CRYPT

CRYPT PLANS

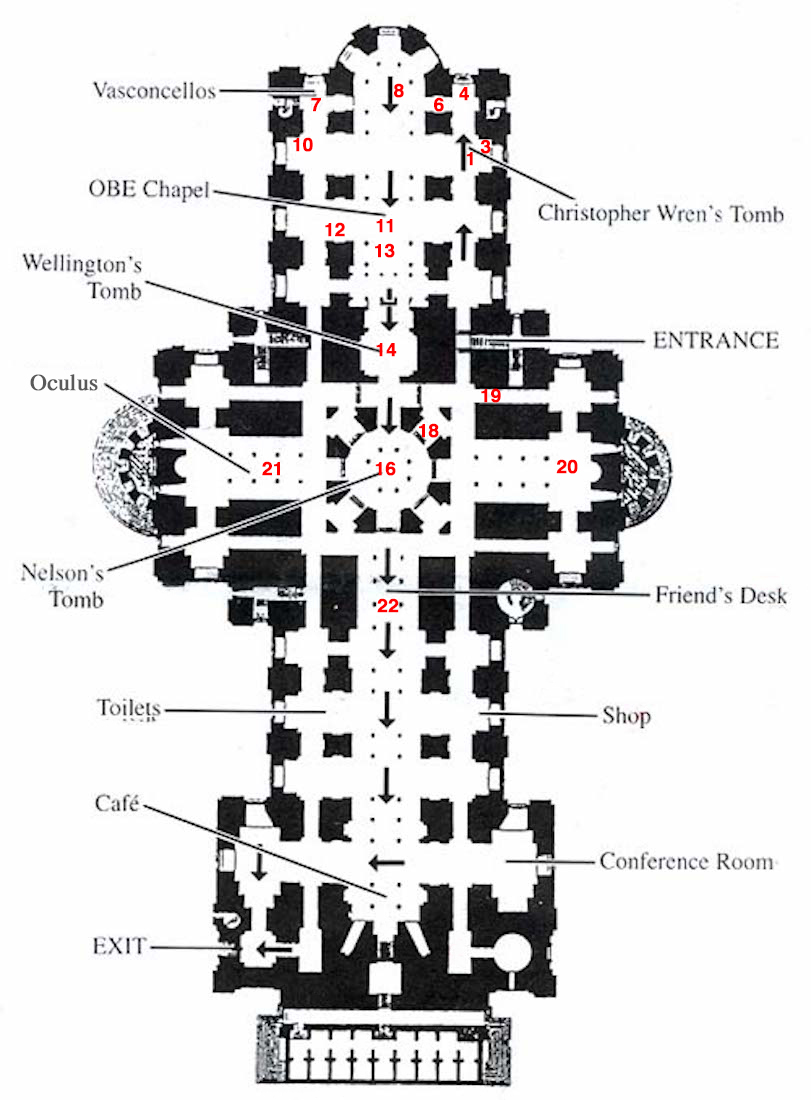

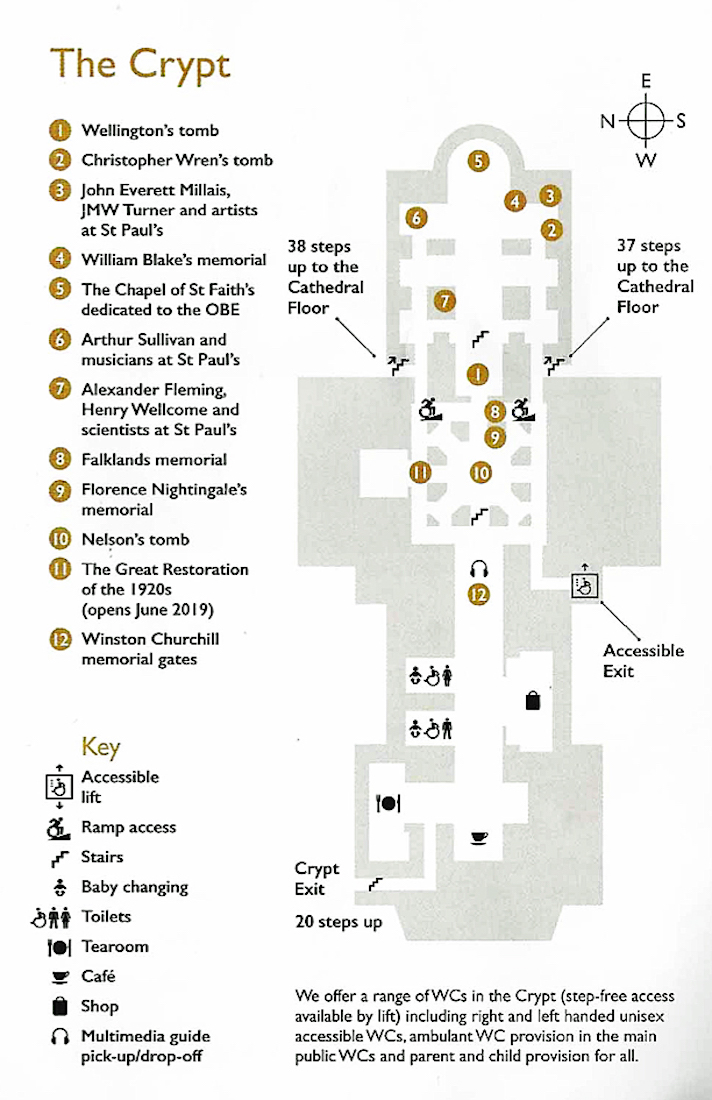

The whole lower level of St Paul’s is called the crypt. We have already investigated the more public West end with the café and the shop. The transepts and East end contain some open chapel spaces, but can appear to be a bewildering maze of aisles and adjoining spaces filled with monuments! The website with this link gives a listing, description and placing of a great many of these monuments, and there is little point in replicating this. So here we shall attempt to walk through the crypt, trying to get a ‘feel’ of the different spaces, and looking in detail at just some of the monuments.

There are two main contributors to this section: Aidan McRae Thomson and Rex Harris. As previously, their photographs will be labelled AMT and RH respectively, with details given in the Conclusion.

Our route for investigating the Crypt is particularly marked out in the first plan above, beginning at the Entrance and with the red numbers indicating successive pages in our exploration. INDEX INDEX

C1. SOUTH AISLE W

From the entrance to the crypt, we turn right to find the tomb of Christopher Wren. This is a view from next to the tomb looking back down the aisle in a Westerly direction. Already there are various monuments on the walls! The nearest bust is of Irish painter James Barry. [Photo Credit: Wikimedia] INDEX

C2. WREN’S TOMB NP

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (1632 –1723) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches in the City of London after the Great Fire in 1666, including what is regarded as his masterpiece, St Paul’s Cathedral, completed in 1710. His tomb has a dark engraved covering slab, and there are two plaques on the wall above. These can be seen here. [Photo Credit: NomadicNiko]

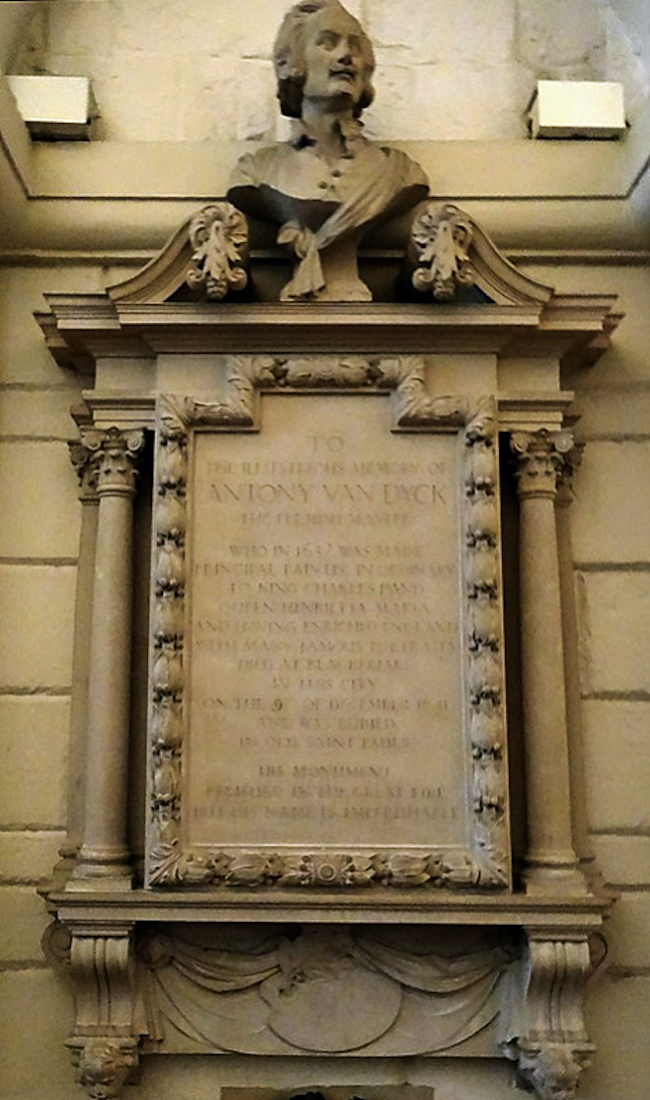

C3. ARTISTS’ CORNER RH

In the same recess as Wren’s tomb is the Artists’ Corner: a place where various artists and painters are remembered. Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599 – 1641) was a Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Southern Netherlands and Italy.

C4. KNIGHTS BACHELOR CHAPEL NP

This little chapel lies at the very Eastern end of the South aisle. The Imperial Society of Knights Bachelor was formed in 1908 in the United Kingdom and received royal recognition in 1912. Its patron is Queen Elizabeth II. It is a registered charity and seeks to uphold and advise on the dignity and rights of Knights Bachelor and knighthood, and to register every duly authenticated knighthood. In 1962, the society established its own chapel in the Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield, London. In 2005, the chapel was moved to St Martin’s Chapel in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral. The Society’s badge may be worn in the form of a brooch by wives and daughters of knights. The painting shows St Martin dividing his cloak to share with a beggar. More about this painting can be found here. [Photo Credit: NomadicNiko] We notice that the Chapel has an unusual window.

C5. CRYPT WINDOWS RH

This is the window of the Knights Bachelor Chapel. The crypt windows at this Eastern end of the crypt have an unusual shape, and are interesting in design. There are five by Brian Thomas dating from 1960 and made by James Powell and Sons. There are a further three of later date by Caroline Benyon. Most of these are depicted here.

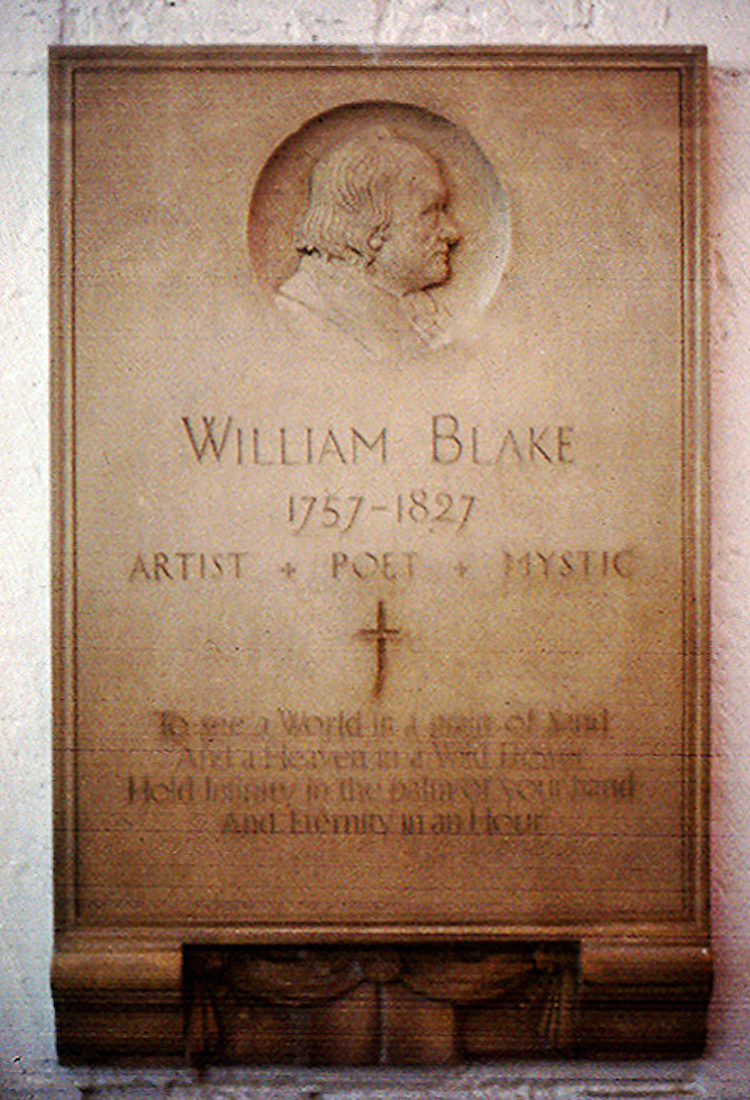

C6. SIR WILLIAM BLAKE AMT

Leaving the Knights Bachelor Chapel, I was surprised to pass this plaque remembering William Blake . I knew a little of his reputation as a poet, but here he is ‘gathered with’ the famous artists! William Blake (1757 – 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. What he called his prophetic works were said by 20th-century critic Northrop Frye to form ‘what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language’. His visual artistry led 21st-century critic Jonathan Jones to proclaim him ‘far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced’. In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. While he lived in London for almost his entire life, he produced a diverse and symbolically rich collection of works, which embraced the imagination as ‘the body of God’ or ‘human existence itself’. A (rather lengthy!) introduction to Blake’s paintings can be found here.

C7. VASCONCELLOS SCULPTURE RH

Our next destination is the OBE Chapel, but first we walk across to the other side where we find this interesting sculpture, Virgin and Child, by Josefina de Vasconcellos, 1957. Josefina Alys Hermes de Vasconcellos (1904 – 2005) was an English sculptor who worked in bronze, stone, wood, lead and perspex. She was at one time the world’s oldest living sculptor. She lived in Cumbria much of her working life. Her most famous work includes Reconciliation (Coventry Cathedral, University of Bradford); Holy Family (Liverpool Cathedral, Gloucester Cathedral); Mary and Child (St. Paul’s Cathedral); and Nativity at St. Martin-in-the-Fields (Trafalgar Square). We now return to the OBE Chapel.

C8. OBE CHAPEL AMT

This is the small but very attractive OBE Chapel. It sits at the East end of the crypt, and is also known as St Faith’s Chapel. The original St Faith’s was a parish church attached to the old Cathedral destroyed in the Great Fire of London. In 1960 this chapel became the spiritual home to the Order of the British Empire. The OBE was instituted by King George V in 1917, initially to recognise the considerable civilian contribution to the war effort during the 1914–18 war. It was a pioneering honour in its day, being the first five-class Order for national distribution, and the first to admit women to membership. • We notice in particular the floor slab in front of the altar platform, and the two side panels in the wrought iron screen in the foreground. Details of these can be seen here. The heraldic display has been limited to banners for the Queen as sovereign, the Duke of Edinburgh as grand master and a few of the royal grand crosses, including Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother.

C9. OUTSIDE THE CHAPEL GATES NP

Just outside the OBE Chapel screens, we find ourselves in the first of several North-South cross-aisles – this one leading to the South to Wren’s tomb. [Photo Credit: NomadicNiko]

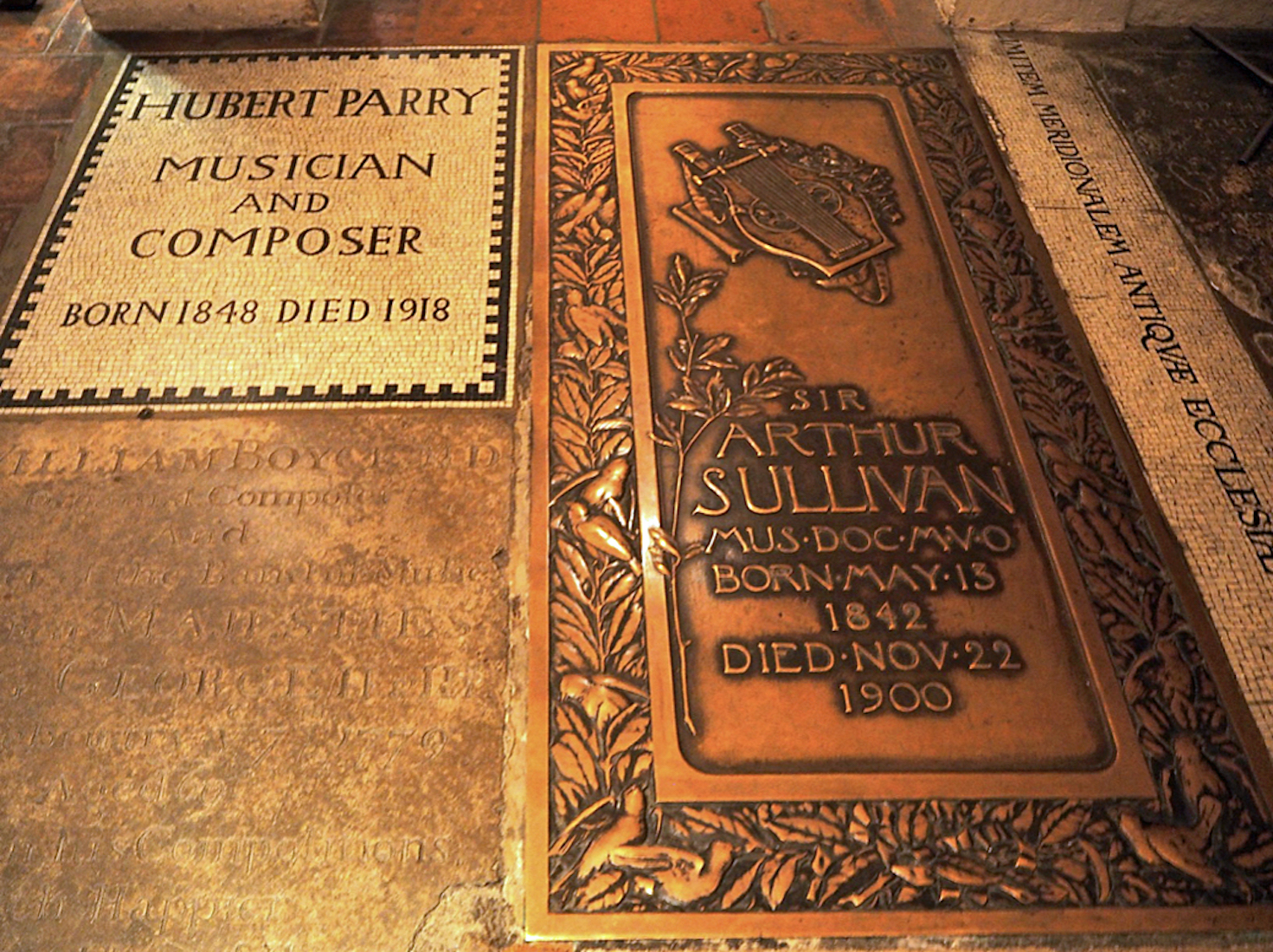

C10. MUSICIANS’ CORNER bb

Following this cross-aisle to the North leads us to the Musicians Corner. Musicians remembered here include Hubert Parry (1848 – 1918) and Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842 – 1900). Less clear here is the memorial to William Boyce (1711 – 1779) who was an English composer and organist. Parry is best known for the choral song ‘Jerusalem’, his 1902 setting for the coronation anthem ‘I was glad’, the choral and orchestral ode ‘Blest Pair of Sirens’, and the hymn tune ‘Repton’, which accompanies the words ‘Dear Lord and Father of Mankind’. Arthur Sullivan is best known for 14 operatic collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ‘H.M.S. Pinafore’, ‘The Pirates of Penzance’ and ‘The Mikado’. His works include 24 operas, 11 major orchestral works, ten choral works and oratorios, two ballets, incidental music to several plays, and numerous church pieces, songs, and piano and chamber pieces. His hymns and songs include ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’ and ‘The Lost Chord’. [Photo Credit: browniebear Requested]

C11. NORTH-SOUTH CROSS AISLE Tr

Moving Westward away from the OBE Chapel, the wide central aisle is filled with fine seating. [Photo Credit: Treske] Beyond, we see the tomb of the Duke of Wellington. But our immediate interest is the second North-South cross-aisle which appears here.

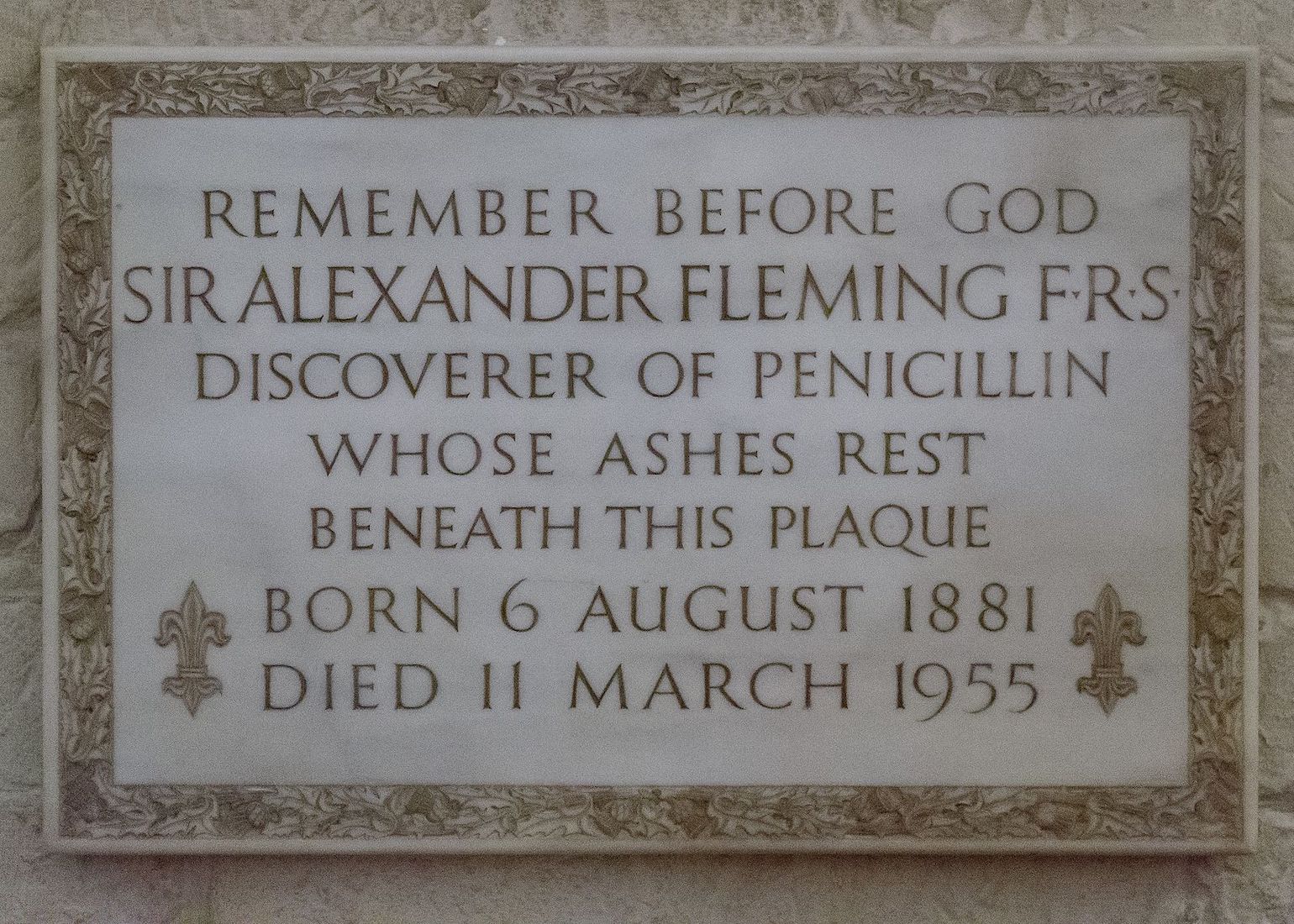

C12. SCIENTISTS’ CORNER W

At the North end of this cross aisle is the Scientists’ Corner containing this monument to Sir Alexander Fleming (1881 – 1995) who discovered penicillin. Fleming was buried in the North aisle here, and there is a small tile with the initials A.F. marking the spot. [Photo Credit: Wikipedia] Next to the plaque is a memorial to Sir Henry Wellcome who was a pharmacist, and patron of medical research.

C13. WEST OF THE OBE CHAPEL IM

A final view, looking towards the OBE Chapel. The large dark memorial at left is a crucifix in memory of John Singer Sargent. [Photo Credit: Iain McLaughlan]

C14. WELLINGTON’S TOMB AMT

Further West, we come to the first of two major tombs in the crypt: the tomb of Arthur Wellesley, the ‘Iron Duke’ of Wellington. After his military achievements, Wellington went on to live a long life,during which he was also Prime Minister, dying at the age of 83. But the passing of the years had not diminished the people’s respect for him and he was afforded a funeral at St Paul’s. The service was a lavish affair. Tens of thousands lined the streets, and stands were erected in the Cathedral that allowed it to fit 13,000 people. The then Dean, Henry Milman, described the sound of the huge congregation reciting the Lord’s Prayer as ‘like the roar of many waters’, a phrase taken from the Book of Revelation. After the service his coffin was lowered into the crypt and buried in a sarcophagus made of luxulyanite granite, just yards from Nelson. His tomb is guarded by four lions – sleeping as there is no need to fight any longer. Several other views of the tomb can be seen here.

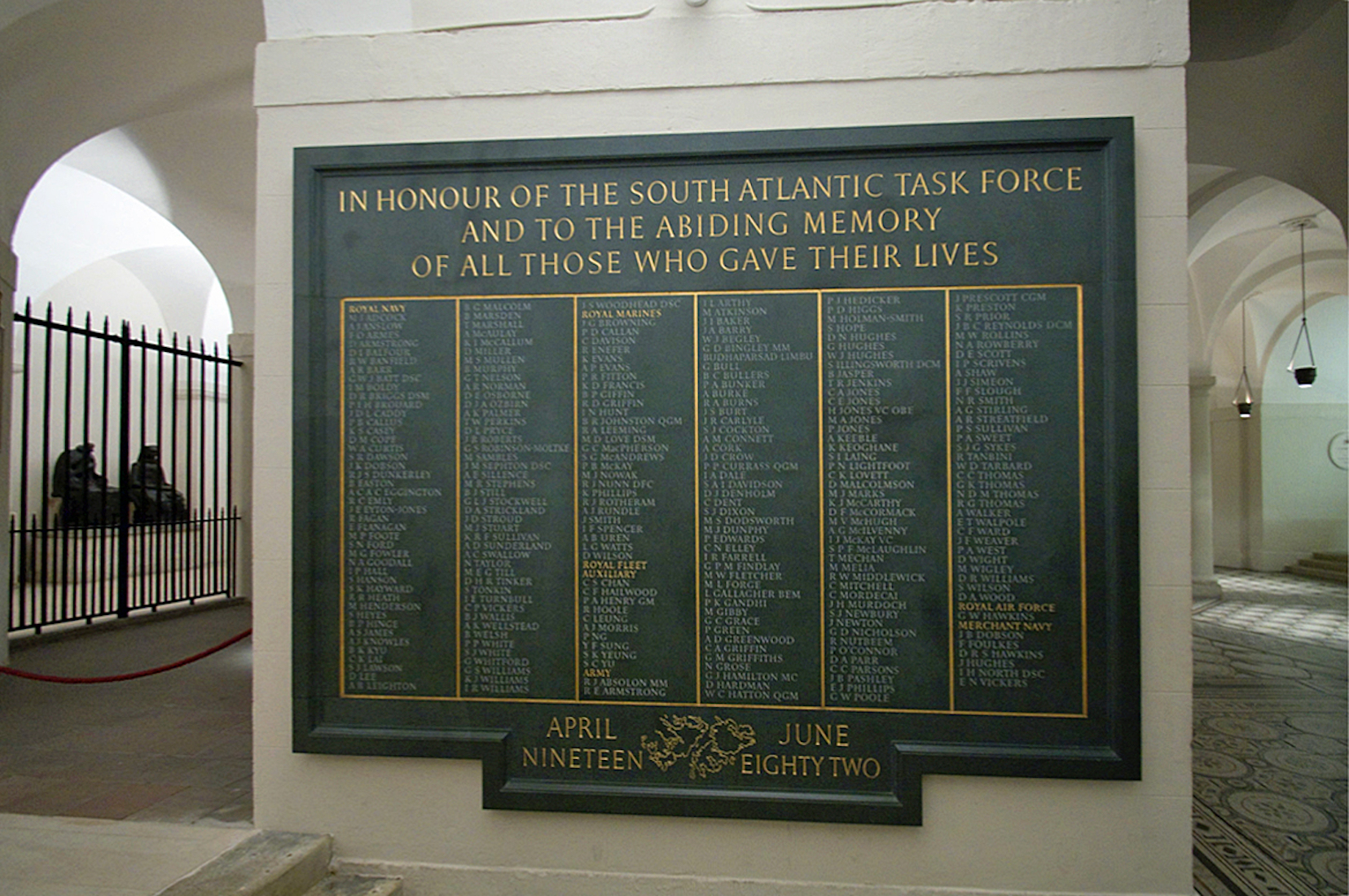

C15. FALKLAND WAR MEMORIAL AMT

Continuing West along the centre aisle we come to this Falklands War Honours Board. The Falklands War was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its territorial dependency, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The conflict began on 2 April, when Argentina invaded and occupied the Falkland Islands, followed by the invasion of South Georgia the next day. On 5 April, the British government dispatched a naval task force to engage the Argentine Navy and Air Force before making an amphibious assault on the islands. The conflict lasted 74 days and ended with an Argentine surrender on 14 June, returning the islands to British control. In total, 649 Argentine military personnel, 255 British military personnel, and three Falkland Islanders died during the hostilities. • The photo shows at left John and Elizabeth Wooley in the South transept: we shall come to them shortly.

C16. NELSON TOMB AMT

The central feature of the crypt is the Nelson Tomb, sitting directly under the dome. Lord Nelson was famously killed in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 and buried in St Paul’s after a state funeral. He was laid in a coffin made from the timber of a French ship he defeated in battle. The black marble sarcophagus that adorns his tomb was originally made for Cardinal Wolsey, Lord Chancellor during the reign of Henry VIII in the early sixteenth century. After Wolsey’s fall from favour, it remained unused at Windsor until a suitable recipient could be found. Nelson’s viscount coronet now tops this handsome monument. The tomb is surrounded by eight bays lined with memorials lying within a square formed by four aisles. It is easy to get lost here(!): views of Nelson’s tomb from different angles are shown here.

C17. CRYPT MOSAIC TILING AMT

The floor of this central area is paved with interesting and colourful mosaic tiling.

C18. NELSON ROTUNDA BAYS RH

We now take some time to investigate the monuments lining the walls of the bays of the Nelson Rotunda. There are a great many memorials here – far too many to make an exhaustive list. These are some that I found interesting. I am interested in the overall emphasis on military personnel, quite overwhelming the number of memorials to those who made great contributions in other areas of life. I wonder what the reason for this is ... .

C19. SOUTH TRANSEPT AMT

Leaving the Nelson Tomb, we turn our attention to the South transept. Here too there is a relatively wide central ‘nave’ with a narrower aisle on either side. The Eastern aisle shown here is of some interest, linking the two transepts across the Eastern side of the Nelson Rotunda. Monuments seen here include: William Napier, and (blackened) John and Elizabeth Wooley at left, with Brian Walton’s tomb, and Admiral Rodney at right. Here are some details.

C20. EAST-WEST AISLE OF SOUTH TRANSEPT AMT

Towards the Southern end of the South transept is this East-West cross-passage. We are looking Eastwards here, towards the reclining effigy of Henry Hart Millman (1791 –1868) who was an English historian and ecclesiastic.

C21. NORTH TRANSEPT AND OCULUS AMT

The North transept of the crypt used to be the location of the Cathedral treasury, which then displayed over 200 items of liturgical plate, lent by churches of the Diocese of London, together with examples of the Cathedral's own plate, and some important vestments. I remember from a long-ago visit, admiring the Queen’s Jubilee Cope here. In 2010, the treasury space was developed into a visual arena where visitors are invited to discover the 1400 year history of St Paul’s as The Nation’s Church. Images are projected directly onto the walls – at times a single picture and at others an impressive 270° projection filling the field of view. Ambient sound as required is directional so as not to leak into the crypt, where Nelson’s tomb is located. Oculus is included within the admission charge for all visitors to the cathedral. A timeline has been installed in the north aisle to introduce the projections. It puts the long span of the site’s history into national and international context. • I would be happy to add photographs of the oculus here ... . The Queen’s Cope and some effigies can be seen here.

C22. TO THE NAVE RH

A short walk from the Nelson Monument in a Westerly direction brings us to these gates which open to the more public area of the crypt encompassing the shop and restaurant. We explored this area in Section XT of this site – you can return to the introductory pages here. Alternatively you can proceed to the next page in which we shall climb to the heights of the dome.