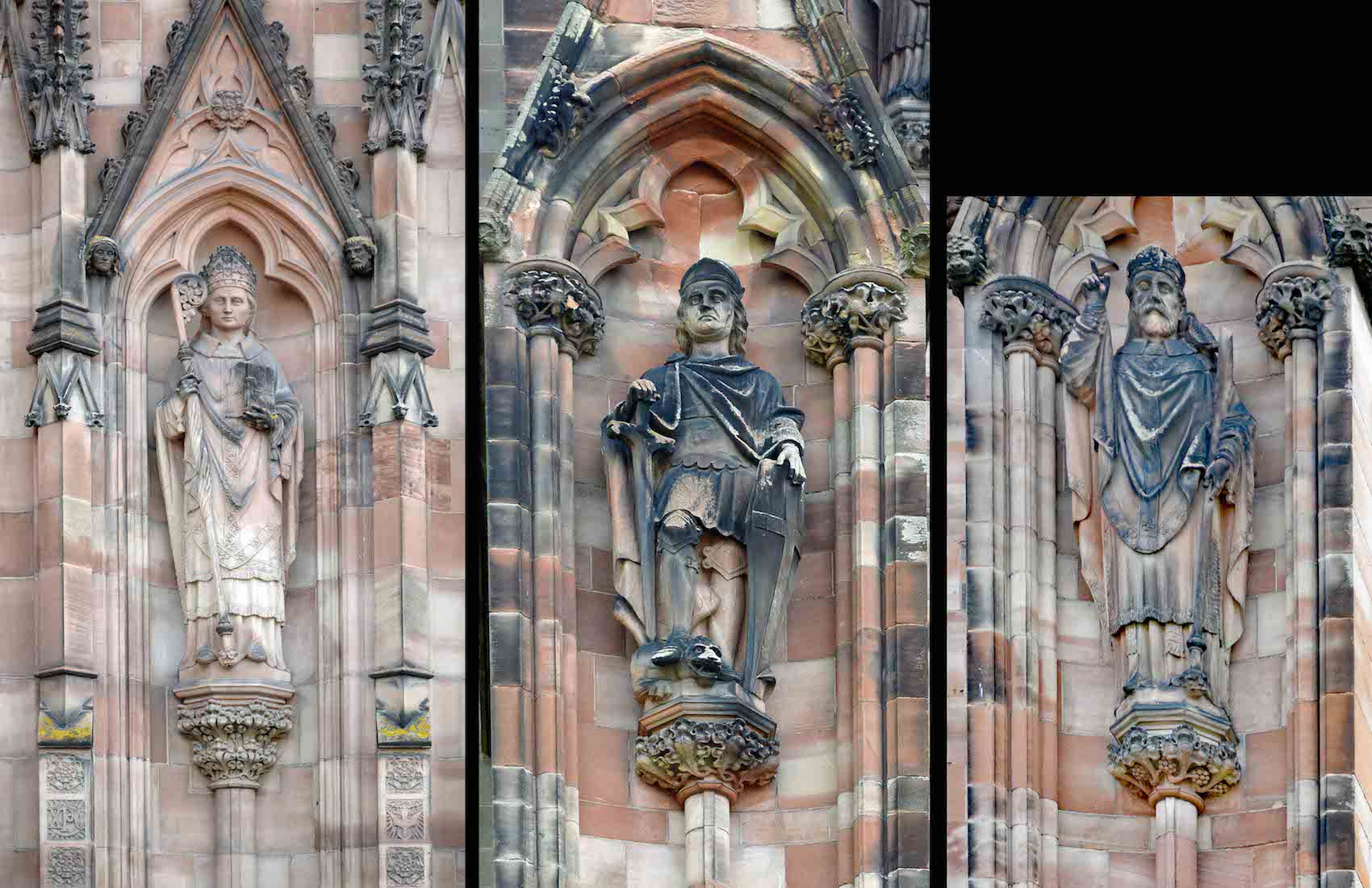

The West wall is not highly decorated, but there are various figures. Identification requires some inside knowledge! ••• Here are some measurements of the Cathedral: exterior length 342 feet (104 m); interior length 326 feet (99 m); nave length 158 feet (48 m); choir length 75 feet (23 m). The great transept length 146 feet (45 m) long; the East transept 110 feet (34 m). Nave and choir width including the aisles) 73 feet (22 m); nave height 64 feet (20 m) high; choir height 62½ feet. The lantern (within the tower) height 96 feet (29 m); the tower height 140½ feet, or with the pinnacles 165 feet (50 m). PLAN

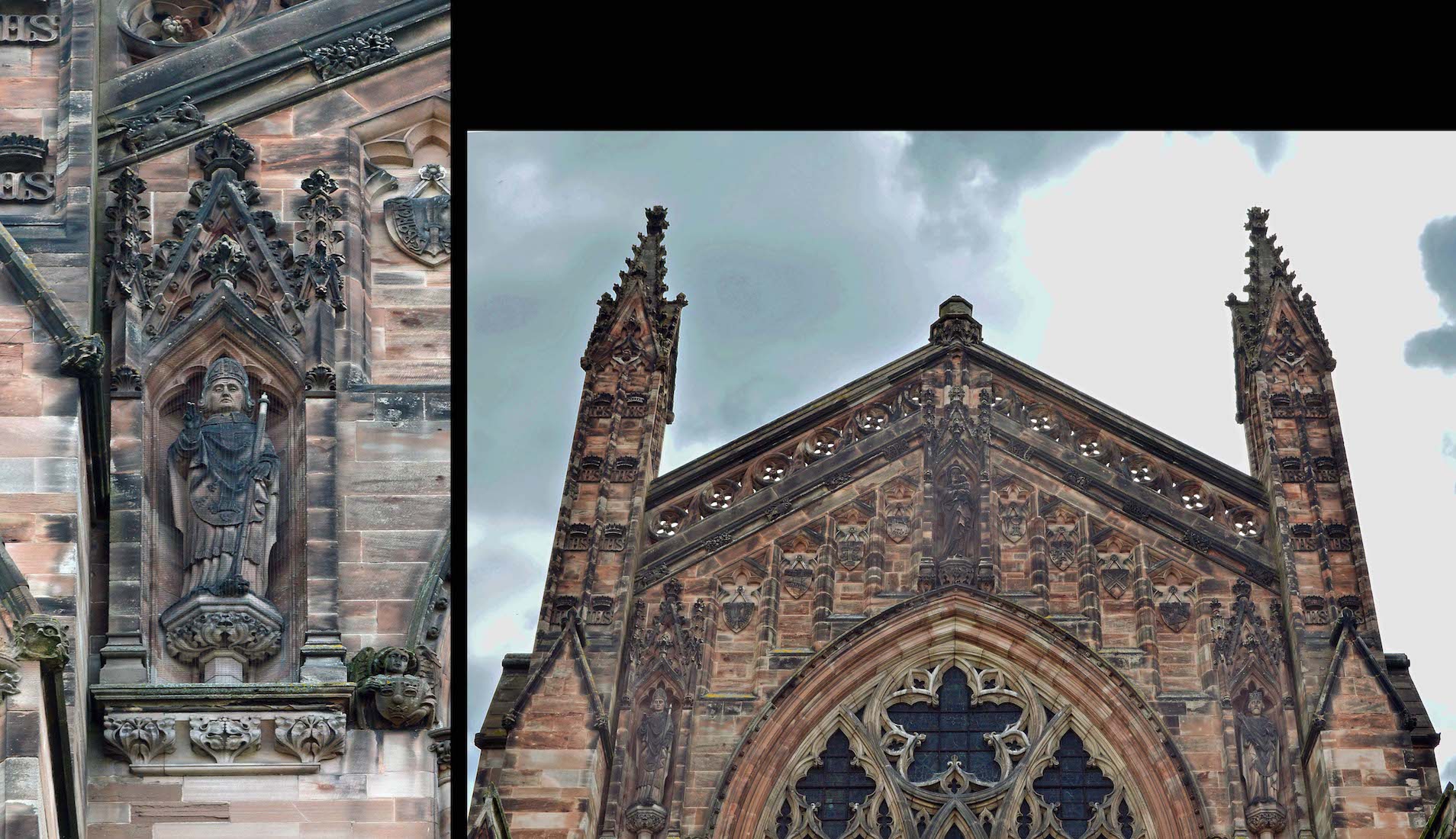

22. WEST GABLE

Similarly we can look up to the West gable with its associated figures ... .

23. FORECOURT APPLE TREE

An apple tree is depicted on the Western forecourt. The original sketch was inspired by the carol, ‘Jesus Christ the Apple Tree’. The six-metre diameter mosaic comprises 50m2 of natural stone paving. The masonry team spent a total of 500 man-hours processing and finishing the composite pieces, using modern hand tools for speed and efficiency and more traditional methods and techniques for the detailing.

24. MODEL CATHEDRAL AND SETTING

At the West end of the Cathedral is a three dimensional model of the Cathedral in its setting, set on a short concrete pillar. A plaque on the pillar acknowledges that this is part of the Cathedral Close project, and gives a list of those who contributed.

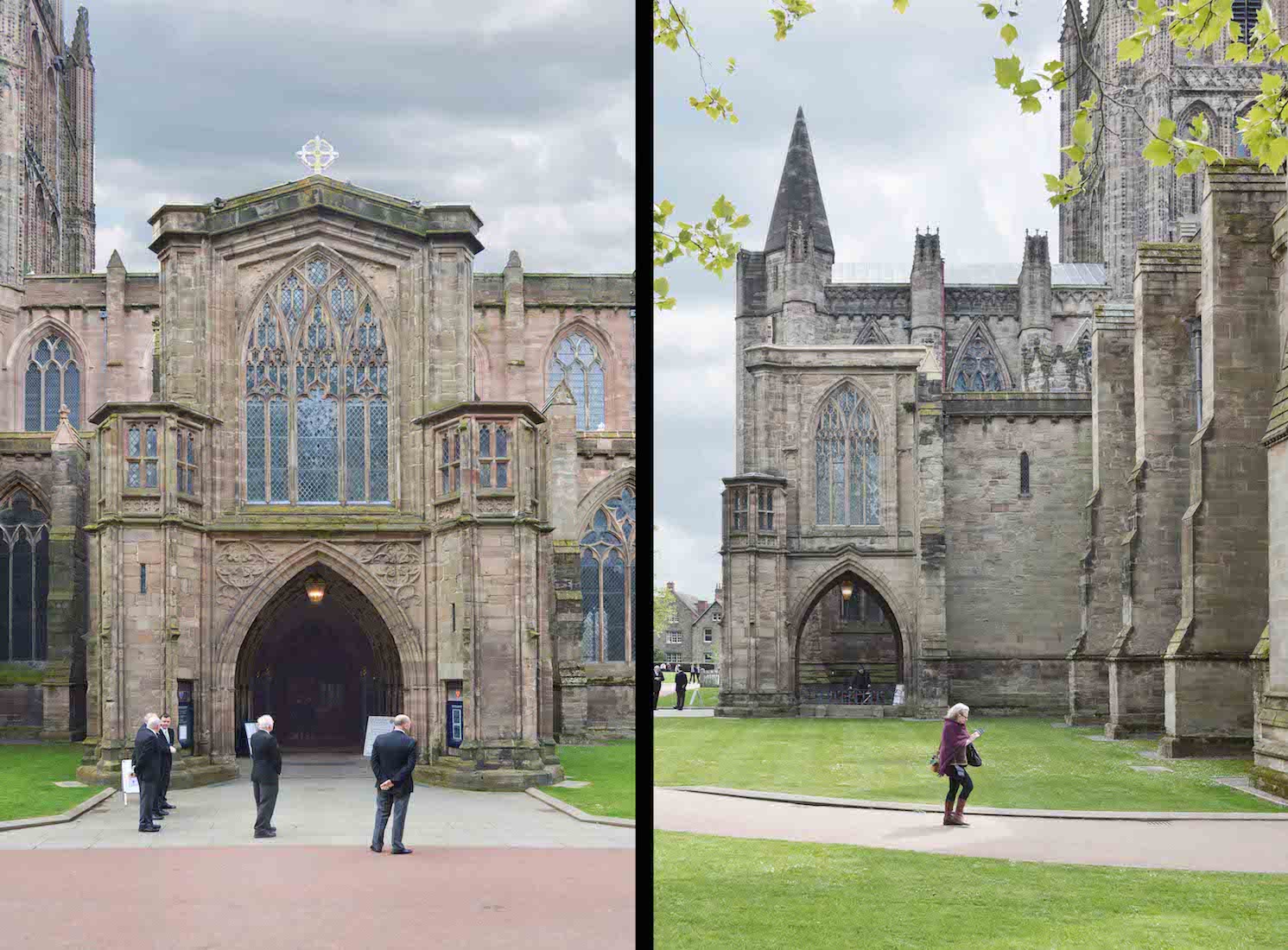

25. NORTH PORCH

Back to our starting point at the North porch. Unfortunately for us, there is a funeral being held here – part of cathedral life! ••• The porch was erected in a geometrical Perpendicular style by Bishop Booth in 1519, extending an earlier structure, integral with the body of the cathedral, of about 1300. The present porch is the most recent part of the Cathedral structure.

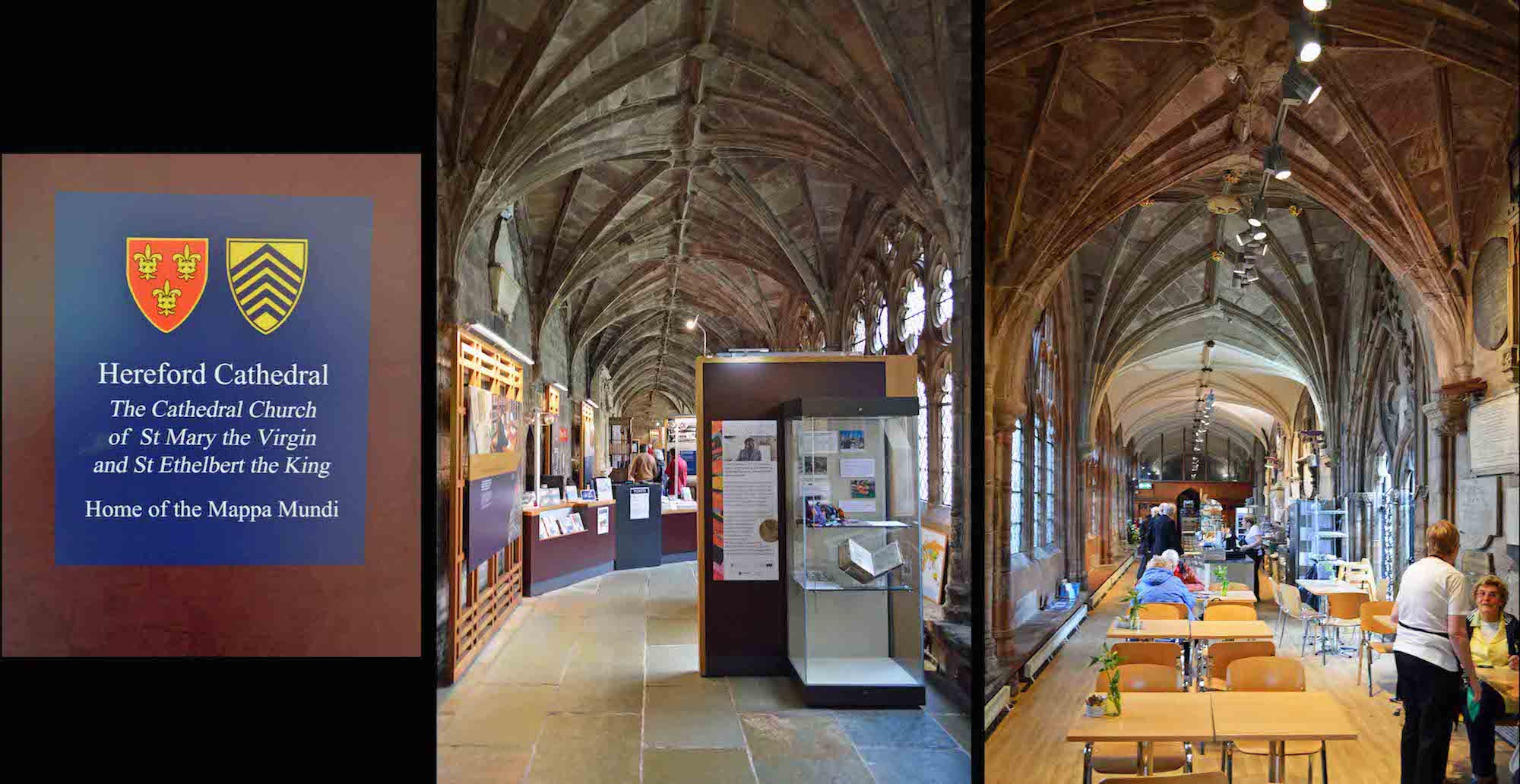

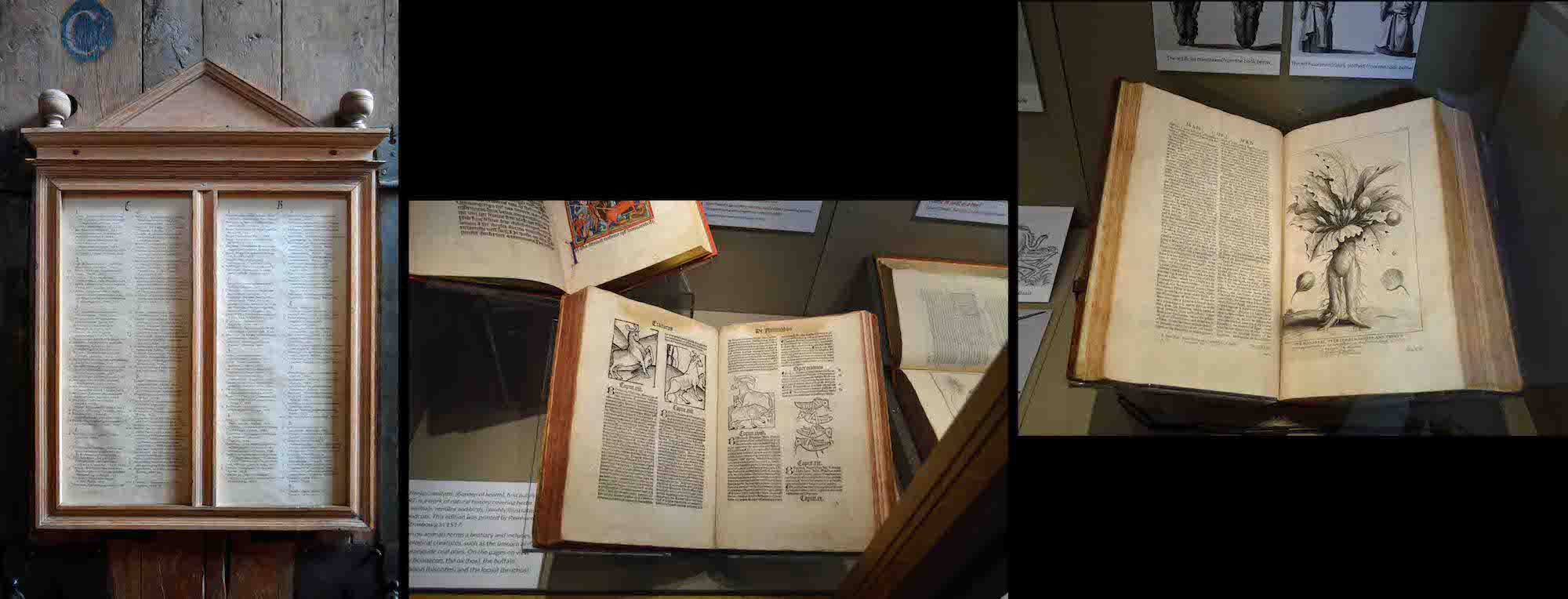

27. MUSEUM DISPLAY I

The hallway leading to the Mappa Mundi and the Chained Library is full of exhibits relating to early books and their printing. Here we have a very old illustrated book, a chest used in olden days for transporting books, and some explanation of the Chained Library.

28. MUSEUM DISPLAY II

Many book chests incorporated a carrying pole. Against the left wall is a small shelf illustrating the principles of the chained library. A directory on the outer support lists the material available, and there are some chained books which can be removed from the shelf and read (with difficulty!).

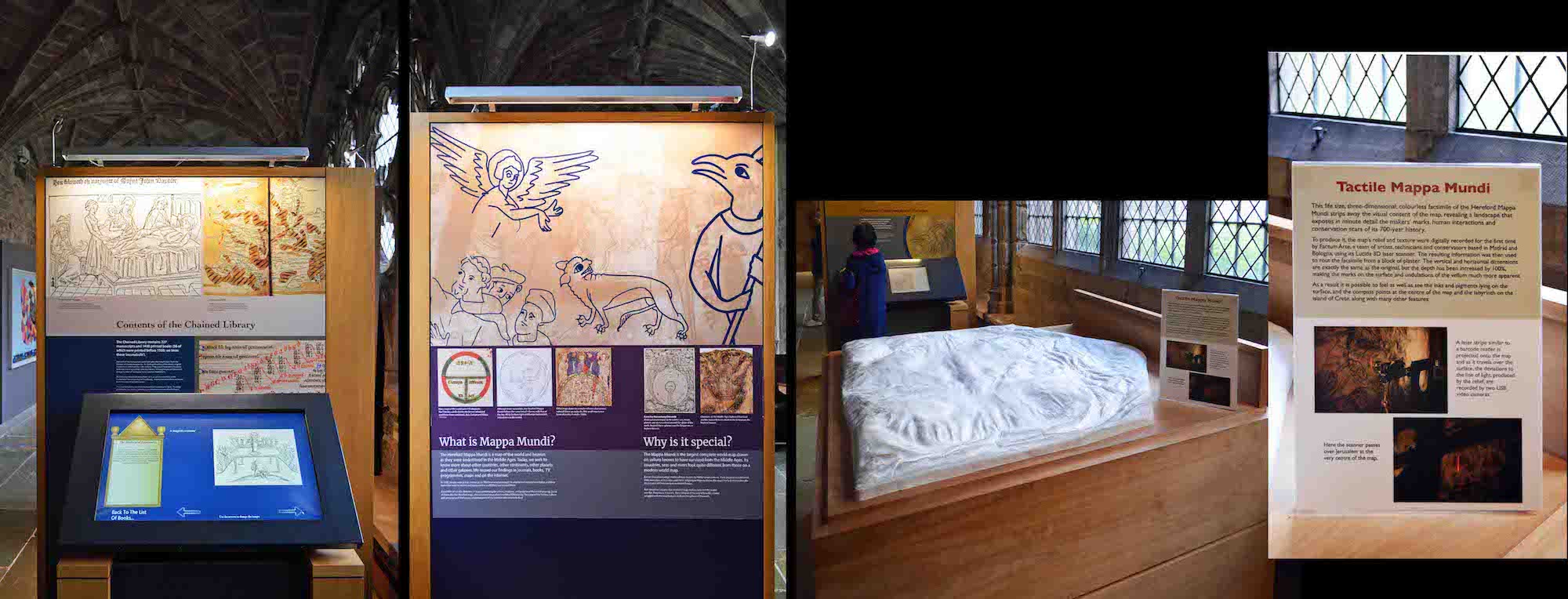

29. MUSEUM DISPLAY III

Here is detailed information on the Chained Libarary and the Mappa Mundi. There is also a ‘Tactile’ Mappa Mundi where all the visual information has been removed leaving makers’ marks, human interactions and conservation scars of its 700 year history..

30. MUSEUM DISPLAY IV

Next is information about the beasts and people illustrated on the Mappa Mundi, and yet another Book Chest.

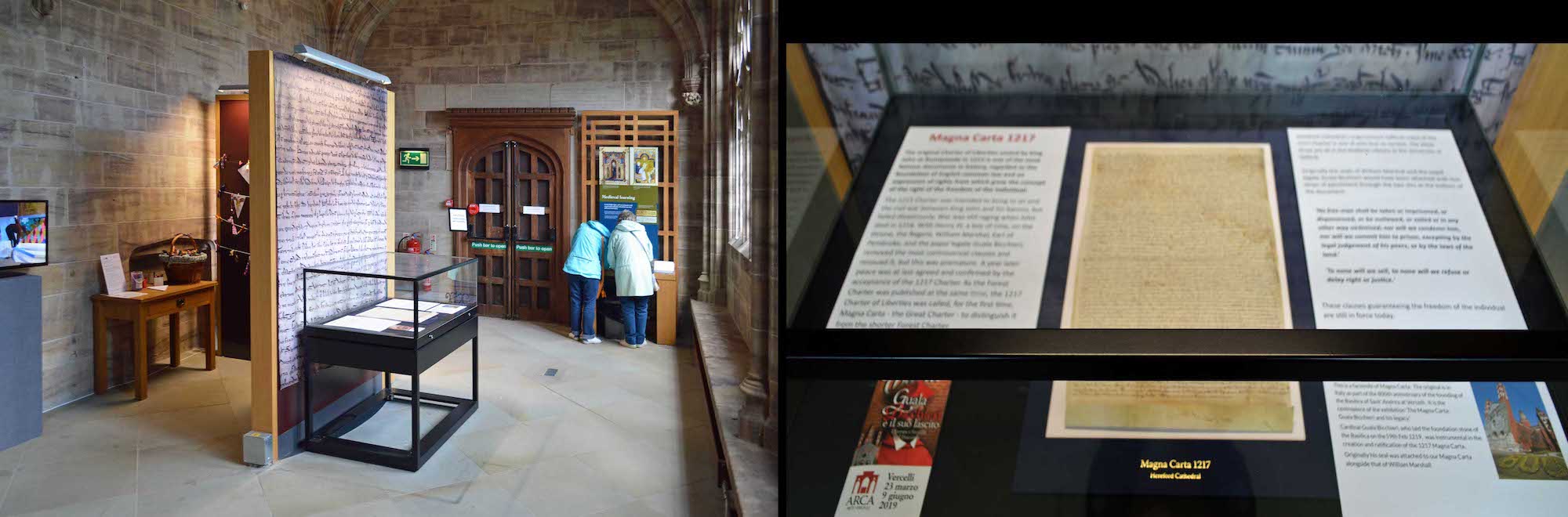

31. AROUND THE CORNER

At this point the museum hallway does a right hand turn. Ahead of us is a standing screen and cabinet display which turns out to be about the 1217 Magna Carta. Magna Carta (‘Great Charter’), is a charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. Four original copies survive, all held in England: two now at the British Library, one at Lincoln Cathedral, and one at Salisbury Cathedral. This is a slightly later copy or ‘exemplification’.

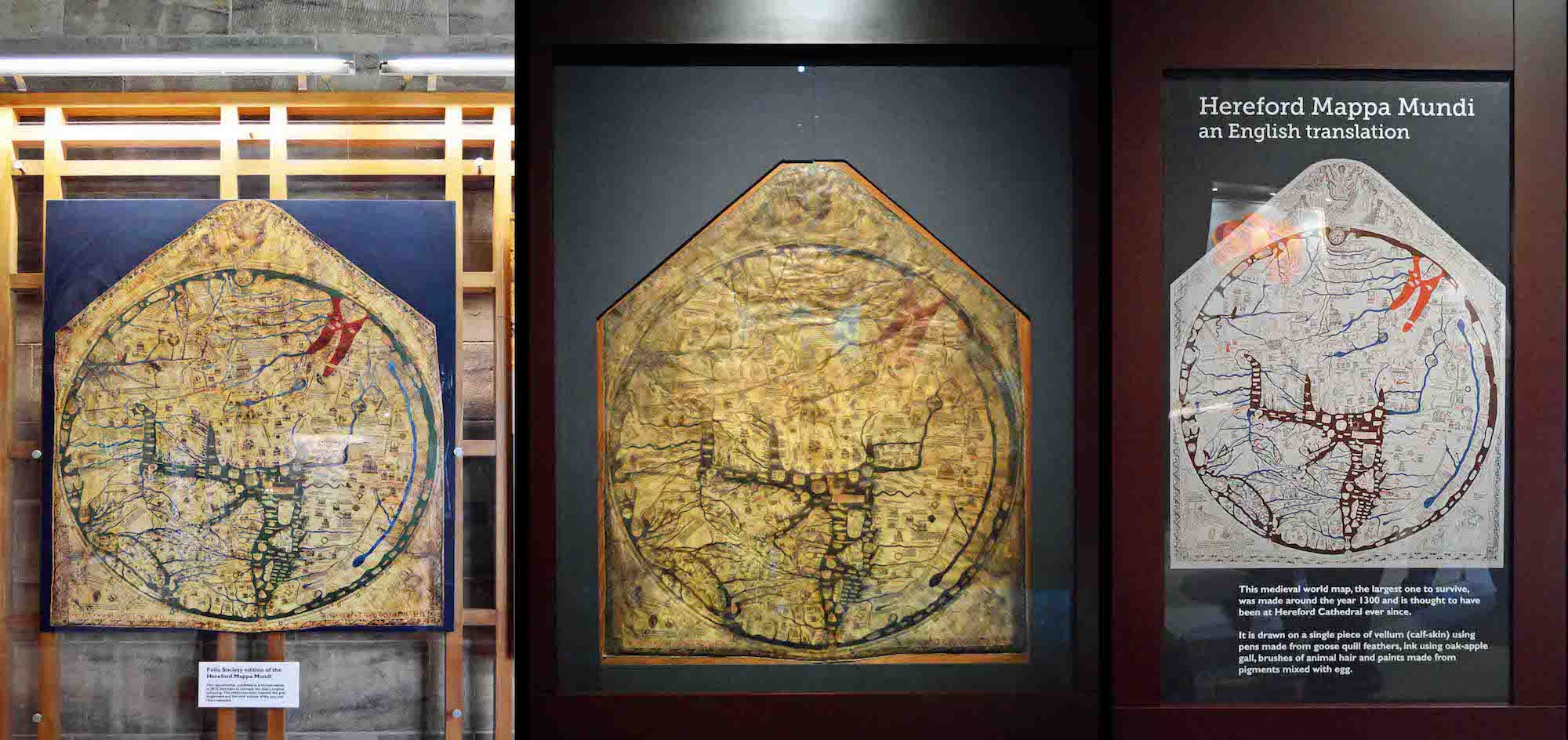

32. MAPPA MUNDI

The Mappa Mundi is housed in Hereford Cathedral and is one of Britain’s finest medieval treasures. Great world maps were an English speciality in the Middle Ages and were drawn on cloth, walls or animal skin. Only the Hereford World Map – Mappa Mundi – has survived complete and is believed to be the world’s largest medieval map. The map is drawn on a single sheet of vellum (calf skin) and measures 64 inches by 52 inches, tapering towards the top. It is generally believed that the map was created in the late 1290s and written in English Gothic script by one person alone. The map is attributed to one ‘Richard of Haldringham or Lafford’ (Holdingham and Sleaford in Lincolnshire) who was also known as Richard de Bello. Whilst the map was drawn in Lincoln, it was almost certainly in Hereford by 1330.

33. MAPPA MUNDI DISPLAYS

There are several other items to be seen in the Mappa Mundi display room: several copies, some information, and a chained book – an enticement to visit the nearby Chained Library.

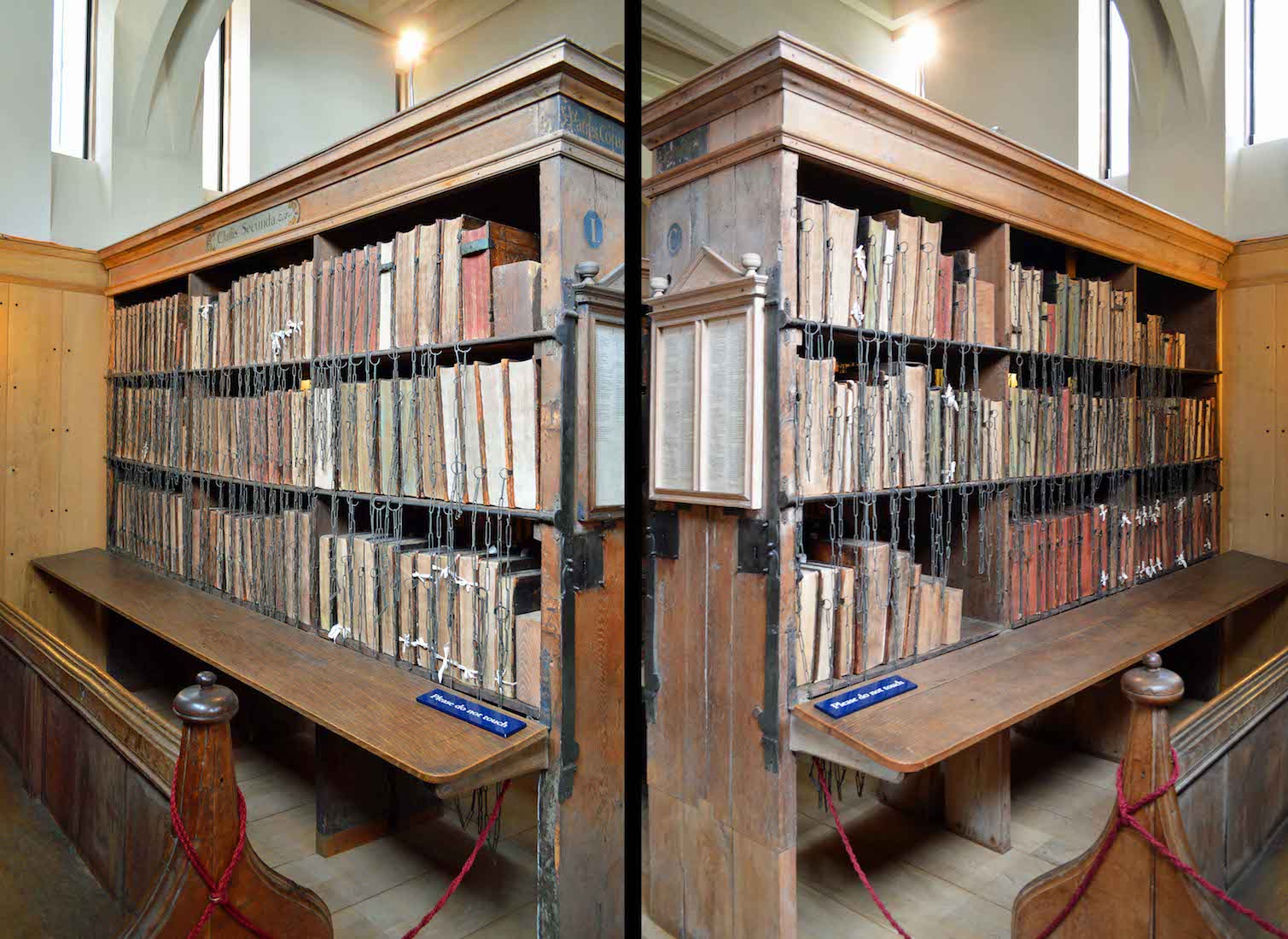

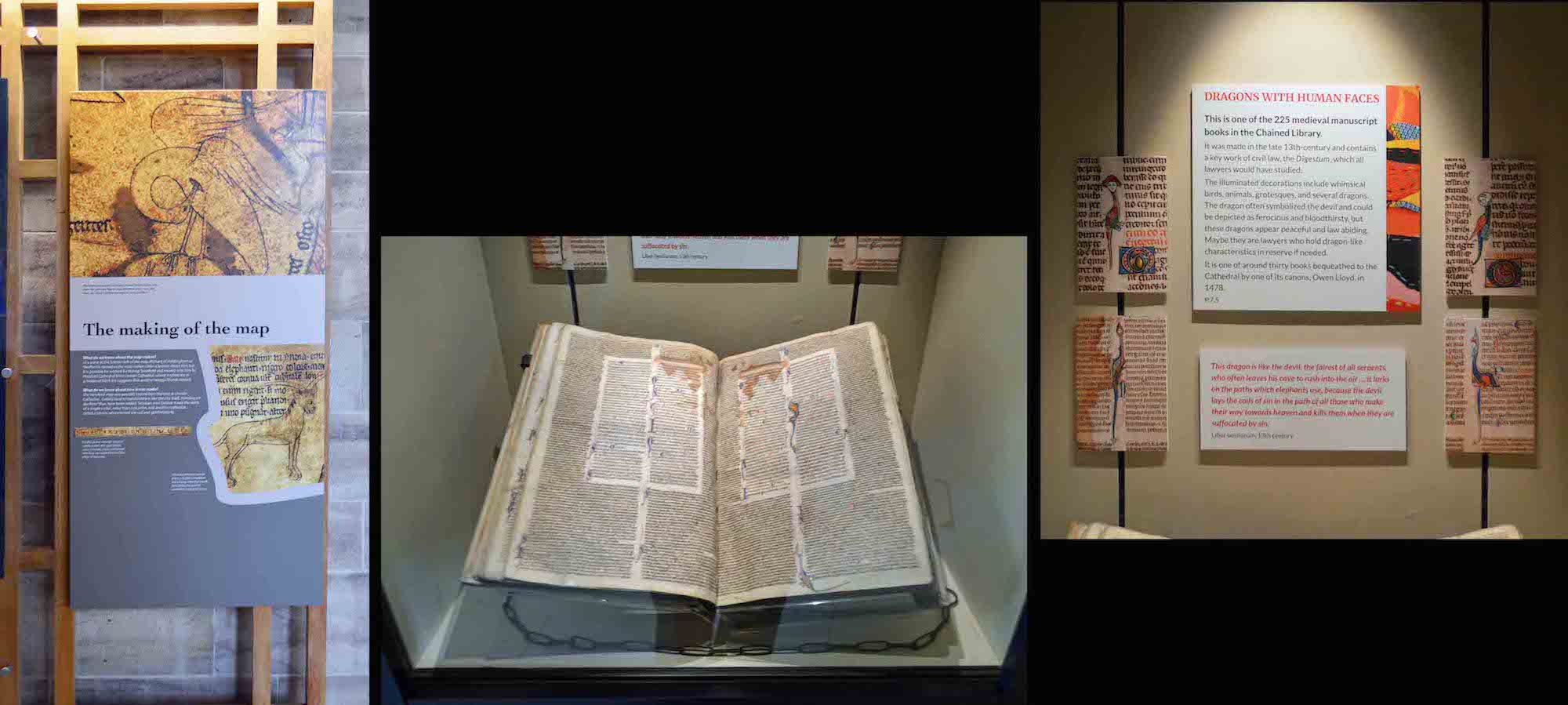

34. CHAINED LIBRARY

The chaining of books was used in European libraries from the Middle Ages to the 18th century, and Hereford Cathedral’s 17th-century Chained Library is the largest to survive with all its chains, rods and locks intact. The cathedral’s earliest and most important book is the 8th-century Hereford Gospels; it is one of 229 medieval manuscripts which now occupy two bays of the Chained Library.

A chain is attached at one end to the front cover of each book; the other end is slotted on to a rod running along the bottom of each shelf. The system allows a book to be taken from the shelf and read at the desk, but not to be removed from the bookcase. The books are shelved with their foredges, rather than their spines, facing the reader (the wrong way round to us); this allows the book to be lifted down and opened without needing to be turned around – thus avoiding tangling the chain.

35. CHAINED LIBRARY DISPLAYS

There are several other exhibits in the Chained Library display room. ••• The specially designed chamber in the New Library Building not only means that the whole library can now be seen in its original arrangement as it was from 1611 to 1841, but also allows the books to be kept in controlled environmental conditions according to modern standards of presentation.

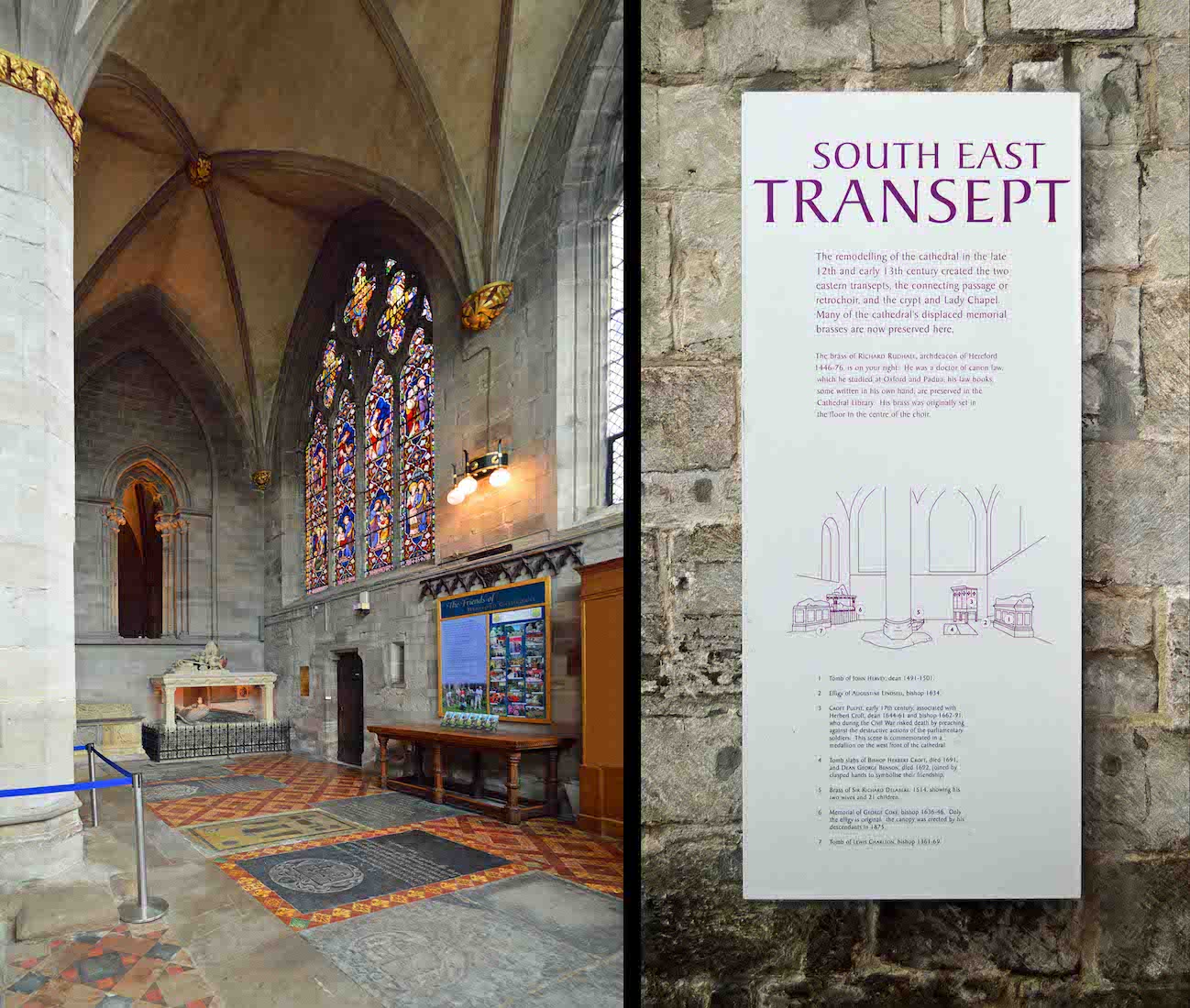

36. SOUTHEAST TRANSEPT

We leave this museum wing with the thought of exploring the main Cathedral, only to find that the funeral is still in progress in the nave. Undeterred, we enter the Southeast transept off the chapter house garden. This part of the Cathedral including the two Eastern transepts, the Lady Chapel and the crypt, date from the late 12th and early 13th centuries. We note in particular the colourful window, the tiled flooring, and the two effigies.

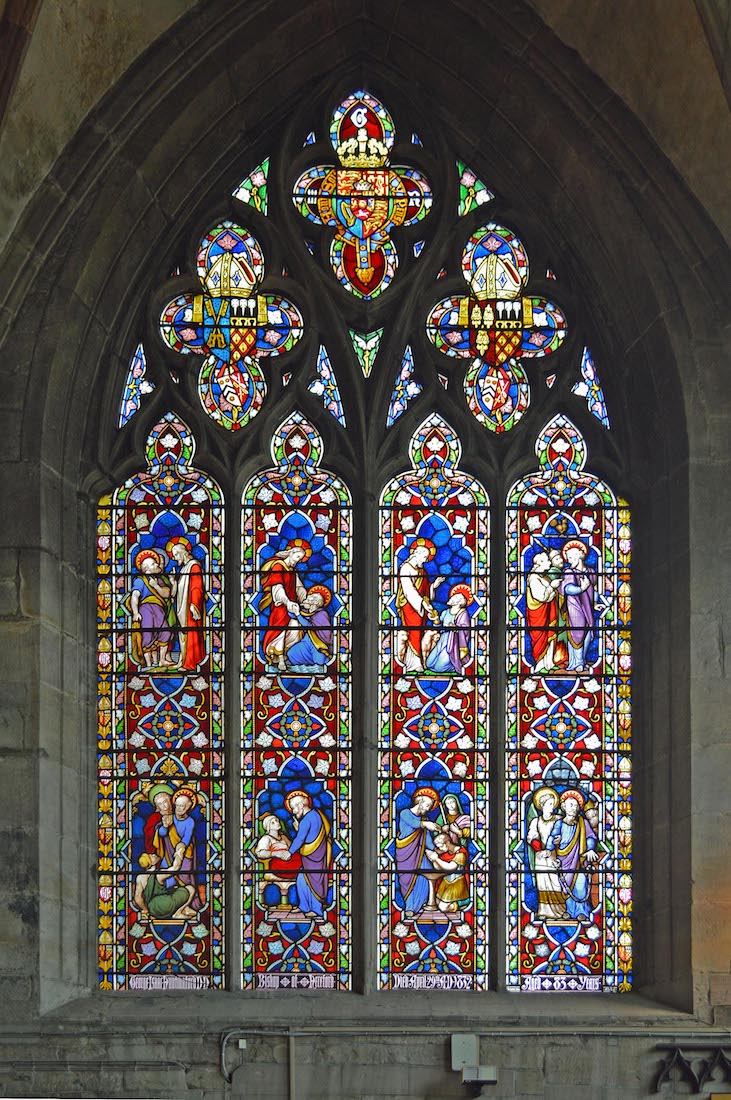

37. TRANSEPT WINDOW

This is a window about Peter. From top left we see: the call of Peter, Jesus rescuing Peter from the sea, Jesus giving Peter the keys of the Kingdom, Peter denying Jesus, Peter baptising the jailer, Peter and John healing a crippled man, Peter raising Tabitha, the angel releasing Peter from prison.

38. TRANSEPT WALL TOMBS

There are two tombs with effigies across the North wall of this transept. The right one is that of George Coke. George Coke (or Cooke) (1570 – 1646) was successively the Bishop of Bristol and Hereford. After the battle of Naseby in 1645, Hereford was taken and Coke was arrested and taken to London. He avoided charges of High Treason in January 1646 and died in Gloucestershire that year.

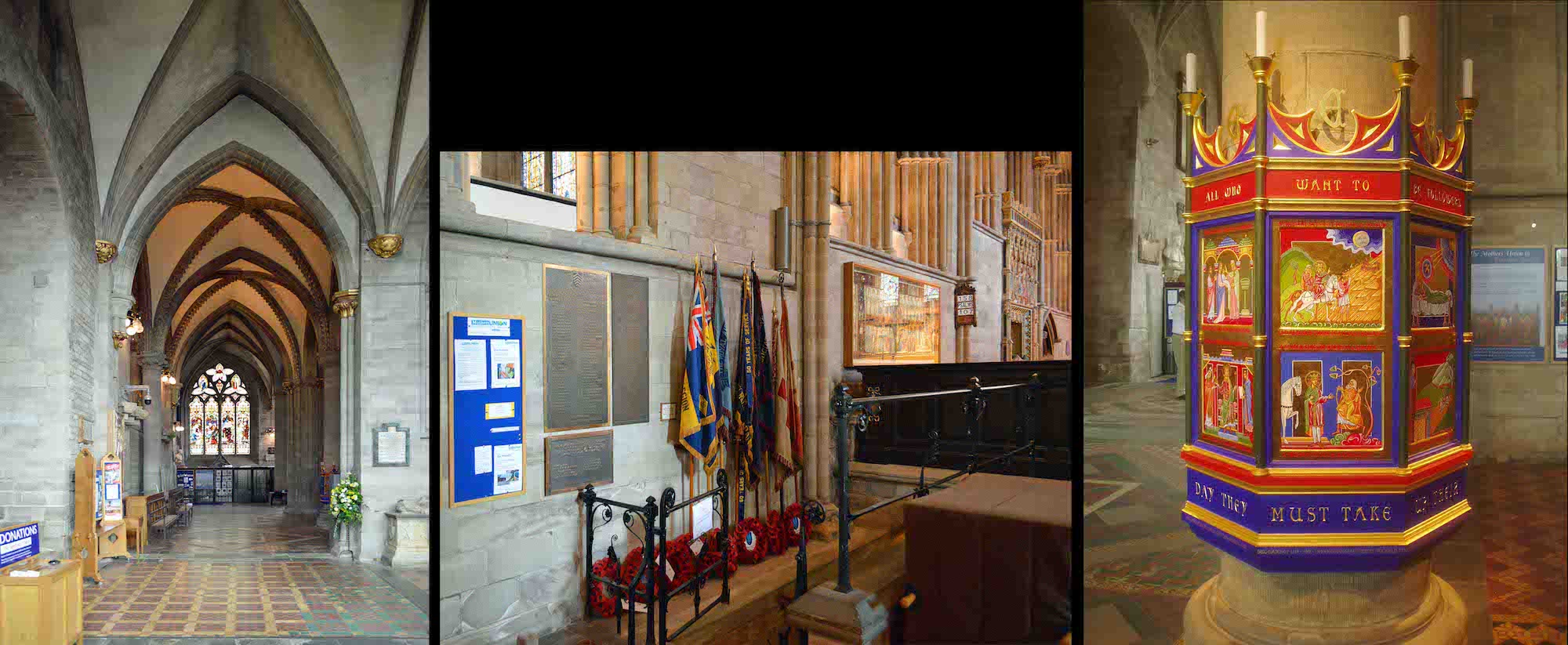

39. RETROCHOIR TO LADY CHAPEL

There is a cross aisle which runs across the Cathedral at this point: it is known as the retrochoir as it runs to the rear of the choir/sanctuary. Looking carefully, we see that halfway across on the right is a brightly coloured – something! A right turn here will take us either to the Lady Chapel, or down some stairs past the memorial colours to the crypt. We see that the vividly coloured column is a new shrine to King Ethelbert, depicting scenes from his life. It replaces the long lost original shrine which was destroyed by the Welsh in 1055. [Right photo credit: Aidan McRae Thomson]

40. LADY CHAPEL

Walking past the shrine, we come to the spacious and beautiful Early English Lady Chapel, which is built over the crypt and approached by an ascent of five steps. There is much to see here, but for the moment we notice the nearest four windows, as well as the altar cloth below the left window and the icon on the wall at right.