lewis who is curiously given two dates in 1918, days apart. ••• In the first half of the 14th century the rebuilding of the central tower was carried out. At about the same time the chapter house and its vestibule were built, then Thomas Trevenant, who was bishop from 1389 to 1404, rebuilt the south end and groining of the great transept. Around the middle of the 15th century a tower was added to the western end of the nave, and in the second half of this century bishops John Stanberry and Edmund Audley built their chantries.

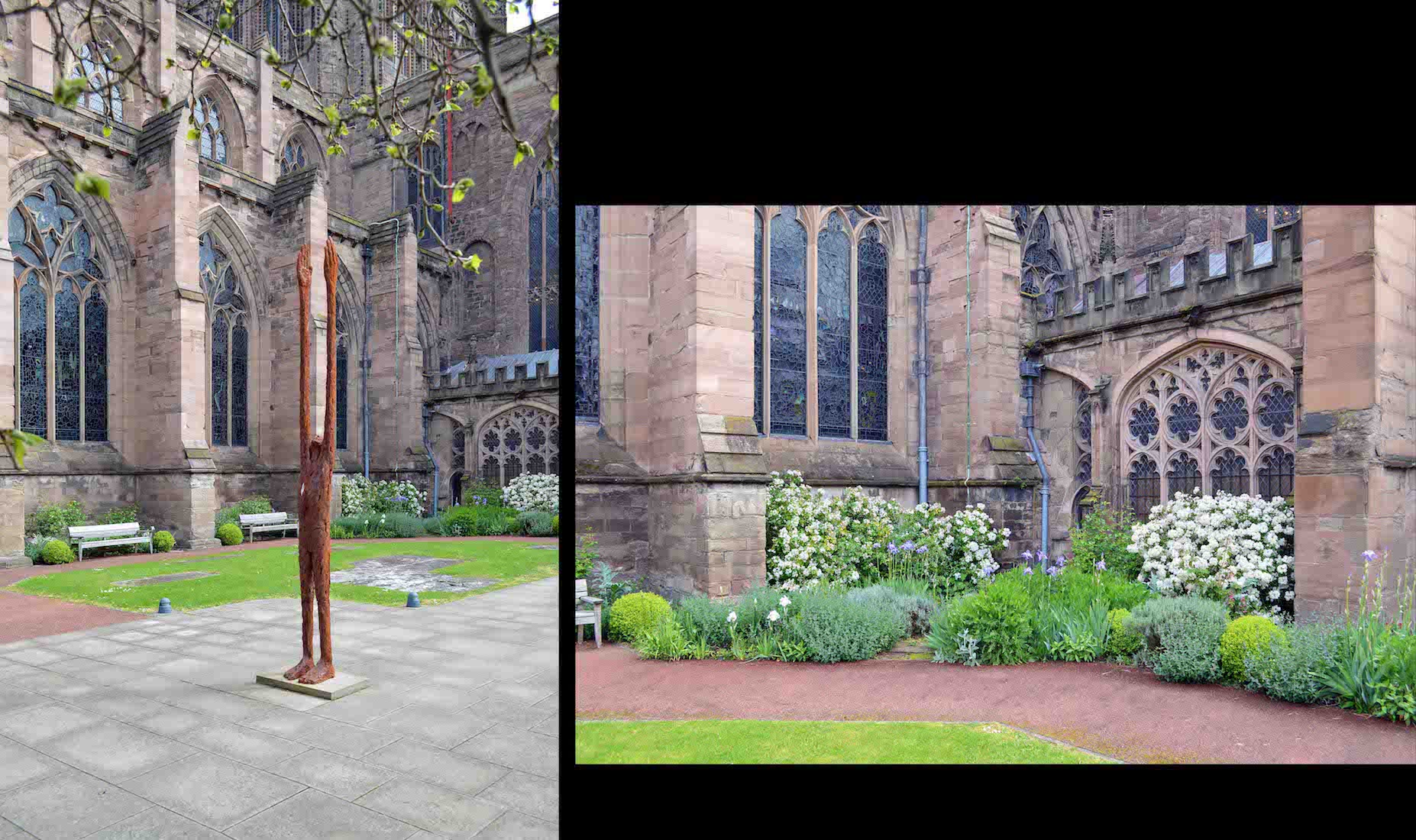

14. GARDEN SCULPTURE

The central sculpture is cast in bronze resin and called ‘Beyond Limitations’. It is by John O’Connor, who studied at the Sculpture Academy in London for four years, before going on to teach sculpture, moulding and casting. It was placed in the Lady Arbour Cloister Gardens in 2013. ••• Later bishops Richard Mayew and Booth, who between them ruled the diocese from 1504 to 1535, made the last additions to the Cathedral by erecting the North porch, now forming the principal Northern entrance. The building of the present edifice therefore extended over a period of 440 years.

15. CLOISTER GARDEN

The Cloister Gardens are bounded by the Cathedral nave to the North, the gift shop and cafeteria to the East, and the wing containing the Museum, Mappa Mundi and Chained Library to the South (shown here). ••• Thomas de Cantilupe was the next but one Bishop of Hereford after Aquablanca. He had faults not uncommon in men who held high ecclesiastical office in his day, however he was a strenuous administrator of his see, and an unbending champion of its rights.

16. GARDEN VIEW

A gateway at the West end of the Cloister Gardens opens to a path past the central sculpture. Just inside is a paving slab with the letters VR remembering a visit by Queen Victoria. We move around to the West wall of the Cathedral.

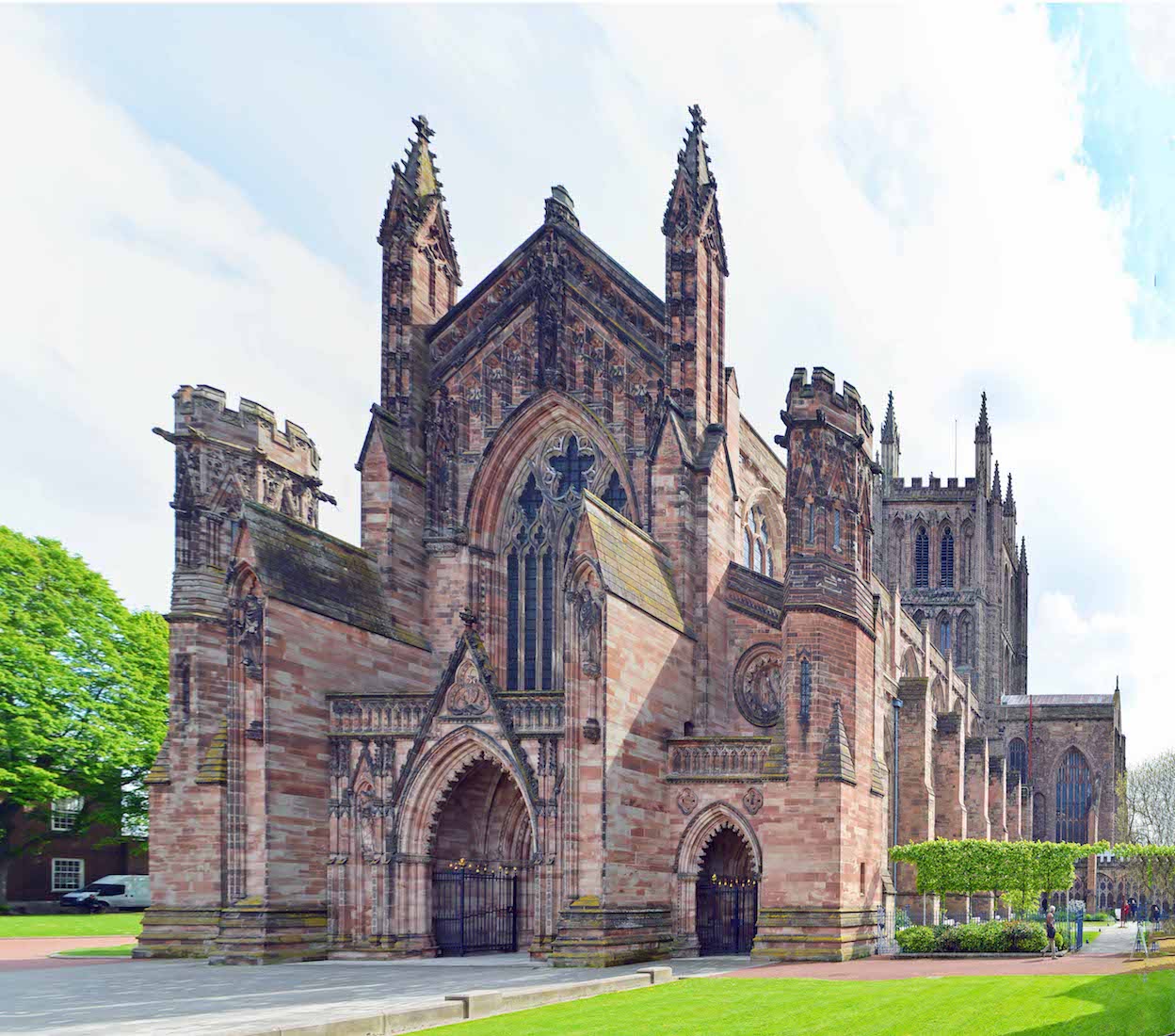

17. WEST WALL

••• On Easter Monday, 1786, the greatest disaster in the history of the Cathedral took place. The West tower fell, creating a ruin of the whole of the West front and at least one part of the nave. The tower, which was not replaced, had a general resemblance to the central tower; both were profusely covered with ball-flower ornaments, and both terminated in leaden spires. James Wyatt was called in to repair the damage. Instead of just repairing, he made alterations which were (and are) not universally popular.

18. DETAIL OF WEST WALL

If we look closely at the West wall we see that there are various standing figures, and a couple of interesting looking roundels. The gable above the West doors contains a trefoil figure with a shield inside. ••• In 1841 restoration work was begun, instigated by Dean Merewether, and was carried out by Lewis Nockalls Cottingham and his son, Nockalls. The lantern of the central tower was strengthened and exposed to view, and much work was done in the nave and to the exterior of the Lady Chapel.

19. WEST WALL ROUNDELS

Each of the West wall roundels contains a scene. Since the Cathedral is dedicated to St Mary the Virgin and St Ethelbert the King who was beheaded, it seems likely that the roundels depict the trial and execution of King Ethelbert. ••• After the death of restorer Nockells, George Gilbert Scott was called in, and from that time the work of restoring the choir was performed continuously until 1863, when (on 30 June) the cathedral was reopened with solemn services.

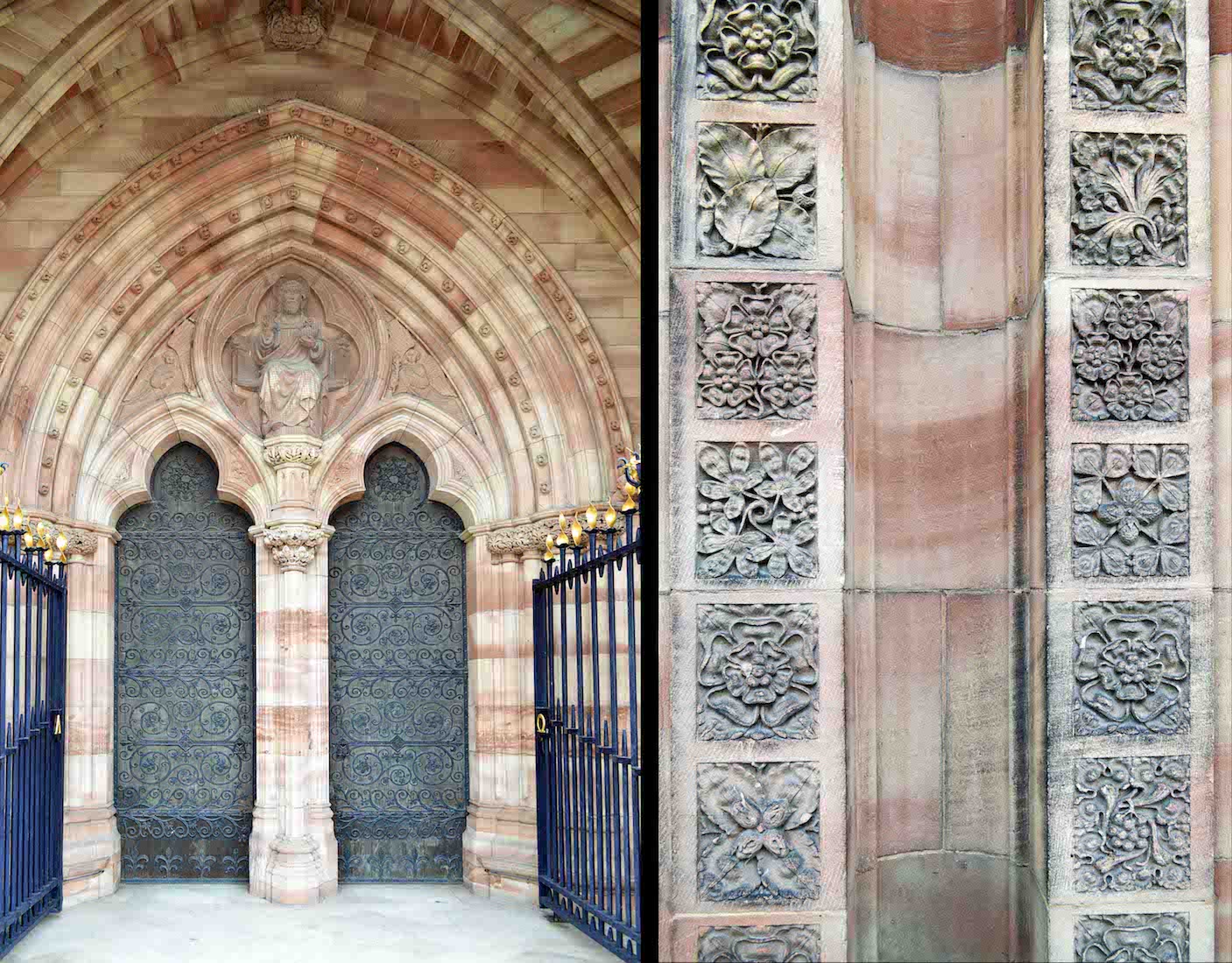

20. WEST DOORS

The arch above the Western doors contains an image of the Risen Christ bidding welcome to those who enter. The decorated masonry strips belong to one of four pairs of strips which adorn the entry panel of the West wall.